Deploying Agile as an Innovative Risk Management Framework in Pharma

By James F. Hlavenka & Pamela Meyer

Is it Time to Retire the Review Committee?

It’s Review Committee Day, and the project team is filled with optimistic trepidation that the day ahead won’t feel as long as it appears, with eight different projects slated for review and hundreds of comments to discuss. Figuratively gearing up for battle, team members have strategically aligned with some partners on which comments are negotiable and which are not, yet remain anxiously uncertain where the project will land once the smoke clears. More likely than not, some colleagues will leave the room frustrated and dejected, with the project being sent back for additional edits, before returning weeks later for another round of lengthy discussions with potentially the same result.

Sound familiar? If so, you may be one of the thousands of pharmaceutical industry professionals responsible for originating or reviewing industry communications and promotional material.

What Got Us Here, Won’t Get Us There

The healthcare sector is rapidly evolving, facing unprecedented volatility with new technologies, worldwide health reforms, and increasing marketplace complexity—all of which challenges traditional industry means of generating and delivering value to patients and stakeholders. Meeting patients’ needs in today’s volatile and uncertain environment is dependent upon an organization’s ability to become agile and adaptive in responding to, influencing, and leading in this rapid change. Most recently, the global pandemic has spotlighted and underscored this critical need for organizations to be able to learn, adapt, and respond to public health needs with urgency while at the same time balancing the integrity of the underlying processes intended to protect patient safety. As a result, many pharmaceutical manufacturers are now asking how they can become more agile, dynamic, and innovative while simultaneously managing risk appropriately in a highly regulated environment.

|

High Risk in a Highly Regulated Environment: A Note on Risk Management in the Pharmaceutical Industry The pharmaceutical industry is heavily regulated by federal and state laws primarily designed to protect public health and safety. As a result, the industry is accustomed to operating in a highly regulated environment with strict risk management procedures and controls. In 2018, a Public Citizen report cataloged all major financial settlements between the pharmaceutical industry and federal and state governments from 1991 through 2017, finding 412 settlements totaling a staggering $38.6 billion.[1] Risk management is therefore critical, not only to public safety but also to organizational health, and may be briefly summarized as identifying, addressing, and eliminating sources of risk before it can have deleterious effects on either the organization or public health. For industry promotion of product information to health care providers and patients, risk management traditionally occurs at various points across the creation process and spans from identification and quantification (exposing and evaluating risk opportunity and impact) to mitigation (reducing the severity of potential impact from risk), and finally, elimination or acceptance (organizational alignment on acceptable levels of risk). Failure to adequately execute and optimize risk management can significantly impact organizational health from both regulatory and commercial perspectives of risk. Organizations that impose strict controls that are too procedurally burdensome may reduce regulatory risk yet increase commercial risk by losing market opportunity, whereas those that implement controls that are too procedurally lax may increase regulatory risk yet decrease commercial risk by releasing solutions to market more quickly. |

For decades, the pharmaceutical industry has relied on strict procedures to operationalize risk management with little iteration, even where circumstances may suggest traditional approaches must be re-examined. For example, organizations may enter into successive corporate integrity agreements, yet implement the same or slightly revised versions of the same risk management procedures while expecting different results (e.g., traditional review committee approach to reviewing and approving industry communications). More often than not, these procedures fail to account for the evolving landscape in which the organization operates and, perhaps most importantly, how human mindsets and behaviors manifest and interact within the process itself, leaving organizations sub-optimally positioned to manage risk, particularly within highly volatile environments. As a result, traditional approaches to risk management have created a perception that the critical organizational capabilities of dynamism and innovation compete with, or even threaten, those of stability and regulatory compliance.

The above understanding of risk management and an organizational imperative to accelerate the delivery of innovative and differentiated solutions (and communications about those solutions) for people living with severe diseases were crucial for next steps. In 2018, a small cross-functional team of commercial, legal, and compliance colleagues at UCB, a global biopharmaceutical company, assembled to challenge the false dichotomy and viewpoint that rapid and agile innovation is incompatible with risk management and strict compliance, recognizing that “what got us here, will not get us there.” The first pilot initiative of its kind within UCB, the U.S. Neurology team upended the traditional model of pharmaceutical value creation by re-engineering its Review Committee (RC) process to an Agile framework[2] that enhances risk management while simultaneously optimizing the team’s collective capacity to design, develop, and deploy innovative solutions for patients.

