2022 Year in Review—Top 10 Food and Agribusiness Regulatory and Legal Issues in Canada

By Eileen McMahon, Yolande Dufresne, Melanie Sharman Rowand & Jacquelyn Smalley

2022 brought many changes to Canada’s food and agribusiness regulatory space, and 2023 is shaping up to be another eventful year. Below is our list of the top 10 food and agribusiness regulatory and legal issues in Canada from 2022 and the first quarter of 2023.

1. Labeling Changes Ahead for Prepackaged Foods High in Saturated Fat, Sugars, and Sodium

After years of consultations and research activities by Health Canada, the Canadian government amended the Food and Drug Regulations (FDR) in July 2022 to introduce new front-of-package (FOP) nutrition labeling requirements to help Canadians identify products that are high in certain nutrients of public health concern, namely saturated fat, sugars, and sodium (FOP Labeling Changes).[1] As a result, Canada has become one of only a small group of countries with a mandatory FOP labeling regime for foods high in nutrients of concern. Notably, there is currently no equivalent requirement in the United States at the time of writing.[2]

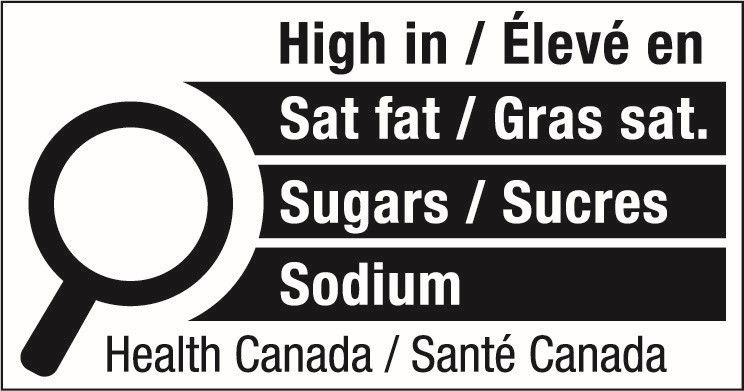

The FOP Labeling Changes require that an FOP nutrition symbol (an example of which is shown below) be displayed on prepackaged foods, including beverage products, that contain saturated fat, sugars, and/or sodium at levels that meet or exceed a specific threshold. For most prepackaged foods, this threshold is 15% of the designated daily value for the nutrient; however, certain categories of foods have a higher or lower prescribed threshold. The FDR amendments outline specific requirements regarding where an FOP nutrition symbol must appear on packaging, as well as the format, size, visibility, language, and orientation of the symbol.

Certain categories of prepackaged foods have been exempted from the requirement to display the FOP nutrition symbol for technical, nutritional/health-related, or practical reasons (e.g., sugar, honey, maple syrup, salt, and butter are exempted because displaying an FOP nutrition symbol would be redundant on such products). Other products, including those meant to fulfill the nutritional needs of vulnerable groups (e.g., infants or persons requiring oral or tube feeding due to an injury or medical condition), are prohibited from displaying an FOP nutrition symbol. The FOP Labeling Changes also introduce restrictions on the use of certain nutrient-content and health-related claims when the label of a prepackaged food product contains an FOP nutrition symbol because such claims could be misleading.

In accordance with the joint food labeling coordination policy from Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA),[3] all prepackaged food products are expected to be compliant with the new requirements as of January 1, 2026. However, products imported into or manufactured in Canada or packaged at retail before January 1, 2026 that are not compliant with the new requirements can continue to be sold after this date.[4]

Companies in the food and beverage industry should review the new FOP labeling requirements closely and plan to make packaging, product, and operational changes. For example, some companies may consider reformulating products to reduce the amount of saturated fat, sugars, or sodium below the designated FOP thresholds when relabeling for FOP nutrition symbols may not be feasible.

