“Modernized” Food Manufacturing Enforcement: Trends in FDA Warning Letters

By Joshua Oyster & Chadli Pittman

I. Introduction

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), as amended by the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA),[1] empowers the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to regulate the safety and quality of the nation’s food supply. For example, FDA considers a food adulterated in violation of the FDCA if: i) it consists in whole or in part of any filthy, putrid, or decomposed substance or is otherwise unfit for food[2]; or ii) it has been prepared, packed, or held under insanitary conditions whereby it may have become contaminated with filth, or whereby it may have been rendered injurious to health.[3] Additionally, the FDCA prohibits the operation of a food facility in violation of hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls (PC) requirements.[4] FDA has implemented its statutory authorities through a series of regulations governing current good manufacturing practice (cGMP), hazard analysis, and PC requirements.[5]

In 2015, FDA finalized the current generally applicable regulations for human and animal foods as part of its implementation of FSMA[6] with compliance dates staggered over the next several years.[7] This article does not focus on FDA’s specialized, product-specific regulations governing the processing and production of certain types of food, including seafood,[8] juice,[9] low-acid canned food,[10] produce,[11] and infant formula.[12]

FDA monitors the compliance of food facilities with its standards through a variety of mechanisms, including by conducting inspections. FDA conducts thousands of inspections of both U.S. and foreign food facilities every year. If FDA identifies significant concerns during an inspection, FDA may issue a warning letter citing the relevant violations and urging the affected company to come into immediate compliance. Because FDA issues warning letters far more frequently than it pursues more formal judicial enforcement action (e.g., seizure, consent decree) against food facilities, trends in FDA warning letters can help identify areas of focus in FDA enforcement.

This article analyzes trends in FDA warning letters relating to the food cGMP and PC requirements. As discussed herein, between January 2017 and December 2023, FDA issued 149 warning letters to human food facilities and 37 warning letters to animal food facilities citing violations of the applicable food cGMP and PC requirements. The most cited violations for human food facilities related to the agency’s sanitary operations, preventive controls, and hazard analysis requirements. The most cited violations for animal food facilities related to plant operations, hazard analysis, and sanitation. Food facilities should review their processes and practices in these critical areas to ensure they align with FDA’s expectations.

II. Overview of FDA’s cGMP, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls Regulations for Human and Animal Foods

FDA originally adopted cGMP regulations for the manufacture, processing, packing, and holding of human foods in 1969.[13] These standards were intended to assure that food for human consumption was safe and was prepared, packed, and held under sanitary conditions.[14] In 1986, FDA substantially revised and expanded these cGMP regulations to better ensure the production of safe and sanitary foods.[15] No similar cGMP regulations for animal foods existed.

In 2011, Congress enacted FSMA, which, among other things, required food facilities to comply with hazard analysis and PC requirements and directed FDA to promulgate new regulations. In 2015, FDA issued final rules implementing these new FSMA requirements with respect to both human foods (21 C.F.R. Part 117)[16] and animal foods (21 C.F.R. Part 507).[17] The Preventive Controls for Human Foods (PCHF) Final Rule codified the requirements for applicable food facilities to establish and implement hazard analysis and risk-based PC. Under these regulations, food facilities are generally required to maintain a food safety plan, perform a hazard analysis, institute PC for the mitigation of identified hazards, monitor their PC, conduct verification activities to ensure PC are effective, take appropriate corrective actions, and maintain records documenting these actions.[18] Additionally, the PCHF Final Rule for human foods modernized the cGMP provisions previously contained in Part 110 and re-established them as part of the new Part 117.[19] Among the cGMP-related revisions, FDA made a previously nonbinding education and training provision a binding requirement,[20] and clarified that cGMPs address allergen cross-contact.[21]

FDA’s Preventive Controls for Animal Food (PCAF) Final Rule for the first time established cGMP requirements for animal foods in addition to implementing the hazard analysis and risk-based PC requirements of FSMA for animal foods.[22] The animal food requirements in Part 507 are similar to the human food requirements in Part 117 but take into consideration the unique aspects of the animal food industry and the diversity in types of animal food facilities.[23]