Agile frameworks and ways of working are no longer a novel concept and have even become commensurate with success in our “new normal” amidst the 2020 global pandemic[3]; however, few outside the technology sector have embraced such a transformation as widely as UCB. UCB’s agile transformation was unique in that it comprehensively focused on people, process, and structure within its U.S. Neurology business, wholly re-designing the way teams collaborate, partner, and learn to transform insights into impact for patients and stakeholders alike. Rooted in UCB’s Patient Value Strategy that places patients at the center of all activities and decisions and that pulls through UCB’s organizational objective to become an agile organization, the UCB U.S. Neurology agile transformation yielded significant learnings for the larger organization. Notably, the agile transformation delivered substantial benefits to its patients, people, culture, and internal operations by way of improved time to market, enhanced employee satisfaction, and reduced errors and costs. In the early days of the pandemic, the team’s Agile framework and capabilities enabled an effective and rapid transition to work-from-home during the global pandemic without delay, confusion, or misalignment, greatly contributing to the seamless deployment of risk management in an uncharted climate.[4] The team’s ability to successfully operationalize this agile transformation is not only catching the eye of UCB globally, as other departments begin operationalizing Agile ways of working, but from industry peers that have begun to pilot their own agile approaches, with many asking “how did you do it?”

From Adversarial Problem-Identification to Collaborative Solution-Generation

A decades-old process in the pharmaceutical industry, the review committee[5] is primarily designed and intended to mitigate risk by requiring regimented, linear coordination between project originators as well as medical, legal, compliance, and regulatory partners to review, edit, and approve industry communications and in-market solutions for health care practitioners and patients. The RC process is an example of the popular metaphor of project management as a relay race. One portion of the team leads off the relay by creating its part of the project in a silo (e.g., the marketing concept and content) and then hands it off to the next leg of the race (e.g., the regulatory reviewer), who often finds issues with the first team’s work and, in a departure from the relay metaphor, hands it back for revisions. With few exceptions, by the time the project makes its way to the oft-dreaded “review day,” the relay team is demoralized in anticipation of further problem-finding and the knowledge that they inevitably will be asked to return once again to the starting blocks.

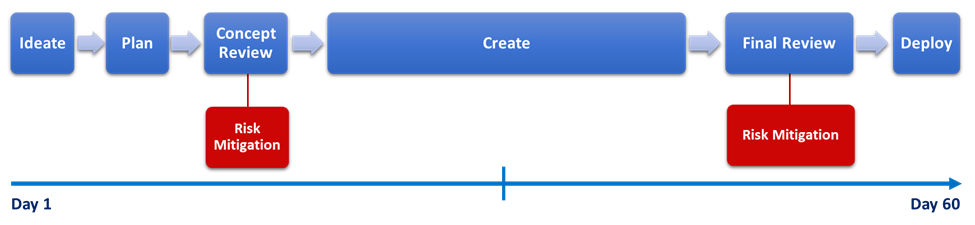

From a risk management perspective, this linear approach to creating solutions bookends the majority of risk mitigation at the outset and conclusion of the process. Risk identification and mitigation are viewed as “moments in time” rather than fluidly incorporated throughout the process (see Figure 1). The intention of this approach is to identify and avoid risk at the front end of the process prior to engaging in the development of content (i.e., “concept review”) and to mitigate or eliminate risk at the tail end of the process, in a detailed hands-on review of created content (i.e., “final content review”). While touchpoints between content originators and cross-functional reviewers are encouraged throughout the process, often there are no process-required interactions between concept review and final content review. As a result of this lack of continuous cross-functional interaction, as concepts materialize into claims and content, an unintended consequence of this approach is that levels of risk increase over time in an unmitigated manner throughout the process, awaiting identification, mitigation, and resolution at the conclusion of the creation cycle, which often results in project delay, resource waste, and employee disengagement.

A simple analogy to this phenomenon is reflected in the “telephone game” many of us played as children. What started off as, “Clifford is a big red dog that loves to play,” from child 1 to child 2 ended as, “it is going to rain cats and dogs” between child 9 and child 10. What is generally agreed to between the review team at concept review evolves as the piece is independently developed by the agency and marketing team over subsequent weeks and months, which unintentionally loses the important nuance and minutiae of the expert advice of the reviewers between concept review and final review.