2. Gene-edited Plants Get Lighter Regulatory Touch in New Health Canada Guidance for Novel Foods

Health Canada has signaled a favorable regulatory environment for foods derived from gene-edited plants in new guidance on novel foods.[5] Pursuant to Canadian law, foods that meet the definition of a “novel food” require pre-market notification and assessment by Health Canada. New guidance was developed by Health Canada to clarify the interpretation of the definition of a “novel food” under Canada’s Novel Food Regulations[6] and to address gaps in the guidelines regarding newer technologies, such as gene editing. Although the new guidance does not have the force of law, it does indicate how Health Canada interprets and applies the definition of “novel food” under the Novel Food Regulations.

According to the new guidance, foods derived from genetically modified plants (including gene-edited plants)[7] do not meet the definition of a “novel food” and will not require a pre-market notification and assessment unless the genetic modification results in the presence of foreign DNA in the final plant product or alters specified characteristics in the final plant product—such as the introduction of a known allergen or toxin, changes to key nutritional composition, or changes in the food use of the plant. Of specific importance for gene-edited plants, DNA encoding machinery (e.g., CRISPR Cas protein and associated guide RNAs) is considered to be foreign DNA but will only trigger the Novel Food Regulations if such DNA is not bred out of the final product. As a result, it is expected that many foods derived from gene-edited plants will not require pre-market notification and assessment under the novel food regime. Since the introduction of the new guidance in July 2022, at least two gene-edited plants have been identified as “non-novel products of plant breeding for food use,”[8] which means that they do not meet the definition of a “novel food” and do not require pre-market notification and assessment. According to the new guidance, an expedited review process is available for pre-market assessment of novel foods derived from genetically modified plants that have been transformed with the same DNA sequence as a previously assessed genetically modified plant (referred to as “retransformants”).

While the new guidance is limited to foods derived from plants, Health Canada has signaled an intent to develop similar guidance for novel foods derived from genetically modified animals and microorganisms.[9]

Health Canada has also published a notice of intent to propose amendments to the Novel Food Regulations that are consistent with the interpretation of a “novel food” provided in the new guidance.[10] There is currently no projected timing for the proposed amendments; however, there will be an opportunity for stakeholders to comment once the proposed amendments are published. In the meantime, the new guidance signals that Health Canada is taking a lighter regulatory approach to foods derived from gene-edited plants.[11]

3. End of Transition Period for Amended Fertilizers Regulations

Fertilizers and supplements that are manufactured, imported, and/or sold in Canada are regulated under the Fertilizers Act and Fertilizers Regulations by the CFIA. The Fertilizers Regulations were significantly amended in the fall of 2020 as part of an effort to modernize the regulation of fertilizers.[12] Among the amendments were changes made to the exemptions from registration of certain fertilizer products to better align pre-market regulatory oversight with the risk profile of the products. More specifically, pursuant to the amendments, certain low-risk fertilizers and supplements are subject to reduced regulatory scrutiny under the revised regulations, while products with higher or unknown risks are subject to registration under the revised regulations (even if previously exempted under the former regulations).

To provide regulated parties with time to exhaust their existing inventory and seek registration where necessary, the amendments contain transitional provisions to allow regulated parties to comply with either the revised regulations or the former regulations for a period of three years—i.e., until October 26, 2023. During this transitional period, manufacturers can choose to comply with the revised regulations or the former regulations but cannot combine provisions from the revised and former regulations.[13]

With the deadline to comply with the amended Fertilizers Regulations fast approaching, regulated parties should now be completing their transition steps.

4. Competition Bureau Tackles “Greenwashing”

In early 2022, Canada’s Competition Bureau published a news release advising Canadian consumers that a growing demand for “green” products and services has led to an increase in false, misleading, or unsupported environmental claims, also known as “greenwashing.”[14] This is a topic of interest for food and agribusiness companies, where environmental concerns are at the forefront of many consumers’ minds and where marketing campaigns increasingly seek to make environmental claims. This news release came on the heels of a large settlement between the Competition Bureau and a manufacturer of single-use coffee pods after the Competition Bureau concluded the company’s claims regarding the recyclability of, and the steps involved to recycle, its single-use coffee pods were false and misleading.[15] As part of the settlement, the manufacturer agreed to, among other things, pay a $3 million penalty, change its product packaging, and broadly publish corrective notices.

