From Secret Tests to Therapy Trials: MDMA’s Long Road to Legitimacy

By Karl Nobert, Chelsea DeLeon, Bernard A. Brown, Justin May, & David DiGiacomo

First synthesized in 1912, MDMA’s history is long and varied. In the 1940s, the U.S. Army conducted classified MDMA tests as part of its chemical warfare research program, while the 1970s saw it being introduced to psychotherapy.[1] The drug’s success among patients—reducing their fear response and facilitating emotional breakthroughs—led to increased recreational use in the 1980s.

While therapists and psychiatrists advocated for MDMA’s continued legal status due to its perceived therapeutic benefits, in 1984 the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classified MDMA as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act, effectively ending its legal medical use.[2]

Three decades later, MDMA is still making headlines. On Friday, August 9, 2024, Lykos Therapeutics received notification from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that its New Drug Application (NDA) for MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD had not been approved.[3] According to the statement released by Lykos Therapeutics, FDA requested further studies to evaluate the treatment’s safety and efficacy. Lykos Therapeutics also noted the issues raised in the decision by FDA echoed the concerns raised during the Psychopharmacologic Drug Advisory Committee meeting held on June 4, 2024. To understand how FDA arrived at its decision, it is important to take into consideration 1) the regulatory history between Lykos Therapeutics and FDA; 2) the clinical data provided by Lykos Therapeutics in support of its New Drug Application to FDA; and 3) the key issues expressed by the Advisory Committee and FDA during the June 4th, 2024 Advisory Committee hearing.[4]

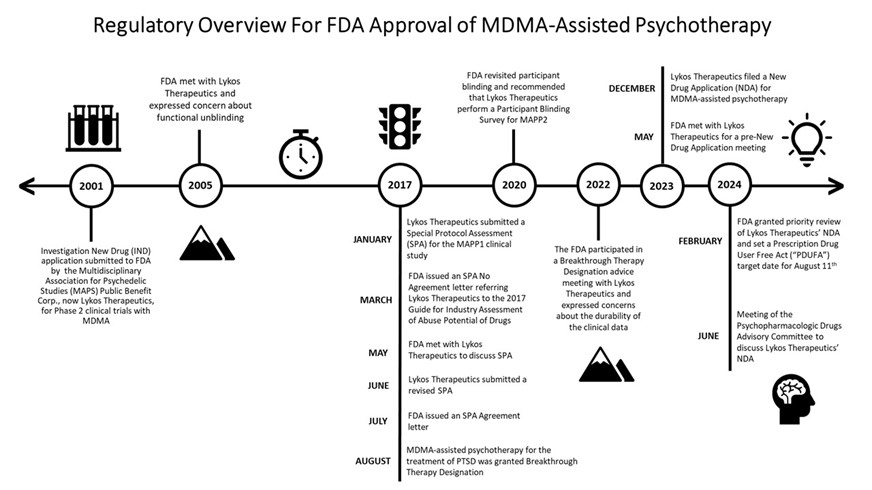

The Regulatory History of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy

During the Advisory Committee hearing, FDA provided a summary of the regulatory history between Lykos Therapeutics and FDA concerning MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.[5] The FDA’s interaction with Lykos Therapeutics is summarized below.

In 2001, an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) was submitted to FDA for the use of MDMA in human subjects by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) Public Benefit Corp., now Lykos Therapeutics. In response to the information presented in the IND, FDA allowed Phase 2 clinical trials with MDMA to proceed in humans. Four years later, FDA met with Lykos Therapeutics and expressed concerns about functional unblinding, due to MDMA’s ability to alter mood and perception. Due to MDMA’s ability to induce physiological effects, FDA suggested that Lykos Therapeutics include an additional control group where patients received an active comparator drug, such as niacin or low-dose MDMA. In response, Lykos Therapeutics suggested that an active comparator, such as niacin or low-dose MDMA, could worsen PTSD symptoms or anxiety in patients. Ultimately, FDA and Lykos Therapeutics did not reach an agreement regarding a protocol to mitigate functional unblinding.