Figure 1

While well-intended, the traditional RC process is strictly oriented toward coordinated problem-identification between cross-functional experts—rather than collaborative problem-solving by a cross-functional team—which can result in an adversarial culture that inhibits rather than enhances learning, communication, and collaborative partnership. These unintentional outcomes of a process designed primarily for risk management can have significant consequences for organizational risk, where peers withhold information from one another or avoid one another entirely outside mandated coordination. Shifting to an approach that prioritizes cross-functional collaboration, diversity of thought, and continuous learning throughout the creation process is a critical strategy for risk management, enabling teams to mitigate risk while simultaneously enhancing trust, engagement, and technical expertise.

The Agile Alternative

When the UCB U.S. Neurology team set out to design and deploy an approach to creating solutions that would enable them to meaningfully respond to localized patient needs in an environment of rapid change and high-stakes compliance, they turned to the technology sector for inspiration. Around 2000, traditional technology firms reached a tipping point where they were innovating so slowly that their new products were obsolete at launch. Consumer demands, as well as innovation and technology, were rapidly changing, and those who failed to learn, adapt, and evolve were quickly left behind. The old way of releasing software using the more linear, relay race approach (sometimes referred to as “waterfall”) simply could not keep up with such rapid changes. Fast-moving innovators that shifted to a cross-disciplinary, iterative approach were able to outperform by adapting more quickly to new technical advances, customer needs, and expectations, ultimately disrupting entire industries such as home cinema (Netflix), brick and mortar storefronts (Amazon), and transportation (Uber).[6] The organizations that flourished had a significant trait in common: they prioritized customer value and operated within Agile frameworks, deploying short, iterative cycles of value creation that prioritized “people and interactions over strict processes and tools.”[7]

At its core, Agile is a set of principles and practices that help leaders, teams, and entire organizations anticipate and respond to change quickly. To become Agile, organizations must reimagine how they collaborate and communicate across interfaces, valuing a transversal network compared to siloed departments of expertise. Agile organizations rely less on silos and decision-making hierarchies and more on networks of empowered cross-functional teams focused on prioritized and iterative learning cycles for value creation. Agile’s well-documented results were intriguing; however, the tech sector is not pharma, and UCB’s legal and compliance team members were understandably cautious.[8] After all, the majority of legal and regulatory standards are primarily intended to protect the public interest and patient health—not enhance speed of innovation. UCB, like all pharma companies, relies heavily on standard operating procedures (SOPs) to establish non-negotiable compliance principles and operating procedures. Standardized SOPs primarily act as critical controls to enable compliance and auditing and are rarely designed to enhance collaborative innovation and creativity. During their initial pilot, the UCB team set out to answer a critical question: could Agile enable the retention of critical non-negotiable compliance controls and simultaneously unlock enhanced adaptability, learning, and efficiency? Additionally, could the team become quicker at making decisions while ensuring that those decisions remain great ones for the organization and its patients?

|

Striking a Critical Balance The most common misperception about Agile is that its sole focus is to become faster and more dynamic. To sustain the ability to create value and thrive as adaptable systems, agile organizations require a critical balance of both stable and dynamic capabilities. Rather than compete with each other, these capabilities symbiotically complement and enable each other. Dynamic practices enable nimble and quick response to new challenges and opportunities, such as novel patient needs and evolving market conditions, whereas stable practices enable reliability and efficiency, such as sustaining organizational core values and governance. Together, dynamism and stability enable companies to mobilize quickly and remain nimble by empowering teams to act and deliver high quality solutions, equipping such organizations to thrive in volatile and rapidly changing environments. |

Agile Frameworks as Risk Mitigation

Aligned to UCB’s Patient Value Strategy,[9] the UCB U.S. Neurology team deployed an Agile framework that focuses on delivering meaningful and prioritized solutions quickly through short, iterative co-creation cycles. Each cycle is composed of a regular and predictable cadence of team interactions to enable streamlined, transparent, and priority-driven information sharing, communication, and decision-making. At the core of the Agile approach are integrated and self-directed teams inclusive of traditional content originators (e.g., marketing, medical) and functional reviewers (e.g., legal, compliance, regulatory) who are empowered and jointly accountable for end-to-end decision-making and value creation. Notably, cross-functional partners are integral members of these teams, flowing through the work as needs require throughout the solution creation cycle rather than providing input solely at select moments as required within the traditional RC process. By nature of the short, iterative creation cycles, the framework has an intentional bias toward learning and rapid delivery while simultaneously enabling regular risk identification and mitigation and impediment removal early and often.