Both the PCHF Final Rule and PCAF Final Rule established staggered compliance dates for the new regulations. In general, human food businesses not considered small or very small were required to comply with Part 117 by September 2016, and animal food businesses not considered small or very small were required to comply with the cGMP aspects of Part 507 by September 2016 and the PC aspects of Part 507 by September 2017. Smaller businesses and those engaged in certain niche activities (e.g., packing or holding produce raw agricultural commodities) were subject to more protracted compliance dates.[24]

Notably, the old Part 110 regulations currently exist in a state of regulatory “purgatory.” FDA’s intent as part of the PCHF Final Rule was to require continued compliance with the existing human food cGMP requirements in Part 110 until the applicable Part 117 compliance dates passed and then to remove Part 110 altogether.[25] In 2018, however, after certain compliance dates related to Part 117 had been extended, FDA announced that it would “remove Part 110 in a separate action after all establishments have reached their compliance for the part 117 cGMPs.”[26] Although these compliance dates have all since passed and FDA is now applying Part 117 cGMPs to all applicable facilities, FDA has not yet formally removed Part 110 from the Code of Federal Regulations.

III. Warning Letter Trends

Most FDA inspections do not lead to the issuance of a warning letter. Based on public FDA inspection data since FY 2017, PC inspections of human food facilities in the United States have been classified as “official action indicated” or “OAI” (meaning objectionable conditions were found and regulatory action is recommended) only 1% of the time.[27] Inspections of animal food facilities have been classified as OAI 3.1% of the time.[28] FDA issues warning letters to some, but not all, facilities that have had inspections classified as OAI. Nonetheless, when they are issued, warning letters are instructive for illustrating FDA’s enforcement priorities and areas of focus.

To assess the most frequently cited human and animal food manufacturing violations and identify trends, we analyzed published FDA warning letters to identify letters citing Part 110, Part 117, or Part 507 violations between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023.[29] First, we identified all warning letters that were issued to human food facilities citing a violation of Part 110 or Part 117 and to animal food facilities citing a violation of Part 507. Then, we grouped the specific violations within each warning letter by section of the regulation (e.g., § 117.35 for sanitary operations). We analyzed the most frequently cited violations to identify trends over time.

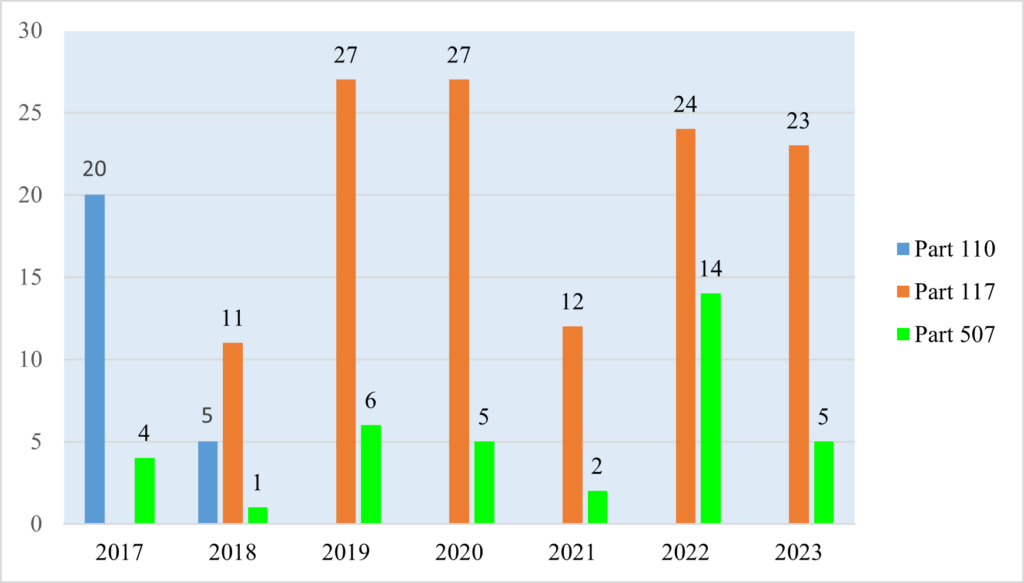

Figure 1: Total Number of cGMP and PC Warning Letters Issued to Human/Animal Food Facilities (2017–2023)

