The Criminalization of Dietary Supplement Enforcement

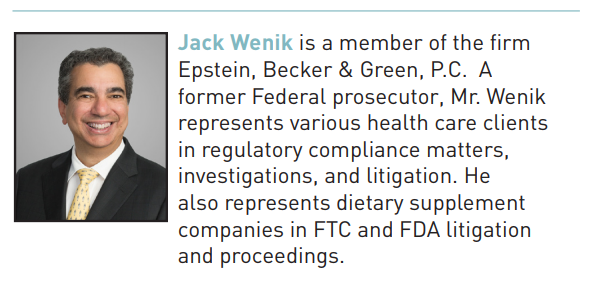

by Jack Wenik

Is dietary supplement enforcement going the way of health care? Those practitioners who represent hospitals, physicians, and other providers have by now grown accustomed to aggressive government enforcement efforts, which have moved well beyond administrative actions or civil False Claims Act litigation. Health care companies, non-profit institutions, clinicians, and other health care providers are now routinely prosecuted by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and/or various United States Attorney’s Offices, many of whom now have units expressly dedicated to “health care fraud.”1 It has become almost an annual ritual in which DOJ bundles together a series of unrelated health care fraud cases and, with much fanfare, announces a “takedown” of defendants as if they were members of organized crime organizations.2

More concerning still is that the line between civil and criminal enforcement has been blurred. Health care institutions routinely face parallel proceedings with civil, regulatory, and criminal exposure. While ethical rules in theory prevent the use of a criminal prosecution to gain advantage in a civil case,3 defense practitioners will relate that the reality is much different. Finally, the government has brought criminal prosecutions in disputes involving clinical judgment alleging unnecessary stent or angioplasty procedures where there is and has been considerable scientific debate.4

We are beginning to see seeds of this aggressive government approach taking root in the world of dietary supplements. The Consumer Protection Branch of DOJ (the unit responsible for dietary supplements) is increasingly bringing criminal prosecutions in matters where, in the past, a civil proceeding would have been commenced on behalf of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Borrowing from the health care playbook, DOJ has bundled together unrelated criminal cases involving dietary supplement companies and announced nation-wide “sweeps” with the attendant publicity accompanying its press release.5

Two recent federal prosecutions, both of which are still pending, illustrate this new aggressive approach by the government, using extensive criminal charges against dietary supplement companies even in areas where the science is controversial. They raise a concern as to the increasing “criminalization” of dietary supplement enforcement by the government.

United States v. USPlabs, LLC, et al.

In United States v. USPlabs, LLC, et al.,6 the government alleges a host of adulteration, misbranding, fraud, and conspiracy charges arising out of the defendants’ sale of certain workout and weight-loss products. Among other things, the superseding indictment alleges that in late 2013 the USPLabs’ product, OxyElite Pro, caused liver toxicity and liver injuries, including liver transplants.7 These allegations appear to be the impetus for many of the criminal charges that follow.

Of course, no one would disagree that FDA should take action when a party is engaged in the sale of adulterated products that may be life threatening. The agency has numerous tools at its disposal for these instances including injunctions, seizures, administrative detentions, and other measures. However, these enforcement actions are distinct from criminal prosecution years after the events in question.8

Indeed, such was the case with OxyElite Pro. A series of illnesses in Hawaii prompted FDA to send a warning letter about OxyElite Pro in late 2013. However, subsequent to the issuance of the warning letter, considerable debate arose within the scientific community as to whether OxyElite Pro, or any other dietary supplement, was associated with the liver issues reported in 2013. For example, in an article published in the journal Annals of Hepatology, the authors concluded that “[T]he Hawaii liver disease cluster is now best explained by various liver diseases rather than any [dietary supplement] or [OxyElite Pro].”9 Nevertheless, the government is pursuing criminal charges related to these circumstances.

As a civil matter, it might be appropriate for the government to take action against a dietary supplement company’s marketing of a product that has had questions raised as to its safety. However, it is a different matter entirely, to bring a criminal prosecution. Pursuant to the United States Attorney’s Manual, a prosecution should only be brought when the “government believes that the admissible evidence is sufficient to obtain and sustain a guilty verdict by an unbiased trier of fact…”10 When an issue is subject to legitimate scientific debate, the initiation of a criminal prosecution is questionable, at best.

United States v. Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals, et al.

In United States v. Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals, et al.,11 the government alleges, among other things, misbranding, conspiracy and fraud charges against the defendants arising out of the sale of several products. Of particular interest is the government’s allegation that the defendants’ sale of the dietary supplement Choledrene was illegal because it did not list Lovastatin, an FDA-approved drug, as an ingredient on its label.