In January 2017, Lykos Therapeutics submitted a protocol for the MAPP1 clinical study as a Special Protocol Assessment (SPA). In March 2017, FDA issued a SPA – No Agreement letter based upon the agency’s disagreement with the proposed statistical analyses and choice of secondary end point to assess the effectiveness of the results in the study. The letter indicated that “[f]or all Phase 1, 2, and 3 studies, AEs [adverse events] associated with potential abuse or overdose must be documented” and FDA referred Lykos Therapeutics to its 2017 guidance for industry, “Assessment of Abuse Potential of Drugs.”[6] By May 2017, a meeting was held to discuss FDA’s rejection of the protocols submitted by Lykos Therapeutics under the SPA. In June and July 2017, a revised SPA request was submitted by Lykos Therapeutics, and FDA issued a SPA Agreement letter. Even though a SPA Agreement allows the clinical trial to proceed, FDA was clear that a SPA Agreement letter does not guarantee that clinical trial results will support approval.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD was granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation in August 2017. Just over two years later, in October 2020, FDA revisited participant blinding and recommended that Lykos Therapeutics perform a Participant Blinding Survey for MAPP2. Lykos Therapeutics participated in a Breakthrough Therapy Designation advice meeting with FDA in September 2022. During the meeting, FDA expressed concerns related to the durability of the treatment effects in response to MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.

In May 2023, Lykos Therapeutics met with FDA for a pre-NDA meeting. The following December (2023), Lykos Therapeutics filed an NDA for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Shortly thereafter, FDA accepted and granted prior review status of the application, setting a Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) target action date of August 11, 2024. The Psychopharmacologic Drug Advisory Committee conducted a hearing on June 4, 2024 to discuss clinical data collected by Lykos Therapeutics in support of their application for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.[7] After nearly a full day of discussion, Advisory Committee members were asked to vote on the following questions:

- Does the available data show that the drug is effective in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder?

- Do the benefits of midomafetamine, with FDA’s proposed risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS), outweigh its risks for the treatment of patients with PTSD?

In a 2–9 vote, the committee members voted against the effectiveness of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.[8] Similarly, the committee members voted 1–10 rejecting the notion that the benefits of MDMA with FDA’s proposed REMS outweighed the risk for treatment of patients with PTSD.

Clinical Research Made Available to Advisory Committee and FDA

Lykos Therapeutics provided the Advisory Committee and FDA with the results obtained from three Phase 3 clinical trials in humans: a multi-site phase 3 study of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD 1 (MAPP1), a multi-site phase 3 study of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD 2 (MAPP2), and a long-term safety and effectiveness study of MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of PTSD (MPLONG). A non-exhaustive summary of MAPP1, MAPP2, MPLONG, and results are provided below.

MAPP1/MAPP2

MAPP1 and MAPP2 were both randomized, placebo-controlled, 18-week studies. MAPP1 included participants with severe PTSD, whereas MAPP2 included participants exhibiting both moderate and severe PTSD. [9] The severity of PTSD was assessed using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5).

Both MAPP1 and MAPP2 included preparatory sessions, medication sessions, and integrative sessions. During the preparatory sessions study participants underwent psychoeducation to help prepare for the medication session. Study participants in both MAPP1 and MAPP2 discontinued any psychiatric medications during the preparatory sessions. Following the preparatory sessions, participants received either MDMA (treatment) or placebo (control) in a medical setting and received psychotherapy by a trained, licensed professional following guidance provided by the “MAPS Manual for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder” (referred to herein as the MAPS Manual).[10] The medication session was followed by weekly integrative therapy sessions for three weeks. Following the three weeks of weekly integrative therapy sessions, study participants received their assigned treatment in a subsequent medication session. Participants received a total of three medication sessions followed by three integrative sessions.

Study participants were evaluated for their improvement in CAPS-5 rating. CAPS-5 ratings were completed by independent raters possessing graduate-level training is psychology, social work, or counseling with at least one year of experience working with a trauma-exposed population. No independent rater assessed the same participant more than once.

MPLONG

MPLONG was an exploratory observational study that did not involve any treatment protocol. Participation in MPLONG occurred at least six months after participation in either MAPP1 or MAPP2. MPLONG consisted of a single follow-up visit. There was no time standardization for participant’s engagement in the MPLONG study.

MAPP1, MAPP2, MPLONG Study Results

Both MAPP1 and MAPP2 showed a statistically significant improvement in the CAPS-5 primary endpoint at the end of the study (week 18) for study participants receiving MDMA as compared to the placebo group.[11] Participants in both MAPP1 and MAPP2 showed on average a 24-point change in CAPS-5 rating in response to MDMA and the prescribed psychotherapy. Interestingly, participants who received placebo experienced a 13- to 14-point mean change in response to the psychotherapy itself. FDA and Lykos Therapeutics had previously agreed that a 10-point change or greater on the CAPS-5 rating would represent a clinically meaningful change in the patient. These results indicate study participants receiving either MDMA-assisted psychotherapy or placebo-psychotherapy experienced a clinically meaningful change in their CAPS-5 rating. In addition to the results from MAPP1 and MAPP2, Lykos Therapeutics has interpreted that data collected during MPLONG showed improvement of CAPS-5 rating in MDMA receiving patients that persisted at and beyond six months.[12]

Key Issues Identified by the Advisory Committee and FDA

During the June 4, 2024 hearing, the Advisory Committee and FDA raised several issues with Lykos Therapeutics. The keys issues identified by the Advisory Committee and FDA are summarized below. Materials from the Advisory Committee hearing are publicly available.[13]

FDA Does Not Regulate Psychotherapy

FDA made clear during the Advisory Committing hearing that it does not and cannot regulate the practice of psychotherapy, but it can indicate that a drug, such as MDMA, is used only in conjunction with a specific treatment modality, such as psychotherapy.[14] This presents a particular challenge for the MDMA-assisted psychotherapy because psychotherapy is a significant component of the treatment regimen.

