340B and the Warped Rhetoric of Healthcare Compassion

By Peter J. Pitts & Robert Popovian

Introduction: A 340B Primer

The 340B Drug Pricing Program is a federal program that entitles eligible hospitals to manufacture discounts on purchases of drugs administered or prescribed in an outpatient setting. The discounted drugs can be provided to patients regardless of their ability to pay or their insurance coverage status. The 1992 statute under which the program was established states that program savings are intended to “stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.”[1]

The 340B program was an honest attempt to enhance prescription drug access for vulnerable, low-income, and uninsured patients.

As a condition of participating in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), drug manufacturers are required to participate in 340B, which provides discounts on outpatient drugs purchased by eligible healthcare organizations, many of which are safety net providers treating high percentages of uninsured or low-income patients. In 2020, total sales of 340B-discounted drugs were estimated to be $38 billion, or roughly 7% of the total U.S. drug market.[2]

The program requires biopharmaceutical firms to offer considerable discounts on their drugs to certain hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients. The 340B program allows eligible healthcare clinics and hospitals (“covered entities”) to purchase outpatient drugs.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, oversees the 340B program through its Office of Pharmacy Affairs (OPA).[3]

The Road to Broader Access to Medicines is Paved with Good Intentions

For too many years, too few policymakers paid any attention to the 340B drug discount program, blindly accepting the myth that non-profit hospitals and other covered entities were selflessly using 340B savings to “stretch scarce federal healthcare resources” in service of our most vulnerable patients.

Follow the Money—And There’s a Lot of It

The 340B Drug Pricing Program is now unambiguously the second-largest government pharmaceutical program, based on net drug spending. But unlike such programs as Medicare Part D and Medicaid, 340B lacks a regulatory infrastructure, well-developed administrative controls, and clear legislation to guide the program.

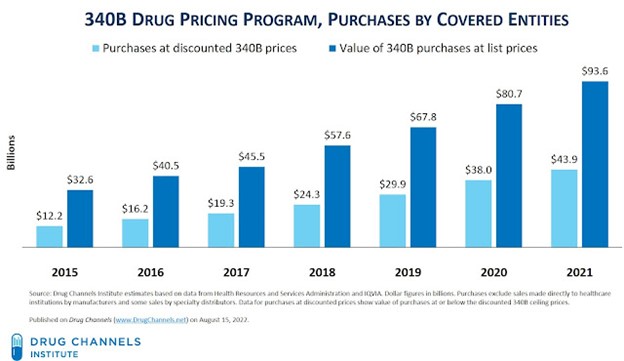

For 2021, discounted purchases under the 340B program reached a record $43.9 billion—an astonishing $5.9 billion (+15.6%) higher than its 2020 counterpart. Hospitals accounted for 87% of these skyrocketing 340B purchases.[4]

Astounding Growth

The chart below documents the 340B program’s exponential growth.

Advocates Doth Protest Too Much

340B advocates have been screaming that “drug companies are cutting 340B,” but the data tell a very different story. Per the new Drug Channels report:

- The compound average growth rate (CAGR) of 340B purchases was 23.8% from 2015 through 2021. Over the same period, manufacturers’ net brand-name drug sales (excluding COVID-19 vaccines) grew at an average annual rate of less than 4%.

- In 2021, the list-to-340B gap—the difference between purchases at list prices and purchases at 340B discounted prices—grew to $49.7 billion (=$93.6 minus $43.9). That’s $7.0 billion higher than the 2020 gap.

- The estimated total value of pharmaceutical manufacturers’ gross-to-net reductions for brand-name drugs was $236 billion in 2021. (See Warped Incentives Update: The Gross-to-Net Bubble Exceeded $200 Billion in 2021.) Therefore, manufacturers’ discounts under the 340B Drug Pricing Program accounted for more than one-third of the total gross-to-net reductions for brand-name drugs.

Deciphering Misleading and Dangerous 340B “Spin”

A recent headline in RevCycle Intelligence reads, “Operating margins for 340B [Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH)] hospitals fell from 3.5 percent in 2019 to -6.1 percent in 2020, but the facilities still delivered $41.6 billion in uncompensated care.”[5] This is truthful but misleading. According to a report cited in the article,[6] “Hospitals experienced revenue losses when the COVID-19 pandemic hit as patients delayed non-urgent care and hospitalizations increased. 340B DSH hospitals saw a 74 percent decrease in operating margins between FY 2019 and FY 2020, going from -3.5 percent to -6.1 percent. During the same period, operating margins for non-340B hospitals increased from 2.9 percent to 3.5 percent. Researchers attributed operating margin changes to uncompensated care delivery, public payer shortfalls, and the provision of typically unprofitable services.”

The report concludes, “340B recognizes the special challenges that 340B DSH hospitals face in providing care to patients with low incomes and other patient populations in need. This report provides additional evidence that 340B hospitals continue to fulfill the program’s purpose as set out by Congress in 1992.”

Unfortunately, the report has carefully cherry-picked the hospitals it considers worthy of inclusion. The clever omission of hospitals not classified as Disproportionate Share Hospitals make the report and its conclusions about the 340B program both inaccurate, untruthful, and misleading. But a more careful consideration based on a “follow the money” premise tells a more comprehensive and concerning story.

Warping 340B—at Warp Speed

Some hospitals and hospital systems have come to treat 340B less as an assistance program and more as a profit center. Their behavior is made possible by the fact that under current law, providers are under no obligation to reserve the discounts for needy patients or even report what they do with the savings. Just the opposite is happening. Eligible hospitals will obtain all their 340B medications from a drugmaker at the discounted 340B price and then bill privately insured patients—and even uninsured patients—for the drug’s full list price, helping themselves to the difference as pure profit. While the law requires these patients to meet certain criteria, hospitals have found ways to maximize profits under the program.

Consequently, most prescriptions filled at contract pharmacies are dispensed to patients who have prescription drug insurance—not to uninsured or financially needy patients.[7] That’s why Medicare and other third-party payers end up being responsible for the balance of the profit earned by a 340B covered entity and the contract pharmacy. In the real world, this is called stealing.