As the defendants pointed out in a motion to dismiss, the active ingredient in Choledrene was manascus purpureus, more commonly known as red yeast rice.12 Red yeast rice naturally contains monacolin K, a cholesterol lowering statin identical to Lovastatin. Red yeast rice products have been widely sold for years both online and at mainstream mass retailers. A Harvard researcher recently published an article analyzing the amount of monacolin K in 26 different brands of red yeast rice products, none of which listed Lovastatin on their labels.13 Years earlier, civil action by FDA against a similar product, Cholestin, produced conflicting district court and appellate decisions as to how red yeast rice products should be classified, with the issue turning on how the products in question were marketed.14

While there may be legitimate reasons why FDA would want to regulate red yeast rice products, and there are certainly a wide array of administrative tools to insure the quality and safety of such products, and how they should be labeled and marketed, a criminal prosecution regarding the labeling of them is simply unprecedented. There is no reason to believe that Choledrene has any unique attribute making it less safe or suitable for sale to the public than the dozens of other brands of red yeast products with which it competed, many of which had vastly higher levels of monacolin K. The aggressive use of a criminal charge for this conduct is concerning.

Implications for the Dietary Supplement Industry

It would be a mistake to dismiss the government’s aggressive use of criminal charges against dietary supplement makers as limited to a small array of outlier companies. Again drawing a parallel to what occurred in health care, what began as targeted efforts against select providers, has expanded to the point where some of the nation’s most prestigious teaching hospitals operate under corporate integrity or non-prosecution agreements, and publicly traded health care companies and their executives are routinely targeted in criminal investigations.

Given the substantial growth of the dietary supplement industry, the participation in this market space by mainstream publicly traded companies, and the sensitive nature of these products as affecting the public’s health, we can expect increased scrutiny by the government, including the continued use of criminal investigations/prosecutions—even in areas subject to scientific debate. Savvy industry players will take preventive measures to protect themselves. In this regard, they should mimic what many providers do in health care: establishing extensive compliance programs, hiring a competent compliance officer, purchasing investigation insurance from commercial carriers, and conducting compliance/regulatory training for board members and key management, will

ultimately pay dividends. The government is raising the stakes for dietary supplement companies and the industry needs to respond in kind.

Update Magazine

December 2018/January 2019

- See, for example, U.S. Department of Justice, Criminal Division, Fraud Section’s Health Care Fraud Unit, which is composed of 55 prosecutors focused on health care fraud-related cases, https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/health-care-fraud-unit.

- In a June 28, 2018 Press Release, the Department of Justice announced its “Takedown” with charges against 601 defendants, including 76 doctors. See https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/national-health-care-fraud-takedown-results-charges-against-601-individuals-responsible-over.

- See, e.g., New Jersey Rule of Professional Conduct 3.4(g).

- See, e.g., United States v. Chhibber, 741 F.3d 852 (7th Cir. 2014); United States v. McLean, 715 F.3d 129 (4th Cir. 2013); and United

States v. Patel, 485 F. App’x 702 (5th Cir. 2012). - See, for example, the Department of Justice’s November 17, 2015 Press Release trumpeting the round-up of 100 dietary supplement companies in both criminal and civil actions. See https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-and-federal-partners-announce-enforcement-actions-dietary-supplement-cases.

- United States v. USPlabs, LLC, et al., 3:15-cr-00496-L (N.D. Tx.), Doc. 95, January 5, 2016.

- Id. at ¶¶ 31-35.

- The initial USPLabs indictment was filed on November 4, 2015, two years or more after many of the underlying events.

- Teschke, et. al, The mystery of the Hawaii liver disease cluster in summer 2013: A pragmatic and clinical approach to solve the problem, 15 Annals of Hepatology 2016:91-118.

- United States Attorney’s Manual, Section 9-27.220.

- United States v. Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals, et al., 1:17-cr-00229-AT-CMS (N.D. Ga.), Doc. 7 September 28, 2017.

- Defendants Motion to Dismiss, 1:17-cr-00229-AT-CMS, Doc. 193, September 28, 2018.

- P. Cohen, et. al, Variability in strength of red yeast rice supplements purchased from mainstream retailers, 24 European Journal of Preventive Cardiology at 1431-1434 (2017).

- See, Pharmanex v. Shalala, 221 F.3d 1151 (10th Cir. 2000).