As illustrated in Figure 1, between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023, FDA issued 149 cGMP- and PC-related warning letters to human food facilities, and 37 to animal food facilities. FDA warning letters generally stopped citing Part 110 once the Part 117 compliance date for a human food establishment had passed. FDA’s first warning letter citing a violation of Part 117 was issued on March 16, 2018, and the last warning letter citing a violation of Part 110 was on August 15, 2018.

The number of warning letters issued to human food facilities dipped during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021ut has otherwise remained relatively consistent over time.[30] On the other hand, the number of warning letters issued to animal food facilities has varied significantly from year to year with no obvious explanation for stark changes, such as the significant increase in warning letters in 2022 (14 letters) followed by a reversion to the mean in 2023 (five letters).

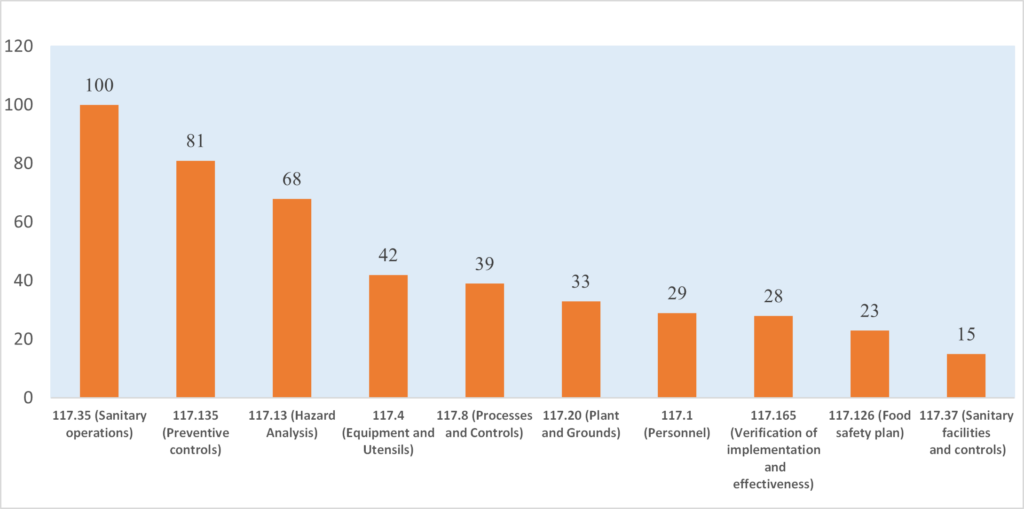

Figure 2: Top 10 Most-Cited Violations of Part 117 in FDA Warning Letters

Figure 2 illustrates the top 10 most-cited violations of Part 117 in FDA warning letters issued between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023. FDA cited 100 violations of the sanitary operations requirements in § 117.35, the most-cited provision of part 117. The sanitary operations regulation, which was adapted from the original Part 110 cGMP regulations, addresses, among other things, pest control and general maintenance requirements. Common pest control issues cited in warning letters included observations of rodent gnaw holes in bags of raw ingredients,[31] rodent pellets around a facility’s grounds,[32] and waste and unused equipment accumulating in areas near production and packing areas.[33] General maintenance violations cited in warning letters included gaps observed between the roof and walls of a production facility,[34] ripped and damaged curtains within a facility,[35] and missing panels in the storage and cooling areas of a facility,[36] which FDA noted may allow for birds and other creatures to contaminate the end-product.