While greenwashing has been on the Competition Bureau’s radar for several years, 2022’s coffee pod settlement provides an important reminder of the hefty consequences of greenwashing for businesses using, or intending to use, ads, slogans, logos, and packaging that highlight, in a misleading manner, the environmental attributes or benefits of products sold in Canada. The Competition Bureau advises that vague claims, such as “eco-friendly” and “safe for the environment,” should be avoided as they can have multiple interpretations and lead to misunderstanding and deception. Rather, claims must be specific and precise about the environmental benefits of a product and must be substantiated and verifiable, among other requirements.

5. Health Canada Formalizes Approach to “Treated Articles” under the Pest Control Products Act (PCPA)

Amendments to Canada’s Pest Control Products Regulations (PCPR) were published on December 7, 2022,[16] which codify the regulation of “treated articles” by Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA). These specific amendments will come into effect on June 7, 2023, and while food products are exempt, many agribusiness products could be affected.

Specifically, the amended regulations define “treated articles” as a class of regulated products that comprise 1) any non-food inanimate product or substance, 2) treated with a pest control product during manufacturing by (a) incorporating the pest control product into the article, or (b) applying the pest control product to the article, and whereby 3) the product’s primary purpose before the treatment was not pest control (i.e., the product alone was not a pest control product).

Once these amendments become law, non-food products that are treated with a pest control product will be subject to regulation and registration under the PCPR as a “treated article,” unless otherwise exempted. Manufacturers and importers should therefore review product lines in light of these pending changes, because “treated articles” extend beyond the types of products typically thought of as pest control products such as pesticides for farming or insect repellents. Rather, “treated articles” may include non-food products that have had antimicrobial agents applied to them during the manufacturing process.

There are a number of exemptions under the legislation that exempt products entirely from the PCPA framework or that exempt products from registration with the PMRA. For example, if the treated article is treated with an antimicrobial preservative and is a drug, cosmetic, or class II–V medical device regulated under the Food and Drugs Act, feed regulated under the Feeds Act, or fertilizer or supplement regulated under the Fertilizers Act, the product will be exempt from compliance with the PCPA/PCPR.[17]

Further, a treated article will not need to be registered with the PMRA if: 1) it has only been treated with an antimicrobial preservative (and no other pest control product), 2) the sole purpose of the treatment is to preserve or protect the article, and 3) the preservative used is registered or otherwise authorized or recognized by the PMRA.[18]

As the PCPA and PCPR already include several exemptions and caveats, with new exemptions being added as part of these amendments, the analysis will be very fact specific.

6. New Framework for Supplemented Foods

A new regulatory framework for prepackaged foods with added vitamins, minerals, amino acids, or other ingredients, such as caffeinated energy drinks and granola bars with added vitamins (Supplemented Foods), came into force on July 21, 2022.[19]

Previously, Supplemented Foods required a temporary marketing authorization (TMA) from Health Canada before they could be sold in Canada. However, under the new framework, a Supplemented Food can now be sold in Canada without the need to seek pre-market authorization from Health Canada if, subject to certain exceptions, the product falls within a permitted food category[20] and contains permitted supplemental ingredients[21] according to the conditions of use prescribed by Health Canada (such as the maximum amount of supplemental ingredient per serving, the specific categories of food to which the supplemental ingredient may be added, required cautionary statements, etc.).

Notably, certain prepackaged foods with added nutrients are not considered Supplemented Foods and are exempted from this new framework, such as foods already permitted to contain added nutrients under the FDR for fortification purposes and foods for special dietary use, subject to certain exceptions.

