What’s Missing from MDUFA IV?

Vol. 6, Issue 4 // October 31, 2016 By Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein, MD

When passed by Congress in 2002, the Medical Device User Fee Modernization Act (MDUFMA) established mechanisms by which industry would pay FDA fees to improve the speed and efficiency of the work of the agency.1Every five years since, industry and FDA negotiate the fees and their use for continuing operational improvements, as well as the metrics to judge program impact, which are then formalized by Congress through the Medical Device User Fee Amendments legislation (MDUFA). Although user fees support a minority of regulatory needs, the amounts are substantial. Based on the proposed 2017 budget for FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), ~$138 MM (~30% of CDRH’s total budget) in industry-paid user fees would supplement the congressionally allocated budget of ~$326 MM (~70%).2 The parties recently completed negotiations for 2018-22, which will be sent to Congress to enact as MDUFA IV.3

I. Effects of MDUFA on CDRH Performance

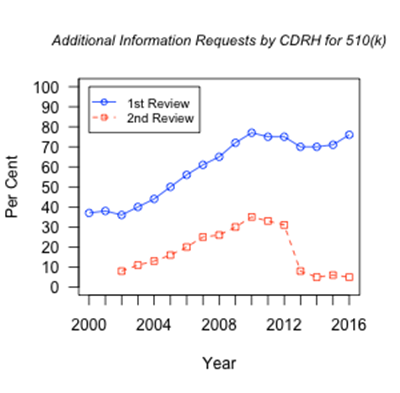

The first three cycles of MDUFA moved the regulatory landscape to a higher quality of execution in FDA’s processing of regulatory filings.4,5 Specifically, with progressively more difficult metrics in place, CDRH produced progressively better results.2 The goals do not include reducing regulatory requirements for a product to reach the market—this is not about making that easier. Instead, the process focuses on more efficient exchange of information between industry and the agency in order to get to the right decision more quickly and efficiently. Judging the impact of the user fee program is complex. For example, FDA’s responsibilities under each of the MDUFA cycles included increasing the percentage of decisions reached within a designated time period. For example, the agency needed to make decisions on the most complex devices, Class III—Premarket Approval (PMA), within 180 days for at least 80% of the applications in 2015; this objective was achieved. Note that the 180-day target refers to the number of days under FDA review, as opposed to the time required by the applicant to respond to FDA requests/feedback, during which time the “FDA clock” freezes. In the final year of MDUFA I the target was 50% within 180 FDA days and increased to 60% at the end of MDUFA II. In 2016 the target is 90%. However, along with this success, the average time FDA spent on the review of these devices has not changed significantly since 2000 (mean ± SE = 239 ± 10, p= 0.46 by Pearson product-moment correlation).6 The percentage of decisions within 90 FDA-days for the 510(k) program (Class II—moderate risk) was targeted to be at least 80% by end of MDUFA I, at least 90% by the end of MDUFA II and up to 95% by end of MDUFA III. In 2015, decisions were reached for 97% of applications within 90 days. However, similar to the PMA program, the average number of FDA days to reach decisions is stable since 2000 (mean ± SE = 71 ± 2, p= 0.75 by Pearson product-moment correlation).6 In this context, the agency and industry agreed that increased personnel should be supported by MDUFA IV.3 Review of FDA performance shows consistent emphasis on transparent and useful communication. In the 510(k) program, agency review resulted in nearly doubling in frequency of requests for additional information from the applicant on the initial review since the beginning of MDUFA (from 37% to over 70%). Metrics show that this increase in scrutiny is paralleled by a marked drop in requests for additional information during the second cycle of FDA review, particularly during MDUFA III. (See Figure1).6 The agency appears to be faster and more efficient at identifying the critical decision-making matters. Figure 1. Requests by FDA for Additional Information to 510(k) applicants on 1st and 2nd review cycles.6