Collectively, FDA and the Advisory Committee expressed concerns regarding the standardization of psychotherapy. The Advisory Committee noted that the MAPS Manual allows for flexibility and may produce a varying degree of variability in the psychotherapy provided by individual therapy providers.[15] The variability allotted by the MAPS Manual was cited by the Advisory Committee and FDA as a hardship in assessing the effectiveness of the data obtained during the study.[16] Concerns related to the variability were magnified by the absence of data comparing the effects of MDMA-alone without psychological intervention and the lack of data comparing MAP Manual therapy to other psychotherapeutic inventions.[17]

The Advisory Committee also expressed concerns about the vulnerable state that patients may enter when receiving MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.[18] This concern was amplified by reports of sexual assault and sexual misconduct during Lykos Therapeutics’ Phase 3 clinical trials.[19]

Functional Unblinding

Prior to the submission of an NDA for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, FDA relayed concerns regarding functional unblinding to Lykos Therapeutics.[20] FDA requested that a Participant Blinding Study be performed for MAPP2 study participants.[21] The MAPP2 Blinding Survey results showed that 94.2% of study participants who received MDMA were positive or believed that they had received MDMA.[22] Correspondingly, 75% of study participants who received placebo were positive or believed they had received placebo. These results from the Blinding Survey confirmed that study participants were functionally unblinded during the study.

The Advisory Committee expressed concerns that unblinding of therapy providers may have impacted the psychotherapy participants received due to the flexibility afforded by the MAPS Manual.[23] Lykos Therapeutics responded to concerns about unblinding of psychotherapy providers by citing the inclusion of blinded independent raters who were responsible for assessing CAPS-5 rating.[24] While the inclusion of an independent rater addressed the blinding of performing the CAPS-5 rating analysis, it did not address functional unblinding of therapy providers and the impact of functional unblinding of therapy providers may have on CAPS-5 ratings scores.

Durability of Effect

The Advisory Committee and FDA noted several study design flaws. Specifically, FDA highlighted that there was no standardization of time in which study participants participated in MPLONG.[25] The lack of standardization in study participant participation resulted in the collection CAPS-5 ratings of study participants at either 6–12 months, 13–18 months, 19–24 months, or > 24 months but not at each time interval. Thus, the results of the MPLONG show a fragmented viewpoint as opposed to a longitudinal viewpoint of durability.

The Advisory Committee questioned the durability of the results obtained by the clinical studies due to the lack of diversity in the participants of the studies.[26] The Advisory Committee noted that 84.8% of MAPP1 participants identified as White and that there was a complete absence of study participants who identified as Black or African American.[27] The lack of diversity in study participants persisted in the MAPP2 study where 69.8% participants identified themselves as White. The Advisory Committee expressed concern that the lack of diversity in study participants may inaccurately reflect the prevalence of disease across races and ethnicities. The Advisory Committee further expressed that the effectiveness identified in the clinical studies may not translate to all patient populations due to the lack of diversity.[28]

In addition to these factors, FDA and the Advisory Committee expressed concerns about the effectiveness of the study results due to uncontrolled and interim use of psychotropic substances, such as MDMA, ketamine, or 5-methoxy-DMT. Collectively, 42% of study participants who participated in MPLONG (23% from treatment group and 19% from the placebo control group) sought MDMA, ketamine, or 5-methoxy-DMT outside the clinical trial after their completion of the study.[29]

Safety and Risk of Abuse

The absence of clinical laboratory data collected by Lykos Therapeutics raised concerns for several Advisory Committee members.[30] The Advisory Committee specifically noted that the NDA submitted by Lykos contained hepatotoxicity as an adverse event but failed to report liver function laboratory assessments.[31] In addition to the lack of clinical laboratory results, the Advisory Committee and FDA expressed concern for what they perceived to be inadequate characterization of the cardiovascular effects. FDA has indicated that without sufficient data characterization of adverse event, such as hepatotoxicity and cardiovascular risks, they cannot appropriately describe risks associated with a drug or therapy on a drug label.[32]

Despite the guidance provided by FDA, Lykos Therapeutics did not systematically collect neutral, positive, or favorable adverse effects in response to MDMA treatment.[33] Instead, Lykos Therapeutics collected only negative adverse effects characterized as undesirable, unfavorable, inappropriate, and abnormal.[34] The absence of data related to positive adverse effects presents a challenge to FDA’s assessment and characterization of abuse potential for MDMA. Without an understanding of both the positive and negative adverse effects, FDA is not able to comprehensively and sufficiently prepare a drug label that will help inform providers monitoring patients. A provider’s ability to recognize both positive and negative adverse events is particularly important for psychedelics as medications because providers will need to clinically assess when a patient may safely be discharged from a medication session.