While the FDR’s existing labeling and advertising requirements for prepackaged foods generally continue to apply to Supplemented Foods, new heightened labeling and advertising requirements now also apply to Supplemented Foods to help consumers identify associated risks and make informed decisions.[22] For example, subject to certain exceptions, a Supplemented Food is required to carry a supplemented foods fact table that provides additional information about supplemental ingredients in the product. Additionally, Supplemented Foods containing certain supplemental ingredients, or amounts of supplemental ingredients that meet or exceed specified thresholds, must display cautionary statements, as well as a “Supplemented Food Caution Identifier” (i.e., a prescribed symbol) on the principal display panel.

Supplemented Foods sold in Canada as a result of a TMA that was either approved or applied for before July 21, 2022 have until January 1, 2026 to comply with the new framework, subject to certain conditions.

Going forward, manufacturers can submit a request to Health Canada to add, or revise the conditions of use of, a permitted supplemental ingredient or supplemented food category.

7. Formal Review of Canada’s Cannabis Act Underway

Nearly four years after Canada’s federal Cannabis Act first came into force, the Minister of Health announced a legislative review of the statute on September 22, 2022. This review is intended to assess whether the current legislative framework is meeting its objectives, including deterring criminal activity, displacing the illicit cannabis market, and providing adults access to legal cannabis products.

The federal Cannabis Act came into force on October 17, 2018, legalizing the production, sale, and use of recreational cannabis across Canada. At the time it came into force, the Act included a built-in review process requiring Canada’s Minister of Health to initiate a review of the Act within three years. The legislation requires the review to consider the impact of the legislation on public health, consumption habits of young persons with respect to cannabis use, the impact of cannabis on Indigenous persons and communities, and the impact of the cultivation of cannabis plants in personal homes.[23]

Likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the review was delayed. As part of the review announced in 2022, Health Canada solicited input from industry and the public in the fall of 2022, to be considered in the review report ultimately provided to Parliament. Pursuant to the Cannabis Act, the independent panel’s report must be brought before Parliament no later than 18 months after the review commences.

8. Alternative Proteins on the Front Burner

With exploding interest in alternative proteins, plant-based foods are seeing rapid development. In 2023, the CFIA intends to publish final guidelines for “simulated” meat and poultry products, following extensive consultation with various stakeholders.[24] The FDR provides strict labeling, composition, and fortification requirements for “simulated” meat and poultry products (defined as products that do not contain meat, poultry, or fish but that have the “appearance” of a meat or poultry product).[25] While the regulatory requirements for “simulated” meat and poultry products will not change, the final guidelines are intended to provide direction for determining whether a plant-based food product is a “simulated” meat or poultry product (and thus subject to heightened requirements for simulated meat and poultry products), or whether it is unstandardized food (and thus subject to the general regulatory requirements for unstandardized foods).

In particular, the final guidelines are expected to interpret the word “appearance” in the FDR definition of “simulated” meat and poultry products based on the overall impression of the product, including the sensory characteristics of the food (e.g., visual appearance, texture, flavor, and odor) and how the food is advertised and represented (e.g., if the food is labeled, advertised, or marketed as a food comparable to a meat product or poultry product). For example, a plant-based food that is manufactured to have the appearance of a beef burger (with simulated bleeding or marbling) would be classified as a “simulated” meat product, whereas a tofu patty that does not resemble a meat or poultry product and is not advertised or represented as being comparable to a meat or poultry product would not. The final guidelines are expected to provide examples of representations that are acceptable for plant-based food products without triggering the “simulated” meat and poultry regulations (e.g., “veggie burger” and “soy patty”), provided that the products are not otherwise represented or marketed as having the appearance of a meat or poultry product. Parties selling plant-based foods in Canada may wish to review the guidelines to understand how their products will be classified and to assess what, if any, labeling changes are needed to avoid unintentionally triggering the “simulated” meat and poultry regulations.

9. Feeds Regulations to Get Major Overhaul

The CFIA is expected to publish amendments to the Feeds Regulations in the fall of 2023. These will be the first major updates to the Feeds Regulations since 1983. These regulations govern the nutritional requirements, manufacture, sale, and import of substances for use in consumption by livestock, including cattle, sheep, swine, and poultry. Proposed amendments were published in 2021 for public consultation, with follow-up consultations in early 2023.