Another mechanism for communication between applicants and FDA is the pre-submission process, wherein applicants can engage early and frequently while designing their product and their development plan. The number of these interactions is increasing. One bottleneck faced by applicants is the initiation of clinical trials, and here the agency is quicker to approve such applications. A focus during MDUFA III, the number of such Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) applications approved within two cycles of review climbed from 15% to 75%, and median days to approval dropped from 442 to 30 from 2011 to 2015.2 As with the pre-submission program, the impact will become apparent over the coming years as these products/programs advance through development, though both appear favorable in the context of MDUFA goals. Table 1. The plan for advancing innovative medical devices.Although these metrics suggest significant advances in the approval process, prior MDUFA legislation did not provide funds or authorities to meaningfully advance CDRH’s speed or efficiency in its regulation of innovative, cutting-edge technologies. To fill that gap, CDRH launched its Innovation Initiative without explicit congressional support, and with progressively less visible impact than evident from the funded initiatives.7 Thus, the Innovation Initiative launched in 2011 as an outwardly facing experiment to learn how to engage with novel technology/product development funded by the Defense Advanced Research Products Agency (DARPA). It was also the part of the initial White House sponsored Entrepreneurs-in-Residence program. However, the Initiative eventually evolved into a review of product labeling with little interaction with industry, practitioners, or patients.8 Appropriate incentives and support for expediting innovation are still an under-addressed aspect of the medical device regulatory review process. The recently completed MDUFA IV negotiations cannot be considered successful without including direct and meaningful support for CDRH to foster innovation in pursuit of improving public health. Congress could consider the following approaches to supplement the current proposal.3

II. A Plan to Advance Innovative Medical Devices

Over recent years, FDA’s focus on the hurdles facing medical device developers led to the launch of several important tools and processes, including the modified pre-submission procedures, the expedited review process, the breakthrough product pathway, the early feasibility study guidance, and others within the Innovation Initiative. These tools provide a foundation upon which the Center can transform its processes and leverage its culture to move products efficiently into clinical trials, to clarify evidence required to enter the market, and to deploy devices widely to impact public health, under the conditions where scientific evidence supports each. A four-point plan can make these goals achievable.

First, the innovators within FDA must be empowered to coalesce into teams. When CDRH launched the Entrepreneurs-in-Residence program, it put in place a team of cross-trained, intellectually curious, motivated regulators, and learned that such characteristics are relatively common—though not typically celebrated—within the Center. MDUFA legislation can make this an obligation for the Center. Thus, by finding, insulating, legitimizing, and empowering these engineers, clinicians, scientists, and policy experts to act autonomously to identify and tackle key issues, the Center will be positioned to contribute to innovations to impact public health. This approach works when the teams are provided with sufficient autonomy to insulate them and their work from the organization’s commitment to the status quo.9 Second, the Center should reorganize to harmonize the cultures of different technology areas with the capacities of individual reviewers. For example, there is a significant difference between the demands on reviewers charged with regulation of surgical tools as compared to regulation of cerebral implants for restoring function to quadriplegics. The former relies upon Standards and Guidance documents—allowing for a different set of skills and different level of intellectual risk for a reviewer than the latter. In the cerebral implants case, there are neither direct precedents for such products, nor command of the questions that will certainly arise during product development—and which cannot be predicted. Presumably, a new reviewer typically would be better for the surgical tools case. And an experienced reviewer who is capable of and comfortable with problems of clinical and scientific uncertainty would be best suited to review the cerebral implants. In addition to traditional means of rewarding reviewers’ performance, perhaps user fees could provide incentives and rewards for those reviewers who are appropriate for and willing to move from the former to the latter. Third, the user fee negotiations should include placing a burden on Congress to fix the reimbursement processes for new medical devices. Currently, the process starts upon clearance or approval of a medical device, at which point an application is made to the American Medical Association—and for some types of devices there is an annual deadline for submission.10 After several months, a code may be approved, at which point a physician/facility can bill for the procedure and device. Without that code, revenue does not flow, which means an innovative, high impact device may not be used because no one can pay for it. Twelve to 18 months can pass from device approval to publication of a billing code. When MDUFMA was passed in 2002, its purpose was to speed the delivery of devices to market (where appropriate), which is critical to improvement of the public health. However, without a payment or reimbursement mechanism, manufacturers cannot afford to produce and doctors/facilities cannot afford to use innovative technology. Thus, Congress must act in recognition of this barrier to the clinical uptake of new devices by enacting new law to require billing codes to be generated at the time of device approval/clearance—perhaps automatically—so that “patients may enjoy the benefits of devices to diagnose, treat, and prevent disease,” which was the stated intent of MDUFMA.1 Fourth, for new programs, CDRH should employ a “pick the winner” strategy. In such an approach, within a finite period of time (e.g., six-18 months) the Center would commit to a subset of active projects that show greatest progress and promise for impact on public health, with a focus on the most innovative, the potential game-changers. The other projects would cease, and funds initially projected for them would be applied to the winning programs or be used to launch new projects. This approach relies on internal competition and recognition of the finite nature of resources as motivators for excellence.III. Conclusions