FDA cited 81 violations of the second most-cited Part 117 provision, the preventive controls requirement in § 117.135. The preventive controls requirement not only mandates that preventive controls be identified and implemented to assure that hazards requiring a preventive control are significantly minimized or prevented, but also requires the implementation of applicable process controls, food allergen controls, and sanitation controls. Common preventive control issues cited in FDA warning letters included food production areas testing positive for the presence of environmental pathogens like Salmonella[37] and Listeria monocytogenes[38] due to the lack of adequate controls to prevent such contamination, and noncompliance with the allergen and sanitation controls in a facility’s food safety plan.[39]

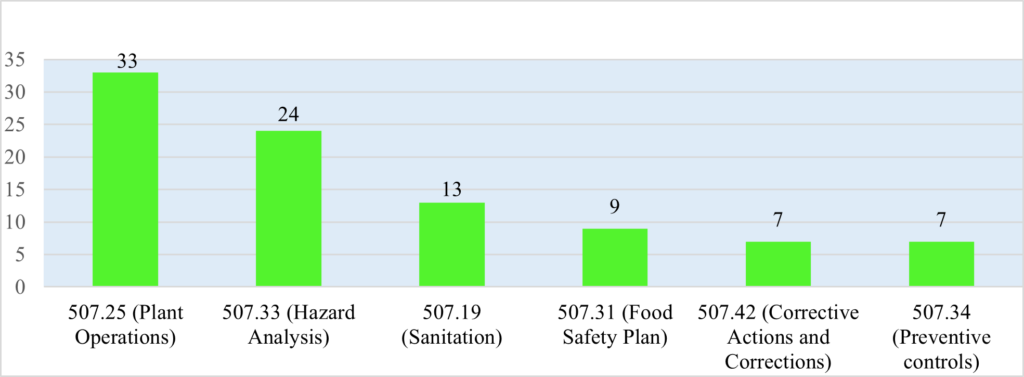

Figure 3: Top Six Most-Cited Violations of Part 507 in FDA Warning Letters

Figure 3 illustrates the top six most-cited violations of Part 507 in FDA warning letters issued between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023. FDA cited 33 violations of the plant operations requirements in § 507.25. Among these plant operations requirements, FDA warning letters most frequently cited violations of the management responsibilities described in § 507.25(a). For example, one warning letter cited § 507.25(a) when a facility’s employees performed sanitation procedures haphazardly, which resulted in over-spray from the sanitation falling into open tubs of exposed meat held for use as pet food.[40] Other warning letters cited § 507.25(b) concerning the management of raw materials, when, for instance, a facility used tissue from animals that died from a cause other than slaughter in the manufacturing of its pet food, without first determining whether the animals suffered any type of illness or injury, or whether the animal was administered any potentially hazardous medication.[41]

FDA warning letters cited animal food facilities for violating the hazard analysis requirement of § 507.33 when, for example, a facility failed to identify and evaluate hazards specific to the source of their raw production material, in violation of § 507.33(a),[42] and when a facility failed to sufficiently assess the probability and potential severity of a toxicity hazard occurring in the absence of a preventive control as required by § 507.33(c).[43]

IV. Best Practice Recommendations

FDA enforcement of food cGMP and PC requirements plays a critical role in ensuring the safety of the nation’s food supply. As evidenced by warning letter data over the past seven years, FDA commonly focuses on sanitation, pest control, general maintenance, and other traditional cGMP issues that have historically been a priority of food enforcement. Yet warning letters also now frequently cite hazard analysis and other requirements that were only introduced as part of the more modern requirements adopted under FSMA. Food facilities should take the following actions now to ensure the success of their next FDA inspection and reduce the risk of government scrutiny:

- Facilities should ensure their pest control systems and processes conform to industry best practices. Pest control concerns were one of the most frequently cited issues in warning letters to both human and animal food facilities. Although the need for adequate pest control is undoubtedly recognized as a baseline requirement across the industry, the fact that FDA warning letters continue to cite pest control problems with such frequency suggests that there remains opportunity for improvement and that FDA will continue to focus on this issue. Accordingly, manufacturers should critically assess their pest control processes and strategies (e.g., frequency and extent of trash removal, cleaning of break rooms, maintenance checks of exterior walls and doors) and ensure they implement enhancements proactively before a problem develops and before an inspector comes on-site. Significant pest contamination issues can lead to disruptions to production operations as well as have the potential to trigger costly recalls of product already in the marketplace.