The proposed amendments are intended to modernize the regulatory framework to improve feed safety, reflect international standards, and keep pace with industry innovation.[26] In particular, the proposed amendments are less prescriptive and more focused on safety outcomes through hazard identification and analysis, preventative control plans (PCPs), traceability, record-keeping, and licensing requirements.[27] The proposed regulations include more flexible labeling requirements and incorporate by reference a table of permissible claims and a table of optional nutrient guarantees that can be used on feed labels without product registration when certain conditions are met. Some provisions are expected to come into force as soon as the final amendments are published, while others (such as PCPs, traceability requirements, and licensing requirements) will have a 12 to 18-month transitional period.[28] At the time of writing, the proposed amendments are still in draft form and subject to change.

10. Québec Raises the Stakes with New French Language Requirements[29]

In May 2022, the province of Québec adopted Bill 96,[30] resulting in the most significant amendments to Québec’s Charter of the French Language (French Charter)[31] since the French Charter was adopted in 1977. While Bill 96 introduced new French language requirements in all areas of Québec’s society, food and agribusiness manufacturers operating in Québec should be particularly mindful of the new requirements regarding the use of French language and trademarks on products, signage, advertising, and related materials.

In particular, as of June 1, 2022, product packaging and labeling, catalogues, brochures, order forms, invoices, receipts, and other similar documents provided in Québec in other languages cannot be provided on more favorable terms than the version provided in French.

Further, Bill 96 requires that, as of June 1, 2025, in the province of Québec:

- Only registered trademarks can appear in a language other than French on products and signage and only as long as no corresponding French version of the trademark appears on Canada’s trademark register (which may include applied-for marks, in addition to registered marks). In contrast, before the adoption of Bill 96, trademarks “recognized” under the Trademarks Act (i.e., common law, applied-for trademarks, and registered trademarks) could appear exclusively in a language other than French if a French version of the trademark had not been registered.

- Trademark owners will no longer be able to rely on the inclusion of generic or descriptive English text in a registered trademark in order to avoid translating text into French on a product sold in Québec. If a registered trademark appearing on a product includes a generic term or description of the product in a language other than French, the generic/descriptive phrase must also appear in French on the product or on a medium that is permanently attached to the product.

- For signage visible from outside premises, French must be “markedly predominant” (i.e., the space allotted to, and characters used in, the text in French must be at least twice as large) as compared to a registered trademark in another language. Before the adoption of Bill 96, trademarks could appear in another language, provided no French version of the trademark was registered, while accompanied by only a “sufficient presence of French.”

Stakeholders have requested new regulations and guidance clarifying the interpretation and scope of these amendments, which at the time of writing have yet to be published.

In the meantime, companies doing business in Québec should start assessing their trademark portfolio and existing packaging, signage, marketing, and advertising materials for compliance with Bill 96.

As illustrated by the examples above, 2022 and the first quarter of 2023 have been replete with regulatory and legal developments for the food and agribusiness industry. Many of these issues will continue to evolve over the next year, and our team will continue to monitor any developments closely.

[1] Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Nutrition Symbols, Other Labelling Provisions, Vitamin D and Hydrogenated Fats or Oils), SOR/2022-168 (20 July 2022) C Gaz II, vol 156, no 15, online: https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2022/2022-07-20/html/sor-dors168-eng.html.

[2] Ibid, Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement.

[3] Canada, Health Canada, Food labelling coordination: Joint policy statement (5 August 2021), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/legislation-guidelines/policies/food-labelling-coordination/joint-policy-statement.html.

[4] Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Implementation plan for amendments to the Food and Drug Regulations (Nutrition Symbols, Other Labelling Provisions, Vitamin D and Hydrogenated Fats or Oils) (20 July 2022), online: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-labels/labelling/implementation-plan/eng/1655824790574/1655824791481; Canada, Health Canada, Front-of-package nutrition symbol labelling guide for industry (July 2022, version 1), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/legislation-guidelines/guidance-documents/front-package-nutrition-symbol-labelling-industry.html.