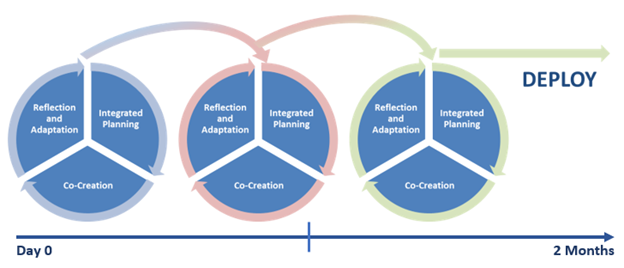

Contrary to the traditional approach, wherein the process is to create solutions and conclude with a visit to the review committee, Agile value creation actively and fluidly integrates risk management throughout the creation cycle via integrated cross-functional teams, thereby mitigating and reducing levels of risk as the creation process unfolds over time. This approach addresses organizational risk as solutions are being built while simultaneously optimizing and enhancing efficiencies by eliminating delay at the conclusion of development. Documentation and cross-functional feedback and direction become critical enabling components embedded within the team-based approach rather than simply a procedural “step” to get through. In practice, this means cross-functional teams walk in lockstep from the initial strategic planning of solutions, to co-creation of the solution itself, to finally taking space to reflect on what they created and how they created it as a team before repeating the cycle until the solution is ready for deployment. (See Figure 2). Team members are able to identify, evaluate, mitigate, and eliminate risk throughout each creation cycle. These working cycles are quick—generally, only a couple of weeks at a time—to enable rapid iteration and learning as solutions are being built.

An agile team builds a 10-page patient brochure by breaking the project down into three, two-week creation cycles: 1) the team conceptually designs the framing and flow of the brochure with skeleton outline and proposed visual and verbal claims; 2) the team creates content for first five pages of the brochure; 3) the team creates content for last five pages of the brochure. On week four during the second cycle, the team learns of patient insights that require them to shift claims and content. In discussions with cross-functional team partners, they align on how best to compliantly execute the insights, enabling them to evaluate the impact on the piece in real-time and pivot as required, while continuing to build with the new information learned in the third cycle.

Compare the approach above with an originator conceptualizing the 10-page brochure in a hypothetical review committee setting, taking into account risk-based guidance from cross-functional reviewers, and then dispersing for six weeks to develop the content, only to arrive back at review committee and learn the pivot made to claims during week four negatively impacted all other content, which will require the team to go back and to redesign the entire piece, before finally coming back to review committee to assess again.

Figure 2: Cross-Functional Creation Cycles

“We shifted to finding solutions as a group and trusting each other that we aren’t in there to just say ‘no’ and don’t want to just not do this, but we’re all in there together with the common focus and goal. And we are all there to find a solution.”

—Kristy Pucylowski, Medical Lead, U.S. Neurology at UCB

It may be tempting to read the shift from a linear to cyclical approach as merely operational. However, this reading would miss its most significant value to the patient and the organization: iterative, Agile frameworks engage and harness the power of a cross-functional team’s diversity of experience and expertise[10] as well as their power to engage the uniquely human ability to innovate and co-create as they inspect, learn, and adapt. These capacities transcend the operational shifts embedded in Agile and cannot be fully captured in the black and white text of any SOP or procedural manual. With this critical social dynamic in mind, cross-functional teams leverage their diverse expertise to create value and manage risk by collaboratively practicing four essential elements described below:

1) Developing an Agile Mindset

Companies that embrace agile ways of working typically refer to their process as an agile transformation rather than an agile implementation. This is not a small distinction. Shifting to agile ways of working is first and foremost a shift in mindset. The hallmarks of an agile mindset are an orientation toward learning and adaptation over planning and control, leading to a culture of trust and bias for action. An agile mindset acts as a critical enabling foundation to agile ways of working, guiding individuals to embrace vulnerability, imperfection, and growth in the face of adversity and uncertainty. Thinking in an agile manner prioritizes curiosity in place of critique, pushing individuals to abandon mental autopilot to always learn the “why” before jumping to “how.” This natural orientation toward learning organically reduces fear in ambiguity and discomfort, transforming fright into fuel for creativity and innovation in new and unfamiliar circumstances. From a risk management perspective, agile mindsets enable teams to safely ask questions of one another and quickly surface and learn from mistakes and errors, rather than avoiding tough issues that might be put off in the more linear, traditional approach to creating solutions.