Not surprisingly, congressional and regulatory neglect has resulted in significant financial abuse. Today there is ever-increasing evidence of the program’s out-of-control scope and a growing chorus from all corners of government who are finally beginning to see the 340B drug discount program for what it has become—a moneymaker for hospitals wrapped in the rhetoric of healthcare compassion.

Tar Heel Hospitals Get Tarred

340B abuse is not a new issue. In September 2012, Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA) wrote to three North Carolina hospitals regarding their participation in the 340B program. Specifically, he requested the three hospitals share how much revenue they earn by participating in the 340B program, the breakdown of the 340B payer mix, and how they reinvest those 340B dollars back into serving the most vulnerable patients.

All three North Carolina hospitals provided a summary of revenue generated by

participating in the 340B program from 2008. Below is a revenue summary of Duke University

Health System, University of North Carolina Hospital, and Carolinas Medical Center (now known as Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center)[8]:

|

Carolinas Medical Center |

UNC |

Duke |

|

2008: $12,970,012 |

2009: $33,087,329 |

2009: $88,953,570 |

|

2009: $16,697,500 |

2010: $38,451,076 |

2010: $109,700,404 |

|

2010: $16,910,956 |

2011: $52,580,763 |

2011: $131.759.091 |

|

2011: $21,065,620 |

2012: $65,391,050 |

2012: $135,539,459 |

All three North Carolina hospitals provided a breakdown of their 340B patients. Below is a chart that illustrates 340B patients with respect to the three North Carolina hospitals:

|

Hospital |

Medicare |

Medicaid |

Self-pay |

Commercial |

|

Carolinas Medical Center |

2009: 24.2% 2010: 24.4% 2011: 25.6% 2012: no data |

2009: 18.5% 2010: 18.2% 2011: 18.3% 2012: no data |

2009: 11.5% 2010: 11.3% 2011: 11.3% 2012: no data |

2009: 42.2% 2010: 42.6% 2011: 41.9% 2012: no data |

|

UNC |

2009: 27.5% 2010: 16.8% 2011: 23.1% 2012: 32.9 |

2009: 10.3% 2010: 7.2% 2011: 9.7% 2012: 12.5% |

2009: 20.0% 2010: 10.3% 2011: 12.0% 2012: 13.7% |

2009: 27.9% 2010: 28.0% 2011: 22.6% 2012: 29.6% |

|

Duke |

2009: 14% 2010: 17% 2011: 19% 2012: 19% |

2009: 7% 2010: 10% 2011: 8% 2012: 9% |

2009: 5% 2010: 5% 2011: 4% 2012: 5% |

2009: 74% 2010: 69% 2011: 68% 2012: 67% |

In March 2013, Senator Grassley pointed out to then-HRSA Administrator Dr. Mary K. Wakefield, that these numbers paint a very stark picture of how hospitals are reaping sizeable 340B discounts on drugs and then turning around and upselling them to fully insured patients covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or private health insurance in order to maximize their spread.

For example, only 5% of the patients who received discounted drugs under Duke University Hospital’s 340B program were uninsured. Most of the remaining patients who received discounted drugs paid Duke University Hospital full price through private insurance.[9]

As the Government Accountability Office (GAO) points out in its September 2011 report, “most [covered entities] reported that they generated more 340B revenue from patients with private insurance and Medicare compared to other payers.”

An October 2021 analysis by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the North Carolina State Health Plan[10] shows that 340B is not the only way North Carolina hospitals reap profits from government programs intended to benefit the poor. It revealed that while North Carolina hospitals are more than three times more profitable than the national average, their charity care spending has not kept pace.

The report—commissioned by NC Treasurer Dale R. Folwell, CPA, who invited researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health to extend their national study of hospitals’ charity care spending to North Carolina—found that the state’s largest nonprofit hospital systems reaped tax breaks worth more than an estimated $1.8 billion in 2019–2020. Yet for the majority of these systems, charity care spending did not exceed 60% of the value of their tax breaks.

According to the analysis, only four of the state’s 15 most profitable hospitals delivered enough charity care to exceed the value of their tax exemptions. Atrium Health and Duke Health, whose hospitals were cited as profiting from the 340B program in Senator Grassley’s report, show some of the highest gains from tax breaks versus charity care spending. Atrium received $440.1 million in tax exemptions and spent $260.1 million on charity care, while Duke Health received $225.8 million in tax exemptions and provided $133 million in charity care.

“Charity care is the heart of what it means to be a nonprofit hospital,” Treasurer Folwell said. “Our hospital systems justify overcharging state employees and taxpayers by pointing to their charity care costs. But now we know that is not fully accurate. They are profiting on the backs of sick patients.”

Where Do 340B Savings Go? Hospitals and the “Fair Share Deficit”

Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) serve a significantly disproportionate number of low-income patients and receive payments from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services to cover the costs of providing care to uninsured patients. (A more comprehensive discussion of the DSH program can be found on the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) website.[11]) A more important data point is how 340B is being used (and often abused) by non-DSH hospitals. Data suggest that hospitals that joined the program after 2004 are more likely to serve wealthier and insured populations.[12]

As Senator Grassley wrote to HRSA Administrator Wakefield, “HRSA needs to have an understanding of where 340B dollars are being reinvested to ensure that covered entities are fulfilling their mission. As the agency overseeing the 340B program, it is critical that you collect information from covered entities regarding their participation in the program given the level of revenue generated from participation.”[13]

This explosion of revenue for 340B institutions would hardly be problematic if there were also a simultaneous explosion in charity care programs to treat vulnerable patients. But the opposite scenario seems to be the case, as many charity care programs are declining. Shockingly, one study concluded that “it is evident that the ability of people suffering severe economic hardship to afford needed medicines and medical care, relative to the general population, is negatively correlated with growth in the 340B program.”[14]

Providers can accept 340B discounts regardless of whether they use the price reductions to help low-income or uninsured patients. A hospital can obtain an expensive medicine at a dramatically discounted rate, charge the patient’s insurer the full price, and pocket the difference.