[5] The new guidance has been attached as two appendices to Health Canada’s 2006 Guidelines for the Safety Assessment of Novel Foods. See Appendix 1: Health Canada Guidance on the Novelty Interpretation of Products of Plant Breeding and Appendix 2: Health Canada Guidance on the Pre-Market Assessment of Foods Derived from Retransformants (together, “new guidance”).

[6] Food and Drug Regulations, CRC, c 870, Division 28, part B [FDR].

[7] As defined in Section B.28.001 of the FDR, “genetically modify” means to change the heritable traits of a plant, animal, or microorganism by means of intentional manipulation. “Gene editing” is a newer tool of genetic modification “that can be used to generate specific modifications to the genome of living organisms by adding, removing, or altering genetic sequences at precise locations”, and refers primarily to CRISPR-Cas, as well as Oligonucleotide Directed Mutagenesis (ODM), Transcription Activator-like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and meganucleases: see Health Canada’s “Scientific opinion on the regulation of gene-edited plant products within the context of Division 28 of the Food and Drug Regulations (Novel Foods)”.

[8] Canada, Health Canada, List of Non-Novel Products of Plant Breeding for Food Use (27 March 2023), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/genetically-modified-foods-other-novel-foods/transparency-initiative/list-non-novel-products-plant-breeding-food-use.html.

[9] Canada, Health Canada, Notice of Intent to Propose Amendments to Division 28 of the Food and Drug Regulations (Novel Foods) (20 May 2022), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/public-involvement-partnerships/notice-intent-propose-amendments-division-28-food-drug-regulations-novel-foods.html.

[10] Ibid.

[11] For further discussion of the new guidance, see FDLI publication: Gene-Edited Plants Get Lighter Regulatory Touch in New Health Canada Guidance for Foods, https://www.fdli.org/2022/09/gene-edited-plants-get-lighter-regulatory-touch-in-new-health-canada-guidance-for-foods/.

[12] Regulations Amending the Fertilizers Regulations, SOR/2020-232 (11 November 2022) C Gaz II, vol 154, no 23, online: https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2020/2020-11-11/html/sor-dors232-eng.html.

[13] Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Notice to Industry – Transitional Provisions (13 November 2020), online: https://inspection.canada.ca/plant-health/fertilizers/notices-to-industry/transitional-provisions/eng/1604675250185/1604675493951.

[14] Canada, Competition Bureau, Be on the Lookout for Greenwashing (26 January 2022), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/competition-bureau/news/2022/01/be-on-the-lookout-for-greenwashing.html.

[15] Canada, Competition Bureau, Keurig Canada to Pay $3 million Penalty to Settle Competition Bureau’s Concerns over Coffee Pod Recycling Claims (6 January 2022), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/competition-bureau/news/2022/01/keurig-canada-to-pay-3-million-penalty-to-settle-competition-bureaus-concerns-over-coffee-pod-recycling-claims.html; The Commissioner of Competition v Keurig Canada Inc., CT-2022-0001, online: https://decisions.ct-tc.gc.ca/ct-tc/cdo/en/item/518827/index.do.

[16] Regulations Amending the Pest Control Products Regulations (Applications and Imports), SOR/2022-241 (17 November 2022) C Gaz II, vol 156, no 25, online: https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2022/2022-12-07/html/sor-dors241-eng.html.

[17] Pest Control Products Regulations, SOR/2006-124, s 3(1).

[18] Ibid, s 4(1).

[19] Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations and the Cannabis Regulations (Supplemented Foods), SOR/2022-169 (20 July 2022) C Gaz II, vol 156, no 15, online: https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2022/2022-07-20/html/sor-dors169-eng.html.

[20] Canada, Health Canada, List of Permitted Supplemented Food Categories (20 July 2022), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/supplemented-foods/technical-documents/list-permitted-food-categories.html.

[21] Canada, Health Canada, List of Permitted Supplemental Ingredients (03 October 2022), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/supplemented-foods/technical-documents/list-permitted-food-ingredients.html.