Shifting to an agile mindset is neither instant nor effortless. Leaders and members of the cross-functional agile teams at UCB engaged in a number of activities to develop and sustain this mindset shift, including participating in a series of highly interactive leadership development sessions over the course of the transformation. Each of these sessions was designed to help team members become more comfortable with being uncomfortable: to feel more confident communicating, collaborating, and coordinating resources across traditional silos, all while learning and adapting through iterative cycles of co-creation. UCB is not alone in prioritizing a mindset shift as part of its overall agile transformation; the ability to adopt an agile mindset is so critical to overall agile success that a recent joint study by Forbes Insights and the Scrum Alliance of 1,000 C-suite executives across industries found that 83% of respondents cite an agile mindset/flexibility as the most essential characteristic of today’s C-suite.[11]

2) Integrated Planning and Prioritization

On the outset of the agile value creation cycle is an integrated planning session where strategic goals and prioritization of effort for the upcoming work cycle are transparently displayed and discussed with all stakeholders involved in the upcoming work. During this time, cross-functional teams plan out their work aligned to the prioritized goals, setting joint accountability by assessing relative effort required and available capacity across the working period. For instance, two teams may identify the need to advance portions of a market access flashcard, an update to a product website, and a healthcare provider communication. Cross-functional partners may then weigh in with the relative effort required for each project, confirming that they have the required capacity for the upcoming cycle. With this information, the teams will prioritize the projects in order of patient impact, thereby aligning with all stakeholders on where the work should flow first and preemptively ensuring the highest priority project is progressed if an unaccounted-for conflict were to arise after planning. The teams may then leave this session with full transparency of the upcoming work and joint accountability for their commitments during the working period.

At this phase, risk is assessed at both the strategic level (across all projects) as well as at the tactical project level, providing those responsible for risk management a dual lens rarely captured within the review committee process alone. Qualitative, cross-functional feedback has confirmed the value of this operational engagement, noting that effort spent on risk mitigation at the tactical level alone may be minimized, wasted, or even largely negated if it is not considered within the larger strategic context. Moreover, with transparent prioritization of projects and alignment of capacity upfront, team members will ensure collaborative space, consistent for all involved stakeholders to more effectively enable thorough and comprehensive thought partnership. The rigorous levels of transparency and collaborative prioritization are another risk-management practice built into Agile. Without this level of discipline, teams may quickly discover that “where everything is a priority, nothing is a priority,” and reviewers may become overwhelmed with work, creating an exponential risk for errors in execution.

Another critical aspect of these interdisciplinary teams is that their embedded transparency and cycles of inspection and adaptation build trust and psychological safety,[12] both of which are essential to a culture of free-flowing communication, collaboration, and shared accountability. Management literature is filled with retrospectives of catastrophic failures caused, at least in part, by cultures that prioritized expediency over quality and value.[13] The issue of trust and psychological safety has also been directly linked to patient safety in healthcare settings. When individual caregivers feel that their observations and experience are valued and wanted, they are more likely to speak up to those in higher status roles, namely physicians.[14]

3) Iterative, Empirical Co-Creation Cycles

At the heart of agile ways of working are short co-creation cycles (i.e., sprints or working periods), that enable rapid testing, learning, and iteration. Short working cycles enable teams to better understand the work, relative effort, and capacity required of a project, leading to aligned and informed teams (e.g., estimating work in a nuanced manner over a two-week period is much easier compared with estimating work over a two-month period). Creativity and experimentation are also encouraged in shorter working cycles, as the risk of failure is mitigated by the timeframe of the working period. Regular touchpoints within the working cycle (daily to weekly in frequency) also enable teams to rapidly address any new discoveries or risks that arise post-planning.

Rather than attempting to predict the outcomes of long-range planning and all associated opportunities for risk to arise, as the traditional RC process necessitates at the concept review phase, Agile relies on empirical evidence of value and compliance to drive each co-creative cycle as solutions are being built. Addressing risk early and often throughout each cycle also optimizes team resources, ensuring they do not waste time, money, and effort on non-viable pathways that may evolve beyond initial concept design. In this way, the team metaphor shifts from one of a relay race to a rugby scrum (from which the Agile framework, known as “Scrum,” derives its name), whose players make their way down the field by nimbly passing the ball back and forth and quickly adapting as they encounter new developments.