Seventy-two percent of private nonprofit hospitals had a fair share deficit, meaning they spent less on charity care and community investment than they received in tax breaks. The combined fair share deficit for private nonprofit hospitals was $17 billion, with individual hospital deficits ranging from a few thousand dollars to $261 million.[15]

In 2013, the Charlotte Observer reported that Duke University Hospital purchased $65.8 million in drugs through the 340B program and saved $48.3 million. After selling the drugs to patients for $135.5 million, Duke was left with $69.7 million in profits.[16]

The ten hospitals with the largest fair share deficits accounted for more than 10% ($1.8 billion) of the nation’s total. These ten hospitals spend the least on charity care and community investment compared to the value of their tax exemptions.[17]

|

Name |

City |

Community Benefit Spending, % of Total Expenses |

Fair Share Deficit |

|

Cleveland Clinic |

Cleveland |

1.40% |

-$261 M |

|

New York-Presbyterian Hospital |

New York |

1.90% |

-$237 M |

|

UCSF Medical Center |

San Francisco |

0.90% |

-$208 M |

|

Massachusetts General Hospital |

Boston |

1.20% |

-$179 M |

|

University of Michigan Health System |

Ann Arbor |

1.10% |

-$169 M |

|

New York University Langone Medical Center |

New York |

2.50% |

-$163M |

|

Vanderbilt University Medical Center |

Nashville |

2.30% |

-$157 M |

|

Brigham and Women’s Hospital |

Boston |

1.00% |

-$142 M |

|

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania |

Philadelphia |

0.50% |

-$142 M |

|

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center |

Los Angeles |

1.60% |

-$138 M |

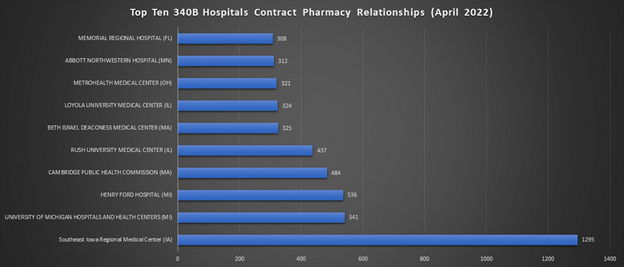

According to a report by the Berkeley Research Group (BRG), between 2013 and 2020 alone, hospitals established more than 94,600 new contract pharmacy arrangements through the 340B program, the BRG report finds. And according to a separate BRG study, the average profit margin of these pharmacies on commonly dispensed 340B drugs is an astounding 72%, compared to 22% for non-340B drugs.[18]

One particularly egregious example is Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare and Methodist Healthcare-Memphis Hospitals. According to an April 2022 press release from the Department of Justice U.S. Attorney’s Office, Middle District of Tennessee[19]:

“By purchasing West’s outpatient locations, Methodist was able to bill Medicare not only for the facility and professional components of outpatient treatment but also for the chemotherapy and other drugs provided, for which Methodist could recoup a staggering discount in costs through the 340B Discount Drug Program, resulting in $50 million in profits to Methodist in one year alone.”

The Contract Pharmacy Imbroglio

Hospitals and clinics aren’t the only ones using the program for financial gain. The government allows 340B participants without pharmacy services to distribute medicines to patients via third-party pharmacies known as contract pharmacies.[20] Until 2010, contract pharmacies were predominantly independently owned, local community pharmacies. The problem began in 2010 when the government said all 340B participants, even those with their own pharmacies, could contract with an unlimited number of third-party pharmacies.[21]

Over time, HRSA has introduced sub-regulatory guidance permitting covered entities to access 340B pricing through an unlimited number of contract (external) pharmacies. The most significant expansion came in 2010 when HRSA issued final guidance permitting covered entities to work with an unlimited number of contract pharmacies.[22]

In the ensuing years, for-profit pharmacies associated with the largest for-profit pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) rushed in to capitalize on the outsized margins available on 340B drugs. Between April 1, 2010 and April 1, 2020, the number of contract pharmacy arrangements increased by 4,228%[23] and now account for 28%[24] of 340B revenue. This might have been an acceptable trend had the increase in contract pharmacies been meant to reach underserved patient populations. That trend did not materialize.

According to a JAMA Health Forum study,[25] ever since more contract pharmacy relationships were allowed, the proportion of 340B contract pharmacies in socioeconomically disadvantaged and primarily minority neighborhoods declined, while they increased in affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods. This has allowed 340B hospitals and their for-profit contract pharmacies to expand their reach, charging fully insured patients steep markups and then pocketing the difference instead of passing on the savings.

Per an interesting article by Ted Okon (“Hospitals and for-profit PBMs are diverting billions in 340B savings from patients in need”),[26] “Some people want to paint the 340B contract pharmacy fight as big pharma versus little hospitals, but that view is willfully misleading. This battle is about a fundamentally broken program meant to help patients in need that is being exploited by hospitals and PBMs—some of the country’s most profitable corporations—to unjustly enrich themselves.”

PBMs have for years operated in the shadows of the convoluted U.S. drug supply chain without scrutiny, but there is an increasing understanding that these companies are anticompetitive monopolies out to pad their bottom lines rather than lower costs. Currently, three PBMs control around 80% of the prescription drug market in the United States and are among the most profitable corporations in the country.[27]

That’s why the Federal Trade Commission is investigating the industry[28] and why federal and state lawmakers are hurrying to promulgate new regulations to keep the most egregious PBM behaviors in check.[29]

According to a report in Drug Channels:

“By using external pharmacies, a 340B covered entity (CE) profits from prescriptions filled by a pharmacy that is not owned or operated by the covered entity. It does this after the prescription has been adjudicated and paid by such third-party payers as Medicare Part D and commercial health plans. (Medicaid prescriptions are excluded by statute. A significant number of Medicaid prescriptions dispensed at contract pharmacies also receive 340B discounts, a.k.a., the “duplicate discount” problem.)”[30]

Contract pharmacies can earn extraordinary profits from the fees paid by a 340B-qualified entity.[31]

Cui Bono? Cui Mato?