From its inception, the purpose of user fees legislation was to assure that patients would “enjoy the benefits” of medical devices promptly.1 And for incremental improvements to existing technology, FDA’s CDRH is now a more efficient organization, with excellence in execution of standard processes. However, incremental improvements to devices are not the path to transformative impact on public health—which is possible with new, innovative devices. This four-part plan serves as a template for recalibrating the medical device development and regulatory landscape, in accordance with the intent of MDUFMA and for the benefit of public health. With the medical device user fee negotiations advancing towards conclusion, adoption of such a plan represents a critical public health need, and without doing so, the system will be stuck with its focus on incrementally optimizing the efficiency of its assembly line, without the mandate, authority, or resources necessary to transform the landscape, and thereby, public health.

References

- 107th Congress of the United States of America. Medical Device User Fee and Modernization Act (MDUFMA). HR 5651. 2002:1-33. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-107hr5651enr/pdf/BILLS-107hr5651enr.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Office of the Commissioner FDA. 2017 FDA Justification of Estimates of Appropriations Committees.; 2016. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/ReportsManualsForms/Reports/BudgetReports/UCM488557.pdf.

- Office of the Commissioner FDA. FDA – Industry MDUFA IV Reauthorization Meeting Minutes August 15, 2016. 2016:1-7.

- Shuren J. MDUFMA: Congressional Testimony before Committee on Energy and Commerce. 2007. http://www.hhs.gov/asl/testify/2007/05/t20070516a.html. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Office of Planning FDA Office of the Commissioner. FDA-Track CDRH Dashboard. 2016. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/Transparency/track/ucm203038.htm. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Office of the Center Director FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. 3rd Quarter FY2016 MDUFA III Performance Report.; 2016. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/MedicalDeviceUserFee/UCM519548.pdf.

- Office of the Center Director FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Innovation Pathway. 2011. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDRH/CDRHInnovation/InnovationPathway/default.htm. Accessed October 5, 2016.

- Office of the Center Director FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Entrepreneurs in Residence Program. 2015. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDRH/CDRHInnovation/ucm456456.htm. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- Christensen CM. The Innovator’s Dilemma. When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press; 1997.

- CPT Editorial Panel American Medical Association. CPT Process – How a Code Becomes a Code. 2016. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/solutions-managing-your-practice/coding-billing-insurance/cpt/cpt-process-faq/code-becomes-cpt.page. Accessed May 24, 2016.

About the Author: Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein is Founder/CEO of SRD Med, LLC, and currently is developing innovative medical devices under FDA regulations. He formerly served as Associate Center Director for Technology and Innovation at FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiologic Health where he led the team that launched its Innovation Initiative and the White House’s first Entrepreneurs-in-Residence program. In addition, Jonathan Sackner-Bernstein serves as a consultant to DARPA to assist with its regulatory and commercialization processes, which include FDA strategy/tactics.

The views, opinions, and statements expressed in this article are those of the author(s). FDLI neither contributes to nor endorses Forum articles.

Food and Drug Policy Forum

Volume 6