[22] Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations and the Cannabis Regulations (Supplemented Foods), SOR/2022-169 (20 July 2022) C Gaz II, vol 156, no 15, Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement, online: https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2022/2022-07-20/html/sor-dors169-eng.html.

[23] Cannabis Act, SC 2018, c 16, s 151.1.

[24] Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, What We Heard Report – Consultation on Canada’s proposed Guidelines for Simulated Meat and Poultry (09 July 2021), online: https://inspection.canada.ca/about-cfia/transparency/consultations-and-engagement/proposed-changes/what-we-heard-report/eng/1625073587806/1625073588369.

[25] Food and Drug Regulations, supra, ss B.01.001(1), B.14.085 to B.14.090, online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/C.R.C.,_c._870.pdf.

[26] Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Feed Regulatory Modernization (06 December 2022), online: https://inspection.canada.ca/animal-health/livestock-feeds/regulatory-modernization/eng/1612969567098/1612971995765.

[27] Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, CFIA Forward Regulatory Plan: 2022 to 2024 (09 November 2022), online: https://inspection.canada.ca/about-cfia/acts-and-regulations/forward-regulatory-plan/2022-to-2024/eng/1505738163122/1505738211563#a1_3_1.

[28] Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Guide to Timelines for Complying with the Proposed Feeds Regulations, 2022 (15 October 2021), online: https://inspection.canada.ca/animal-health/livestock-feeds/regulatory-modernization/feeds-regulations-2022/eng/1616728050480/1616728692691.

[29] Prepared with the kind assistance of Marie-Ève Gingras of the Montréal office of Torys Law Firm.

[30] An Act Respecting French, the Official and Common Language of Québec, SQ 2022 c 14, online: https://canlii.ca/t/55fcr.

[31] Charter of the French Language, CQLR c C-11, online: https://canlii.ca/t/55h16.

Update Magazine

Summer 2023

EILEEN MCMAHON is partner at Torys LLP and Chair of the firm’s Food and Drug Regulatory and Intellectual Property Practices. McMahon represents companies on regulatory clearance and intellectual property protection of products across sectors, including the food, agribusiness, life sciences (pharmaceuticals, medical devices, natural health products), and consumer products sectors.

EILEEN MCMAHON is partner at Torys LLP and Chair of the firm’s Food and Drug Regulatory and Intellectual Property Practices. McMahon represents companies on regulatory clearance and intellectual property protection of products across sectors, including the food, agribusiness, life sciences (pharmaceuticals, medical devices, natural health products), and consumer products sectors. YOLANDE DUFRESNE is counsel at Torys LLP. Dufresne’s practice focuses on the areas of intellectual property and food and drug regulatory law and advises clients in the food, agribusiness, pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device industries.

YOLANDE DUFRESNE is counsel at Torys LLP. Dufresne’s practice focuses on the areas of intellectual property and food and drug regulatory law and advises clients in the food, agribusiness, pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and medical device industries. MELANIE SHARMAN ROWAND is a senior lawyer in the Food and Drug Regulatory and IP Practice Groups at Torys LLP and a scientist with deep food regulatory expertise. Sharman Rowand’s practice focuses on food and drug regulatory and intellectual property law, with a special focus on the food and agribusiness, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology sectors.

MELANIE SHARMAN ROWAND is a senior lawyer in the Food and Drug Regulatory and IP Practice Groups at Torys LLP and a scientist with deep food regulatory expertise. Sharman Rowand’s practice focuses on food and drug regulatory and intellectual property law, with a special focus on the food and agribusiness, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology sectors. JACQUELYN SMALLEY is an associate at Torys LLP with experience advising clients in the food, agribusiness, pharmaceutical, and medical device industries on regulatory, trademark, marketing, and advertising matters.

JACQUELYN SMALLEY is an associate at Torys LLP with experience advising clients in the food, agribusiness, pharmaceutical, and medical device industries on regulatory, trademark, marketing, and advertising matters.