A patient with commercial or Medicare Part D insurance can’t detect that their prescription is eligible for 340B pricing. The pharmacist at the contract pharmacy can’t tell either. That’s because the determination is made weeks or months later. Consequently, the 340B covered entity requires insured patients to pay more for their prescriptions at contract pharmacies so the covered entity can generate 340B funds.[32]

Patients therefore don’t benefit from 340B discounts. Instead, they are expected to pay their health plans’ full out-of-pocket costs. Patients taking specialty and brand-name drugs often have out-of-pocket costs tied to coinsurance or within the deductible phase. They therefore pay full price—or a percentage of full price—for drugs that are sold to 340B hospitals at deep discounts. An insured patient could pay thousands of dollars out of pocket—even as the 340B hospital and its contract pharmacy generate substantial profits.

Medicare Part D patients also fund 340B savings. Like commercial plans, Medicare Part D plans often use percentage cost sharing instead of fixed dollar copayments for drugs on higher tiers. Furthermore, Medicare beneficiaries, unlike those in most private insurance plans, can face unlimited out-of-pocket prescription drug costs if they reach the catastrophic coverage limit. Consequently, a significant number of Medicare beneficiaries had very high levels of out-of-pocket spending. More than 1 million Part D enrollees had total drug spending above the catastrophic coverage threshold. They spent an average of $3,214 out of pocket.[33]

The 340B program has exploded to become the second-largest federal drug prescription program without helping the patients the program was intended to serve.[34] Instead, these “savings” have turned into big hospital “profits” obtained through slick arbitrage.

You read that right: it is possible for hospitals to use 340B profit to bolster their own bottom lines on the back of uninsured Americans. (Though it’s more common, and more lucrative, for hospitals to soak payers—commercial insurance companies, Medicaid, and Medicare—with marked-up claims for 340B-discounted medicines.)

According to the BRG study, 340B has become a significant source of undeserved revenue for hospitals and for-profit pharmacies gaming the system. When it comes to 340B, the “B” has, unfortunately, come to mean “Bottom line” and that bastardization of the original legislative intent cannot stand. As the BRG report reveals, the number of facilities participating in the 340B program grew by more than 30,900 between 2013 and 2020. Gross profits on 340B drugs, meanwhile, totaled more than $42 billion in 2020—a 12-fold increase over just seven years.[35] It’s a shameful “Show me the money” moment.

Why Rob Banks When You’ve Got 340B?

Willy Sutton, when asked why he robbed banks, answered, “Because that’s where the money is.”[36] It is, therefore, not surprising that contract pharmacies are following the same logic when it comes to engaging in the 340B program.

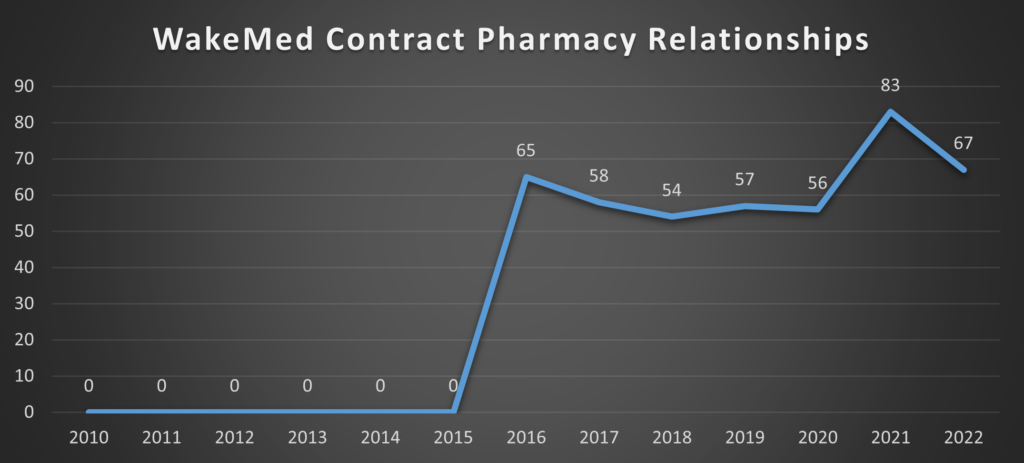

Since HRSA’s 2010 change in guidance, the number of contract pharmacy locations in the 340B program has skyrocketed:

The eligibility requirements are so loose that hospitals can take part in 340B even if they serve relatively few underprivileged patients. This has led to extraordinary growth in participation.

According to Drug Channels Institute’s latest analysis, an astonishing 32,000 pharmacy locations—more than half of the entire U.S. pharmacy industry—now act as contract pharmacies for the hospitals and other healthcare providers that participate in the 340B program. Over the past 12 months, the number of pharmacies in the program has grown by more than 2,000 locations.[37]

What’s more, five multi-billion-dollar, for-profit, publicly traded pharmacy chains and PBMs—CVS Health, Walgreens, Cigna (via Express Scripts), UnitedHealth Group (via OptumRx), and Walmart—account for three-quarters of all 340B contract pharmacy relationships with covered entities. Companies with retail pharmacies account for a majority of the 340B program’s total contract pharmacy locations. These companies include Walgreens, CVS Health, Walmart, Rite Aid, Kroger, and Albertsons.[38]

However, the number of locations provides a misleading picture of the 340B contract pharmacy marketplace. That’s because an individual contract pharmacy location can have relationships with multiple covered entities. A typical mail and specialty location operates as a 340B contract pharmacy for hundreds of covered entities. By contrast, a typical retail pharmacy location operates as a contract pharmacy for fewer than five covered entities.

The chart below shows the five largest contract pharmacy participants based on the total number of relationships with 340B covered entities. These companies are also among the largest U.S. pharmacies by prescription revenues.[39]

These data highlight the complex ways in which the 340B program interacts with the pharmacy and PBM industries:

- Walgreens and CVS Health remain the two most active 340B contract pharmacy participants. More than 90% of all Walgreens locations and more than three-quarters of all CVS locations are now 340B contract pharmacies.