4) Feedback, Learning, and Adaptation

At the close of each Agile creation cycle is intentional and protected time for the team to pause, reflect, and provide feedback about the work completed (the “what”) via a sprint review, and how the colleagues performed as a team (the “how”), conducted separately and referred to as a retrospective in Agile frameworks. Through actionable feedback and sheer proximity to cross-functional expertise, the team collectively upskills one another, creating interdisciplinary fluency that mitigates future opportunities for risk and errors otherwise rooted in naivety and lack of understanding. By protecting space at the conclusion of each working cycle to discuss the “what” and the “how,” the UCB team institutionalizes a culture of feedback, reflection, and continuous learning for maximum team performance, growth, and improvement. This enhanced cross-functional understanding, often missing in the traditional RC process, also helps to reduce errors and accelerate resource efficiencies.

Value Creation Through Risk Management

The goal of this article is to dispel the common misconceptions that business agility and Agile ways of working are fraught with potential compliance and regulatory pitfalls by showing how risk management is built into the framework itself and critical to its successful operation. Indeed, as the UCB team observed, Agile ways of working complement rather than contradict the team’s ability to manage risk. The quantifiable impact of integrating risk management into the value creation process is both measurable and striking for patients and organizations alike: within the first nine months of the transformation, the UCB team reduced errors and realized resource efficiencies, cutting average development cycles by 26% and increasing market-readiness by 25% compared to historical review committee data. For UCB, this translates to an organizational capacity to become more responsive to the needs of the patients they serve. Moreover, team members remarked on how this new way of working positively impacted their team culture and productivity, with a regulatory partner stating that the Agile framework enabled the smoothest indication launch he had ever been a part of, and an agency partner noting that solutions deployed within the Agile framework were of the highest quality she had seen since working with UCB.

Remaining true to an agile mindset of continuous learning, and about 18 months after shifting to the Agile framework, the UCB team quantitatively measured the impact on its culture by surveying team sentiment and feedback at the end of every creation cycle (every three weeks) for six months. They found sustained increases in favorability scores across vectors contemplating ways of working and culture compared with historical data. Namely, the team self-reported a 90% favorability rating for collaboration and 88% favorability rating for satisfaction, in addition to significant sustained increases in favorability ratings for clarity in communication (76%) and decision-making (75%). Cross-functional partners noted in survey comments that they now learn from each other while they work, rather than updating one another on what was completed in isolation. In doing so, they note that they intentionally take time to teach each other about their respective functional areas to enhance team knowledge and their collective ability to work together. As a result, they have reported that they are now better equipped to ask each other questions and learn how to better leverage each other’s talents to create better solutions for the patients they serve.

UCB’s results demonstrate that transversal communication, collaboration, and learning in an adaptive Agile model unlocks the true potential of internal engagement and ignites an ability to be truly responsive to patients’ changing needs while simultaneously confirming an analysis of over a decade of research that directly links employee satisfaction to significant increases in productivity and accuracy on tasks.[15] These results also elucidate that frequent and collaborative team engagement through an Agile framework simultaneously achieves what traditional SOPs both can and cannot; by traveling together toward the goal line of patient and stakeholder value, agile teams collectively advance value creation and risk management in real time, while also incrementally building trust and enabling a diverse and inclusive culture of cross-functional partnership to flourish. This very capacity of the framework was demonstrated as UCB observed the positive impact of its agile transformation on its people culture. In response to the killing of George Floyd in 2020,[16] the culture of transparency, learning, and collaboration served as a foundation for team members across the organization to engage in courageous conversations and to quickly launch new initiatives to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion. UCB’s ability to respond rapidly and with transparency is fostering a more robust, value-aligned culture, with improved communication and organizational trust that, while not the primary motivation, helps the organization to reduce risk and encourage ethical decision-making in its people practices and daily engagement.