- Facilities should consistently assess and enhance their training programs. FDA regulations require all owners, operators, or agents in charge of a facility to ensure that all individuals who manufacture, process, pack, or hold food be qualified to perform their assigned duties.[44] Issues observed during FDA inspections and cited in FDA warning letters are commonly caused, at least in part, by training issues. Perhaps an employee was trained on a sanitation process when they were first hired, but then there was no refresher training. Perhaps a training process on how to sanitize a production line was adequate when it was first implemented but then it was never updated after the equipment on the production line changed. Ensuring the adequacy of training to support a facility’s current operations and personnel is paramount. Facilities should regularly be evaluating their training programs (scope, frequency, format, etc.) in light of available performance and quality metrics to identify opportunities for improvement.

- Facilities should leverage the resources provided by FDA to both structure and monitor their food safety plan. In conjunction with the PCHF and PCAF rules, FDA has also created a slew of resources to assist facilities with compliance. One potentially helpful tool for entities wondering where to start is FDA’s Food Safety Plan Builder Tool.[45] This tool is designed as a user-friendly resource to assist owners and operators of a food establishment with the development of a food safety plan that is specific to their facilities, thus providing a potentially simplified pathway to compliance. Facilities should continuously engage with these kinds of compliance resources, both when considering making changes to their current food safety plans and when performing oversight to ensure that operations remain FDA-compliant.

In addition to ensuring regulatory compliance, implementing these recommendations will help food facilities mitigate the risk of production disruptions, product recalls, and reputational damage that often accompanies FDA enforcement. Food facilities and entities investing in the food industry should continue to monitor regulatory and enforcement developments related to manufacturing and safety to keep abreast of FDA’s evolving priorities.

[1] Pub. L. No. 111-353, 124 Stat. 3885 (2011).

[2] 21 U.S.C. § 342(a)(3).

[3] 21 U.S.C. § 342(a)(4).

[4] See 21 U.S.C. §§ 350g, 331(uu).

[5] See 21 C.F.R. Parts 110 (historical cGMP requirements for human food), 117 (current requirements for human food), and 507 (current requirements for animal food).

[6] See Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food, 80 Fed. Reg. 55908 (Sept. 17, 2015); Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Food for Animals, 80 Fed. Reg. 56170 (Sept. 17, 2015).

[7] Compliance dates for Parts 117 and 507 were staggered based on the size and type of business. See, e.g., FSMA Compliance Dates, U.S. Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-compliance-dates#HumanFood (last updated May 6, 2019).

[8] 21 C.F.R. Part 123.

[9] 21 C.F.R. Part 120.

[10] 21 C.F.R. Part 113.

[11] 21 C.F.R. Part 112.

[12] 21 C.F.R. Part 106.

[13] 34 Fed. Reg. 6977 (Apr. 26, 1969) (adopting human food cGMP regulations in what was then 21 C.F.R. Part 128).

[14] Id. at 6978.

[15] 51 Fed. Reg. 22458 (June 19, 1986) (revising human food cGMP regulations in 21 C.F.R. Part 110).

[16] 80 Fed. Reg. 55908 (Sept. 17, 2015) [hereinafter PCHF Final Rule].

[17] 80 Fed. Reg. 56170 (Sept. 17, 2015) [hereinafter PCAF Final Rule].

[18] See 21 C.F.R. Part 117, Subpart C; see 80 Fed. Reg. at 55911.

[19] See 21 C.F.R. Part 117, Subpart B; see 80 Fed. Reg. at 55911, 55913.

[20] See 21 C.F.R. § 117.4(b).

[21] See 21 C.F.R. § 117.10(b).

[22] 80 Fed. Reg. 56170 (Sept. 17, 2015).

[23] See, e.g., 80 Fed. Reg. at 56173.