- The two large PBMs that lack retail pharmacies—the Express Scripts business of Cigna and the OptumRx business of UnitedHealth Group—are among the most active participants when measured by the number of 340B contract pharmacy agreements with covered entities.

- These five companies are aligned with thousands of covered entities. For instance, Walgreens and CVS Health each are partnered with more than 2,500 covered entities. Express Scripts and OptumRx each work with more than 1,200 340B covered entities.

- The three largest PBMs—CVS Health, Express Scripts, and OptumRx—collectively have about 500 mail, specialty, and infusion pharmacy locations acting as 340B contract pharmacies. Combined, these locations have nearly 35,000 relationships with covered entities. Consequently, the big three PBMs’ non-retail pharmacies account for only 1.5% of 340B contract pharmacies—but 21% of 340B contract pharmacy relationships.

- Contract pharmacies earn 25% to 35% of total 340B discounts. For the top five contract pharmacy players, that translated into $3.2 billion in 2021 and a projected $2.9 billion in 2022.[40] But, these companies seem to share their 340B profits with plan sponsors by accepting lower reimbursement rates for preferred participation in narrow networks.[41] Nevertheless, only two of the largest companies, CVS Health[42] and Walgreens Boots Alliance,[43] have disclosed that changes to the 340B program could affect their profits.

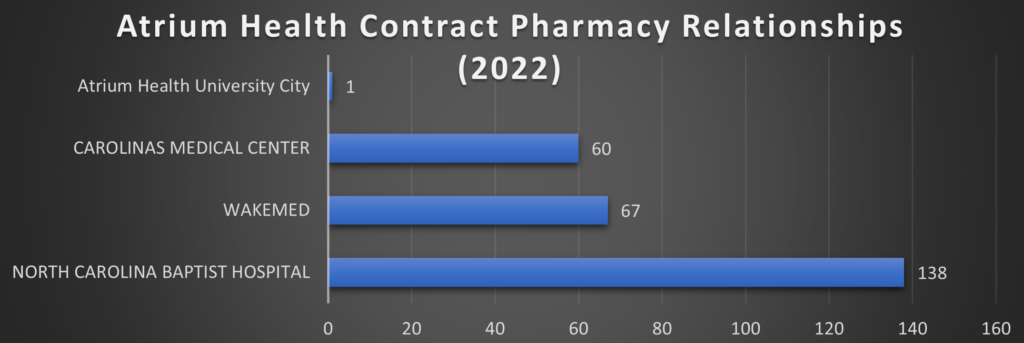

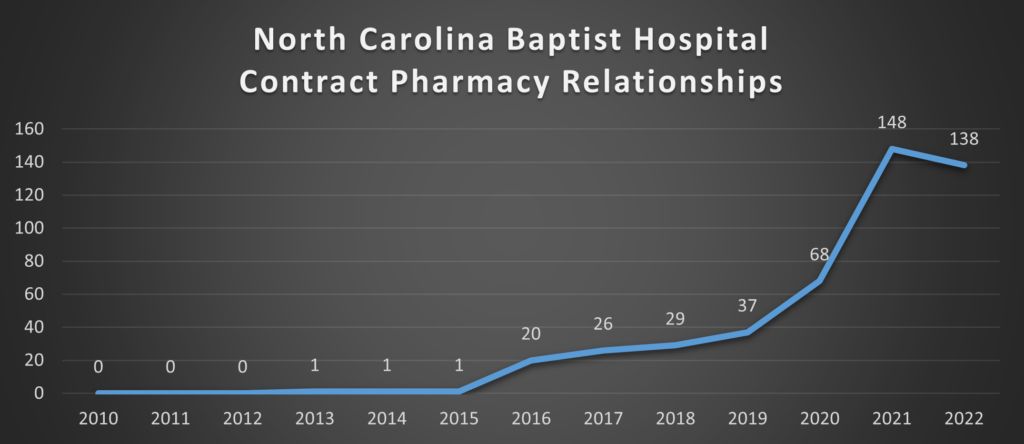

Tar Heels Feathering Their Own Nests

Once again, North Carolina serves as a cautionary study in miniature[44]:

Note: North Carolina Baptist Hospital is also DBA: Wake Forest Baptist, which was acquired by Atrium Health in 2020 for $3.4 Billion [www.atriumhealth.org]. Carolinas Medical Center is also DBA: Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center

This data can be retrieved from Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) Office of Pharmacy Affairs 340B OPAIS [https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/SearchLanding]. Maps are only examining Covered Entities’ Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) and their contract pharmacy relationships. Specialized Clinics [e.g., Comprehensive Hemophilia Treatment Centers (HM), Rural Referral Centers (RCC), or Tuberculosis Clinics (TB)] are not included in the analysis. HRSA OPAIS database is updated daily. The data in this analysis is current as of August 26, 2022.

Bottom line? The small amount of public information about the operation of 340B contract pharmacy arrangements paints a dismal picture for uninsured patients using hospitals’ 340B contract pharmacies.

- The Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that in a sample of 15 hospitals, 10 (67%) required uninsured patients to pay the full, non-340B price, even though hospitals were purchasing the drugs at the deeply discounted 340B price.[45]

- The GAO found that in a sample of 28 hospitals, 16 (57%) did not provide discounted drug prices to low-income, uninsured patients who filled prescriptions at the hospital’s 340B contract pharmacy.[46]

- The National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP), which sets electronic communication standards for pharmacy care, allows the identification of an individual prescription’s status under the 340B Drug Pricing Program.[47] However, hospitals and contract pharmacies have refused to utilize this voluntary standard.

Big PhRMA: Villain or Victim?

Eighteen biopharmaceutical manufacturers announced controversial policies related to covered entities’ contract pharmacies in the 340B Drug Pricing Program.[48] Specific policies vary by company, but most manufacturers require a covered entity to use an on-site pharmacy and/or designate a single, external contract pharmacy.[49] These restrictions appear to be having at least three primary effects:

- Hospitals are resetting their specialty pharmacy strategies. Hospitals and health systems have emerged as the fastest-growing participants in the specialty pharmacy market. In response to changes in manufacturers’ policies regarding external contract pharmacies, hospitals have accelerated their investments in in-house specialty pharmacy operations.