A Way Forward

As Agile ways of working move from an intrigue to an organizational imperative in today’s highly volatile environment, we hope the learnings from this snapshot of UCB’s agile transformation provide comfort and inspiration for industry professionals that Agile is not only compatible with—but can further enhance—risk management in highly regulated environments while simultaneously better equipping such organizations to benefit the patients they serve. As demonstrated by UCB, patients stand to realize significant benefits from organizations that are willing to make the shift to Agile; however, the shift is neither instant nor without friction. Agile ways of working challenge traditional bureaucratic organizational design at its core, including how we structure, how we govern, and how we partner. Perhaps most importantly for our industry, it challenges conventional risk management ideology and norms, shifting our understanding of cross-functional experts solely as ad-hoc gatekeepers to critical and integrated partners in strategic co-creation. This approach recognizes that a culture of learning that prioritizes diversity of thought and experience enhances both innovative value creation and risk management, ultimately enhancing and elevating organizational capacity to positively impact the populations they serve. Organizations that have encountered obstacles to rapidly responding to patient needs, along with cumbersome and sometimes counterproductive aspects of traditional risk management processes described herein, may discover that it is time to embrace this new holistic way of working and seriously consider retiring their traditional review committee.

It is early spring 2020, and the pandemic is surging across the country. The UCB U.S. Neurology team learns how the massive shift to telemedicine nearly overnight creates a paradigm shift in the way epilepsy patients receive care. Based on emerging physician and patient insights regarding the anxieties and challenges associated with remote care, the UCB team quickly pivots to prioritize the development of a remote care patient guide that provides tips and suggestions to patients for more effective remote care engagements with their providers. When the stakes for patient care are at their highest, the team taps the capacities they built through their agile transformation to seamlessly mitigate risk and accelerate patient value and impact.

References

Carolyn Dewar, Sherina Ebrahim & Michael Lurie, Agility: Mindset Makeovers are

Critical (Apr. 30, 2018), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-organization-blog/agility-mindset-makeovers-are-critical.

Mary Poppendieck & Tom Poppendieck, Implementing Lean Software Development: From Concept to Cash (Addison-Wesley 2006).

UCB’s U.S. Neurology Team Wins EyeForPharma Award for Agile Transformation UCB, UCB, Inc. (Dec. 12, 2019), https://www.ucb-usa.com/stories-media/UCB-U-S-News/detail/article/UCB%E2%80%99s-U-S-Neurology-Team-Wins-EyeForPharma-Award-for-Agile-Transformation.

[1] Michael A. Carome, New Report on Big Pharma Settlements Highlights Need for Tougher Enforcement (Mar. 14, 2018), https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2018/03/new-report-on-big-pharma-settlements-highlights-need-for-tougher-enforcement/.

[2] When referring to a specific Agile framework, such as Scrum, the authors capitalize the word Agile. When used to refer to the broader capability of agility, the word is not capitalized.

[3] McKinsey & Company, An Operating Model for the Next Normal: Lessons from Agile Organizations in the Crisis (June 25, 2020), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/an-operating-model-for-the-next-normal-lessons-from-agile-organizations-in-the-crisis.

[4] Brad Chapman, Finding Stability in the Storm (July 16, 2020), https://www.ucb-usa.com/stories-media/UCB-U-S-News/detail/article/Finding-Stability-in-the-Storm.

[5] This traditional process may also be referred to as promotional review committee (PRC), compliance clearance committee (CCC), or copy approval team (CAT), among other names.

[6] Tom Goodwin, The Battle for Customer Interface, TechCrunch (Mar. 3, 2015), https://techcrunch.com/2015/03/03/in-the-age-of-disintermediation-the-battle-is-all-for-the-customer-interface/; Steve Denning, How Amazon became Agile, Forbes (June 2, 2019), https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2019/06/02/how-amazon-became-agile/#3aa8103c31aa.

[7] Martin Fowler & Jim Highsmith, The Agile Manifesto, 9 Software Development 29–30 (2001).

[8] Darrell Rigby, Jeff Sutherland & Hirotaka Takeuchi, Embracing Agile, Harvard Bus. Rev., May 2016, at 40–48, 50.

[9] About UCB in the United States, UCB, Inc. (2020), https://ucb-usa.com/UCB-in-the-U-S/UCB-in-the-U-S.

[10] David Rock & Heidi Grant, Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter, Harvard Bus. Rev. (Nov. 4, 2016), https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter.