[24] See 81 Fed. Reg. 57784, 57786 (Aug. 24, 2016); FSMA Compliance Dates, supra note 7.

[25] See 80 Fed. Reg. at 56144 (“Remove and reserve part 110, effective September 17, 2018.”).

[26] 83 Fed. Reg. 46104, 46106 (Sept. 12, 2018).

[27] FDA-TRACK: Preventive Controls and Current Good Manufacturing Practice Measures, U.S. Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-track-agency-wide-program-performance/fda-track-preventive-controls-and-current-good-manufacturing-practice-measures (last visited Feb. 26, 2024).

[28] Id.

[29] See, e.g., Warning Letters, U.S. Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/compliance-actions-and-activities/warning-letters (last visited Feb. 26, 2024).

[30] See, e.g., FDA-TRACK: Preventive Controls and Current Good Manufacturing Practice Measures, supra note 27 (illustrating that FDA performed less than a quarter of the human food facility PC inspections it did during its peak in 2019).

[31] See Warning Letter: Crispy Delight Corp., U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Sept. 6, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/crispy-delight-corp-585315-09062019.

[32] See Warning Letter: STC India Private Limited, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (July 21, 2023), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/stc-india-private-limited-661775-07212023.

[33] See Warning Letter: Florida Gold Foods LLC, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Nov. 22, 2022), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/florida-gold-foods-llc-637153-11222022.

[34] See Warning Letter: Orangeburg Pecan Company Inc, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (May 17, 2018), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/orangeburg-pecan-company-inc-544396-05172018.

[35] See Warning Letter: Bhavani Fruits & Vegetables LLC, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Mar. 16, 2018), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/bhavani-fruits-vegetables-llc-541761-03162018.

[36] See Warning Letter: New England Confectionery Company, Inc., U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (May 16, 2018), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/new-england-confectionery-company-inc-545899-05162018.

[37] See Warning Letter: Kerry Inc, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (July 26, 2018), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/kerry-inc-560168-07262018.

[38] See Warning Letter: Friendly’s Manufacturing and Retail LLC, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Nov. 22, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/friendlys-manufacturing-and-retail-llc-590821-11222019.

[39] See Warning Letter: Chukar Cherry Company Inc., U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (July 27, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/chukar-cherry-company-inc-573446-06272019.

[40] See Warning Letter: Lea-Way Farms Inc. dba Blue Ridge Beef, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (June 26, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/lea-way-farms-inc-dba-blue-ridge-beef-597944-06262020.

[41] See id.

[42] See Warning Letter: Valley Proteins, Inc., U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Nov. 18, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/valley-proteins-inc-582508-11182019.

[43] See Warning Letter: DSM Nutritional Products, LLC, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Oct. 11, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/dsm-nutritional-products-llc-578300-10112019.

[44] See 21 C.F.R. §§ 117.4, 507.4.

[45] See Food Safety Plan Builder, U.S. Food & Drug Admin., https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/food-safety-plan-builder (last updated Apr. 8, 2020).

Update Magazine

Spring 2024

JOSHUA OYSTER is a partner in the life sciences regulatory and compliance practice at Ropes & Gray LLP in Washington, DC where he steers clients through a wide range of FDA regulatory issues to help them bring innovative products to market while also ensuring regulatory compliance. Josh helps companies navigate FDA inspections, warning letters, product recalls, and other compliance and enforcement matters.

JOSHUA OYSTER is a partner in the life sciences regulatory and compliance practice at Ropes & Gray LLP in Washington, DC where he steers clients through a wide range of FDA regulatory issues to help them bring innovative products to market while also ensuring regulatory compliance. Josh helps companies navigate FDA inspections, warning letters, product recalls, and other compliance and enforcement matters. CHADLI PITTMAN is an associate in the life sciences regulatory and compliance practice at Ropes & Gray LLP in Washington, DC.

CHADLI PITTMAN is an associate in the life sciences regulatory and compliance practice at Ropes & Gray LLP in Washington, DC.