- PBMs are gaining 340B share. When forced to choose a single contract pharmacy partner, hospitals and health systems have been gravitating to the large PBM-owned specialty pharmacies that have access to drugs in limited dispensing networks. Consequently, PBMs are gaining a greater share of overall 340B contract pharmacy business, even as the overall contract pharmacy business shrinks.

- Some covered entities are considering sharing claims data. Manufacturers have offered to restore legacy contract pharmacy arrangements in exchange for 340B prescription claims data from covered entities. Few CEs have taken advantage of these opportunities. But recent court decisions suggest that the litigation has a long way to go—and may be resolved in the manufacturers’ favor.[50] The 340B Drug Pricing Program has become the second-largest government pharmaceutical program, based on net drug spending. But unlike such programs as Medicare Part D and Medicaid, 340B lacks a regulatory infrastructure, well-developed administrative controls, and clear legislation to guide the program.

The average profit margin for 340B drugs is 72%. In 2018 alone, hospitals and pharmacies together made $13 billion in 340B profits. The bulk of the pharmacy take goes to corporations like CVS. The hospitals and pharmacies split the profit. This arrangement proved so attractive that by 2020, hospitals had entered more than 109,000 contract arrangements with pharmacies to fill prescriptions under the program.[51]

In a recent analysis by the GAO, nearly half of 340B providers offered no discounts to any patients at their contract pharmacies.[52]

The initial goal of 340B—to help the most vulnerable patients afford medicine—remains as worthwhile as ever. Now that COVID-19 has upended the finances of millions of Americans, the program is even more essential.

Lawmakers and administration officials can make 340B work better for patients. Guard rails on which institutions can participate, plus better oversight, would ensure that only institutions doing charity work could get discounts, and that they directly benefit patients.

Such changes wouldn’t be difficult to implement, nor would they inspire much partisan controversy. But they would make an enormous difference for struggling Americans.

Case Study: 340B and HIV/AIDS: Replacing a “House of Cards” Approach

According to a June 2022 article in the New England Journal of Medicine, “Perverse Incentives—HIV Prevention and the 340B Drug,”[53] “[O]ver reliance on 340B to fund HIV-prevention services leaves many providers that are not 340B entities—or that are unable to navigate the complexity of 340B—with limited ways to finance the full array of PrEP (Pre-exposure prophylaxis) services for uninsured patients. These providers include smaller community-based programs that reach people who may not seek care at traditional clinics because of stigma or other structural barriers, such as patients from sexual or gender minority groups or people with substance use disorders. To be sure, by generating revenue for PrEP outreach and support programs, 340B has driven innovation in HIV prevention. But pockets of innovation—concentrated among well financed providers—do not translate into the easy-access approach to PrEP that’s needed to address widening disparities in use.”

“The most insidious effect of 340B, however, is the incentive it gives clinics to prescribe high-cost medications, even when effective and far cheaper options exist.” Further, “The complexity and size of the 340B program make it hard to adopt sweeping changes without destabilizing the entire system, but we believe policymakers should rethink this financing house of cards.”

And the authors offer some practical solutions:

“As envisioned in a recent proposal from Johns Hopkins University,[54] the federal government could negotiate fair prices for PrEP medications and laboratory services for uninsured people or Medicaid beneficiaries and could build and support a broad network of PrEP providers. Access to PrEP medications would be based on clinical evidence rather than the potential for revenue generation. Community-based organizations, many of which are not 340B entities and may not have a clinician on site, could be paired with telehealth providers to expand access.”

The PrEP access problem is caused by the greed of those who put their financial interests above those of the patients the 340B program was designed to protect. The solutions begin with recognizing that problem and addressing it directly and aggressively.

HRSA Inertia

While the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)—the government agency that oversees 340B—has refused to acknowledge that 340B is a dysfunctional program in need of reform, other government entities have rightly placed 340B in regulatory crosshairs:

- The influential and independent Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) recommended in 2016 that Medicare pay less for drugs administered by 340B entities,[55] arguing that the substantial profits going to these entities should be redirected to other avenues that would reduce patients’ costs.

- California (whose efforts were spearheaded by then Attorney General—now U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, Xavier Becerra)[56]—has spent years pushing back to reclaim lost rebates[57] to 340B entities since 2010, when HRSA altered the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program so that 340B entities can claim Medicaid rebates—their profits—over the states, substantially impacting state budgets.[58]

- New York Attorney General Letitia James has sued CVS for violating antitrust laws and hurting New York safety net hospitals and clinics that provide care for underserved communities across the state.[59] CVS required New York safety net hospitals and clinics to exclusively use a CVS-owned company, Wellpartner, to process and obtain federal subsidies on prescriptions filled at CVS pharmacies. CVS’s scheme forced safety net health care providers to incur millions in additional costs, while CVS continued to benefit through its subsidiary. The lawsuit alleges that CVS’s unfair business practice deprived safety net hospitals and clinics of critical federal funding that could have been used to improve and expand patient care. Through her lawsuit, Attorney General James is seeking to end CVS’s unfair and illegal practices and to recoup lost revenue for impacted safety net hospitals and clinics that would improve health care services. For years, CVS did not allow New York safety net hospitals and clinics to use the company of their choice to obtain subsidies on prescriptions filled at CVS pharmacies through the 340B federal program. community.[60]

- In his FY2022 budget, President Biden included a request to allow the federal government to audit a 340B covered entity’s records to determine how profits generated from the program are being used.[61]

Advancing 340B: Don’t Fix the Blame, Fix the Problem

According to a 2020 letter sent by Drug Channels Institute’s Adam Fein to Senator Lamar Alexander (then the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions) and Representative Greg Walden (then the Republican Leader of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce) detailing the many issues relating to the 340B program, “good intentions have been overwhelmed by middlemen that pocket discounts while forcing patients, employers, and the Medicare program to pay more for prescription drugs. The unmanaged and unregulated growth of contract pharmacies is also causing significant channel distortions within the U.S. pharmaceutical distribution and reimbursement system.”[62]

Rather than simply restating the problem, Fein offers specific recommendations that would return the 340B program to its original congressional intent. Specifically:

- Mandate that contract pharmacies for 340B covered entities charge no more than the discounted 340B price to uninsured, underinsured, and vulnerable patients. There is simply no excuse for overcharging needy patients, per the situations documented by the OIG and GAO.