[11] Scrum Alliance & Forbes Insights, The Elusive Agile Enterprise: How the Right Leadership Mindset, Workforce and Culture Can Transform Your Organization (2018), https://www.scrumalliance.org/ScrumRedesignDEVSite/media/Forbes-Media/ScrumAlliance_REPORT_FINAL-WEB.pdf?_ga=2.2544179.2096796420.1663005489-1701085360.1663005489.

[12] Amy C. Edmondson, Managing the Risk of Learning: Psychological Safety in Work Teams, in International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork 255–75 (Michael A. West, Dean Tjosvold & Ken G. Smith Eds., Wiley 2002).

[13] William Langewiesche, What Really Brought Down the Boeing 737 Max?, N.Y. Times (Sept. 21, 2019); Bill Nelson, Total Recall: Internal Documents Detail Takata’s Broken Safety Culture and the Need for a More Effective Recall Process, Off. of Oversight & Investigations, U.S. Senate (Feb. 2016), https://www.commerce.senate.gov/services/files/04c489c1-36e8-4037-b60b-c50285f3e436; Brian Berger, Columbia Report Faults NASA Culture, Government Oversight, Space.com (2013), https://www.space.com/19476-space-shuttle-columbia-disaster-oversight.html.

[14] Lucien L. Leape, Troyen A. Brennan, Nan Laird, Ann G. Lawthers, Russell Localio, Benjamin A. Barnes, Liesi Hebert, Joseph P. Newhouse, Paul C. Weiler & Howard Hiatt, The Nature of Adverse Events in Hospitalized Patients—Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II, 324 New Eng. J. Med. 324, 377–84 (Feb. 7, 1991); Hannes Leroy, Bart Dierynck, Frederik Anseel, Tony Simons, Jonathon R. B. Halbesleben, Deirdre McCaughey, Grant T. Savage & Luc Sels, Behavioral Integrity for Safety, Priority of Safety, Psychological Safety, and Patient Safety: A Team Level Study, 97 J. Applied Psych. 1273 (2012).

[15] Shawn Achor, The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology that Fuel Success and Performance at Work (2010).

[16] Evan Hill, Ainara Tiefenthäler, Christiaan Triebert, Drew Jordan, Haley Willis & Robin Stein, How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody, N.Y. Times (2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/george-floyd-investigation.html.

Update Magazine

Fall 2022

JAMES F. HLAVENKA is the Head of Strategy & Operations for U.S. Neurology at UCB and helped design, lead, and operationalize the agile transformation within UCB U.S. Neurology. Prior to his commercial roles at UCB, Hlavenka served as Senior Counsel to the UCB U.S. Neurology and Immunology Sales, Marketing, and Medical Affairs teams where he provided strategic advice, education, training, and legal direction on FDA labeling and promotional matters, healthcare fraud and abuse laws, product liability, privacy, and other laws impacting the commercialization of UCB products.

JAMES F. HLAVENKA is the Head of Strategy & Operations for U.S. Neurology at UCB and helped design, lead, and operationalize the agile transformation within UCB U.S. Neurology. Prior to his commercial roles at UCB, Hlavenka served as Senior Counsel to the UCB U.S. Neurology and Immunology Sales, Marketing, and Medical Affairs teams where he provided strategic advice, education, training, and legal direction on FDA labeling and promotional matters, healthcare fraud and abuse laws, product liability, privacy, and other laws impacting the commercialization of UCB products. PAMELA MEYER is the author of The Agility Shift: Creating Agile Leaders, Teams and Organizations and three other books on innovation, learning and change. As President of Meyer Agile Innovation, she works with businesses across sectors that need to be more agile and innovative. In addition to her work with organizations, Meyer teaches courses in business creativity, organizational change and adult learning at DePaul University in Chicago, where she served as director of the Center to Advance Education for Adults and Faculty Fellow at the Center for Creativity and Innovation, part of the Driehaus College of Business and the Kellstadt Graduate School of Business.

PAMELA MEYER is the author of The Agility Shift: Creating Agile Leaders, Teams and Organizations and three other books on innovation, learning and change. As President of Meyer Agile Innovation, she works with businesses across sectors that need to be more agile and innovative. In addition to her work with organizations, Meyer teaches courses in business creativity, organizational change and adult learning at DePaul University in Chicago, where she served as director of the Center to Advance Education for Adults and Faculty Fellow at the Center for Creativity and Innovation, part of the Driehaus College of Business and the Kellstadt Graduate School of Business.