Safety and Risk of Abuse

FDA’s decision represents a significant setback for Lykos Therapeutics and the broader movement to integrate psychedelic therapeutics into mainstream mental health care. Among supporters of psychedelic therapies, there are those who fear FDA’s decision may hinder innovation and progress in the field. However, experts believe that progress can and will be made to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of MDMA therapeutic use.

For others, FDA’s decision signifies that FDA is cautious in establishing the bar for approval of the first psychedelic therapy. The rigor of the approval process may help legitimize psychedelics and reduce the stigma associated with them. It is believed that the decision will encourage companies involved in the development of psychedelic therapies to work even more closely with FDA throughout the approval process, providing detailed data and adhering to regulatory guidelines. These efforts will build trust and further ensure that MDMA and other psychedelics are viewed as legitimate medical treatment options, rather than merely as recreational substances.

[1] Myron Stolaroff (1997). The Secret Chief Revealed: Conversations with Leo Zeff, Pioneer in the Underground Psychedelic Therapy Movement. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelics Studies (MAPS).

[2] George Greer & Requa Tolbert, Subjective Reports of the Effects of MDMA in a Clinical Setting. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 18(4), 319–327 (1986), https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1986.10472364.

[3] Lykos Therapeutics. Lykos Therapeutics Announces Complete Response Letter for Midomafetamine Capsules for PTSD, https://news.lykospbc.com/2024-08-09-Lykos-Therapeutics-Announces-Complete-Response-Letter-for-Midomafetamine-Capsules-for-PTSD, (content current as of August 9, 2024).

[4] United States Food and Drug Administration. UPDATED MEETING TIME AND PUBLIC PARTICIPATION INFORMATION: June 4, 2024: Meeting of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement, https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/updated-meeting-time-and-public-participation-information-june-4-2024-meeting-psychopharmacologic, (content current as of June 4, 2024) [hereinafter FDA, UPDATED MEETING].

[5] David Millis, Olivia Morgan & Victoria Sammarco (2024) Midomafetamine Cpasules (NDA215455) Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee. [PowerPoint Presentation] https://www.fda.gov/media/179061/download.

[6] United States Food and Drug Administration. Assessment of Abuse Potential of Drugs, https://www.fda.gov/media/116739/download. (content current as of August 9, 2024).

[7] FDA, UPDATED MEETING, supra note 4.

[8] United States Food and Drug Administration. June 4, 2024 Meeting of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/live/JqQKP8gcY1E [hereinafter FDA, Meeting of the PDAC].

[9] Jennifer M. Mitchell, Michael Bogenschutz, Alia Lilienstein, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Nat Med 27, 1025–1033 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3; Jennifer M. Mitchell, Marcela Ot’alora G., Bessel van der Kolk, et al. MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med 29, 2473–2480 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02565-4.

[10] Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Manual for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. https://maps.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/MDMA-Assisted-Psychotherapy-Treatment-Manual-V8.1-22AUG2017.pdf. (content current as of October 1, 2024).

[11] Mitchell et al., MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, supra note 9; Mitchell et al., MDMA-assisted therapy for moderate to severe PTSD: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial, supra note 9.

[12] Berra Yazar-Klosinski (2024) Efficacy. [PowerPoint Presentation] https://www.fda.gov/media/179062/download.

[13] FDA, UPDATED MEETING, supra note 4.

[14] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5.

[15] Id.

[16] FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Bethany Lindsay, Footage of Therapists Spooning and Pinning Down Patient in B.C. Trial for MDMA Therapy Prompts Review. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-mdma-therapy-videos-1.6400256. (content current as of April 9, 2022).

[20] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5; FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[21] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5; FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[22] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5.

[23] FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[24] Id.

[25] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5; FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[26] Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[27] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5; FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[28] Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[29] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5.

[30] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5; FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[31] FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[32] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5; FDA, Meeting of the PDAC, supra note 8.

[33] Millis, Morgan & Sammarco, supra note 5.

[34] Id.

Update Magazine

Winter 2025