- Require that contract pharmacy fees be based on fair market value standards. This would prevent for-profit pharmacies from capturing 340B discounts. It would also protect smaller covered entities that lack negotiating clout with the larger 340B contract pharmacy providers.

- Revise hospital eligibility for the 340B program to create a clearer patient definition. Most prescriptions at 340B contract pharmacies are dispensed to patients with commercial and Medicare Part D insurance. The program should be updated to target benefits towards needy patients and true safety net providers.

- Limit the number and geographic scope of contract pharmacy arrangements. Covered entities are not required to justify large networks based on access needs for vulnerable populations. Smaller, more controlled networks will ensure that only eligible patients use the contract pharmacy.

- Require greater transparency into profits generated by 340B contract pharmacies. Such a requirement would ensure that discounts provided under the 340B program are being utilized appropriately. There is compelling evidence that hospitals are double counting 340B savings against their fundamental legal and statutory community benefit obligations as non-profit organizations.

- Require contract pharmacies to identify 340B prescriptions at the time of adjudication (payer prescription approval). This change would make manufacturers more willing to offer larger rebates to third-party payers.

Net/Net, the unregulated growth of 340B through dubious means is drawing attention and corrective action from different federal and state level authorities. It’s about time.

According to a 2018 report by the House Energy & Commerce Committee (E&C),

“Congress did not clearly identify the intent of the program and did not identify clear

parameters, leaving the statute silent on many important program requirements. According to

the 1992 House Report accompanying the legislation, the 340B program was intended ‘to enable [covered] entities to stretch scarce Federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.’ It is unclear whether Congress intended low-income and uninsured individuals to directly benefit from the reduced drug prices offered under the 340B program. Congress should clarify the intent of the 340B program and, in doing so, evaluate how developments in the health care landscape over the past 25 years have affected, if at all, the structure and goals of the 340B program.”[63]

The E&C report offers its own recommendations[64]:

- “HRSA should soon finalize and begin enforcing regulations in each of the three areas in

which it currently has regulatory authority, including the 340B Alternative Dispute

Resolution process, the imposition of civil monetary penalties against manufacturers that knowingly and intentionally overcharge a covered entity for a 340B drug, and the

calculation of ceiling prices. - Congress should give HRSA sufficient regulatory authority to adequately administer and oversee the 340B program, including the ability to improve program integrity, clarify program requirements, monitor, and track program use, and ensure that low-income and uninsured patients directly benefit from the 340B program.

- Congress should require certain covered entities to conduct independent audits of

program compliance and should determine what such audits should assess and evaluate. - All covered entities should perform independent audits of their contract pharmacies at regular intervals to ensure 340B program compliance.

- Congress should equip HRSA with more resources and staff to conduct more rigorous

oversight and more effective management of the 340B program. - Congress (and HHS to the degree possible) should take steps to identify and reduce

duplicate discounts for drugs paid for under Medicaid managed care. - Congress should evaluate whether the permissible scope of HRSA’s audits should be

expanded to cover other features of the program. - HRSA should work toward ensuring that it audits covered entities and manufacturers at the same rate.

- Congress should clarify the intent of the 340B program to ensure that HRSA administers and oversees the 340B program in a way that is consistent with that intent. In doing so, Congress also should evaluate how developments in the health care landscape over the past 25 years have affected, if at all, the structure, and goals of the 340B program.

- Congress (or HRSA where HRSA already has authority to make such changes) should

promote transparency in the 340B program, including ensuring that covered entities and other relevant stakeholders have access to ceiling prices and requiring covered entities to disclose information about annual 340B program savings and/or revenue. - Congress should establish a mechanism to monitor the level of charity care provided by covered entities. This should include a clear definition of charity care such that the data can be used to fairly compare care provided across entities.

- Congress should reassess whether DSH is an appropriate measure for program eligibility, or whether a metric based on outpatient population would be more appropriate.”

Concluding Thoughts: Regaining Control of the Runaway Train

Piecemeal actions won’t fix a 340B system run amok. Until Congress musters the will to hold the covered entities profiting from 340B accountable, our most vulnerable patients will lose out on the deep 340B discounts meant for them, while profit-seekers continue to pocket these discounts for their own gain.

Congress can start to correct 340B’s course by insisting on the necessary oversight and implementing the overdue reforms that will restore benefits to patients while protecting the public from rampant waste and abuse.

Today, just as when 340B began in 1992, far too many Americans are having a hard time paying for medicines and need help. Yet 340B has not fulfilled its promise to help low income and uninsured patients access outpatient medicines. It’s time for lawmakers to put an end to this corruption of legislative intent and enact meaningful reforms that ensure the program offers a genuine lifeline for patients who need it most.

Author’s Note

I believe it is important to note that HRSA repeatedly first ignored and then denied requests to interview current HRSA Administrator, Carole Johnson on the 340B issues discussed in this paper.

[1] https://www.ajmc.com/view/340b-drug-pricing-program-and-hospital-provision-of-uncompensated-care

[2] https://www.drugchannels.net/2021/06/exclusive-340b-program-soared-to-38.html

[3] https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/

[4] https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/08/the-340b-program-climbed-to-44-billion.html

[5] https://revcycleintelligence.com/news/340b-dsh-hospitals-provided-41b-in-uncompensated-care-in-2020

[6] https://www.340bhealth.org/files/Dobson_DaVanzo_Op_Margins_and_UC_FINAL.pdf

[7] https://www.drugchannels.net/2020/07/how-hospitals-and-pbms-profitand.html

[8] https://www.grassley.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2013-03-27-CEG-to-HRSA-340B-Oversight-3.pdf

[9] Id.

[10] https://www.shpnc.org/media/2604/open

[11] https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/eligibility-and-registration/hospitals/disproportionate-share-hospitals

[12] https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/article/federal-340b-drug-pricing-policies-need-reform-to-realize-potential/

[13] https://www.grassley.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2013-03-27-CEG-to-HRSA-340B-Oversight-3.pdf

[14] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3284078

[15] https://lownhospitalsindex.org/2022-fair-share-spending/

[16] https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/healthcare/do-hospitals-profit-from-drug-discounts-meant-for-poor-uninsured-patients

[17] https://lownhospitalsindex.org/2021-winning-hospitals-community-benefit/

[18] https://media.thinkbrg.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/06150726/BRG-ForProfitPharmacyParticipation340B_2020.pdf

[19] https://www.justice.gov/usao-mdtn/pr/united-states-files-suit-against-methodist-le-bonheur-healthcare-and-methodist

[20] https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/implementation-contract

[21] https://www.statnews.com/2022/07/07/for-profit-pbms-diverting-billions-340b-savings/

[22] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2010-03-05/pdf/2010-4755.pdf

[23] https://media.thinkbrg.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/06150726/BRG-ForProfitPharmacyParticipation340B_2020.pdf

[24] https://www.statnews.com/pharmalot/2022/05/16/hhs-340b-hospitals-prescription-drugs/

[25] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2793530

[26] https://www.statnews.com/2022/07/07/for-profit-pbms-diverting-billions-340b-savings/

[27] https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/ftc-launches-investigation-into-pbms-cvs-unitedhealth-cigna-and-more-hit/625058/

[28] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/06/ftc-launches-inquiry-prescription-drug-middlemen-industry

[29] https://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/grassley-cantwell-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-combat-rising-prescription-drug-prices-and-provide-more-transparency

[30] https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/07/exclusive-five-pharmacies-and-pbms.html

[31] 2022 Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers.

[32] http://drugchannelsinstitute.com/files/AdamFein-DrugChannels-340B-30Oct2020.pdf

[33] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/millions-of-medicare-part-d-enrollees-have-had-out-of-pocket-drug-spending-above-the-catastrophic-threshold-over-time/

[34] https://www.thinkbrg.com/insights/publications/measuring-relative-size-340b-program-2020-update/

[35] https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/the-340b-drug-pricing-program-background-ongoing-challenges-and-recent-developments/

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willie_Sutton

[37] https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/07/exclusive-five-pharmacies-and-pbms.html

[38] Ibid

[39] https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/03/the-top-15-us-pharmacies-of-2021-market.html

[40] https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/04/drug-channels-news-roundup-april-2022.html

[41] https://drugchannelsinstitute.com/products/industry_report/pharmacy/

[42] https://twitter.com/DrugChannels/status/1491581442899521541

[43] https://twitter.com/DrugChannels/status/1448985789912727570

[44] This data can be retrieved from Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) Office of Pharmacy Affairs 340B OPAIS [https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/SearchLanding]. Maps are only examining Covered Entities’ Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) and their contract pharmacy relationships. Specialized Clinics [e.g., Comprehensive Hemophilia Treatment Centers (HM), Rural Referral Centers (RCC), or Tuberculosis Clinics (TB)] are not included in the analysis. HRSA OPAIS database is updated daily. The data in this analysis is current as of August 26, 2022.

[45] https://oig.hhs.gov/newsroom/oig-podcasts/contract-pharmacy-arrangements-in-the-340b-drug-discount-program/

[46] https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-480

[47] https://www.ncpdp.org/NCPDP/media/pdf/340B_Information_Exchange_Reference_Guide.pdf

[48] https://www.drugchannels.net/2022/07/exclusive-five-pharmacies-and-pbms.html

[49] https://www.amerisourcebergen.com/provider-solutions/340b-advisory-services/340b-manufacturer-updates

[50] https://www.linkedin.com/posts/adamjfein_340b-pharmacy-notalawyer-activity-6943171924617310208-X3KQ/

[51] https://www.thinkbrg.com/insights/publications/for-profit-pharmacy-participation-340b/

[52] https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-107.pdf

[53] Julia L. Marcus, Amy Killelea & Douglas S. Krakower, Perverse Incentives—HIV Prevention and the 340B Drug Pricing Program, 386 New Eng. J. Med. 2064–66 (2022), https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2200601.

[54] New Policy Proposal Seeks to Improve Access to Medications That Prevent HIV Infection, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health., January 2022, https://publichealth.jhu.edu/departments/health-policy-and-management/research-and-practice/new-policy-proposal-seeks-to-improve-access-to-medications-that-prevent-hiv-infection.

[55] https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/import_data/scrape_files/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-3-hospital-inpatient-and-outpatient-services-march-2016-report-.pdf

[56] https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/attorney-general-becerra-announces-189-million-california-settlement-memorial

[57] https://oag.ca.gov/news/press-releases/attorney-general-becerra-announces-189-million-california-settlement-memorial

[58] https://www.cityandstateny.com/policy/2021/04/whats-in-store-for-new-york-nonprofits-in-the-state-budget/182983/

[59] https://ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/ny_v._cvs_summons_complaint.pdf

[60] https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/2022/attorney-general-james-sues-cvs-harming-new-york-safety-net-hospitals-and-clinics

[61] https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/hospitals/from-340b-to-a-public-option-4-healthcare-items-you-may-have-missed-biden-s-budget

[62] http://drugchannelsinstitute.com/files/AdamFein-DrugChannels-340B-30Oct2020.pdf

[63] https://republicans-energycommerce.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/20180110Review_of_the_340B_Drug_Pricing_Program.pdf

[64] Id.

Update Magazine

Fall 2022

PETER J. PITTS is President of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest and a Visiting Professor at the University of Paris School of Medicine. He is a former FDA Associate Commissioner and member of the United States Senior Executive Service.

PETER J. PITTS is President of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest and a Visiting Professor at the University of Paris School of Medicine. He is a former FDA Associate Commissioner and member of the United States Senior Executive Service.