Drug CGMP During COVID-19: An Analysis of Recent FDA Warning Letters

By Joshua Oyster, Rebecca H. Williams & Helen K. Ryan

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) ability to monitor drug product quality and manufacturing compliance through in-person facility inspections and forced the agency to rely on alternative tools that may reshape the agency’s approach to manufacturing oversight for years to come. Following the agency’s initial pause on most domestic and foreign facility inspections in March 2020, FDA has had difficulty returning to its pre-pandemic inspection cadence and volume, creating a significant backlog in both foreign and domestic surveillance inspections.

Despite the significant decrease in the number of FDA inspections, FDA enforcement actions have nonetheless continued during the pandemic. Over the past two years, FDA has issued a substantial number of warning letters to drug and biologic product manufacturers for violations of current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) requirements and related quality issues, though the total number is less when compared to pre-pandemic years. These notably include first-of-their-kind CGMP letters based solely on FDA’s authorities under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) to request records and test product samples, which highlights the agency’s increased reliance on alternative inspection tools. This article reviews the impact of COVID-19 on FDA’s ability to monitor and enforce CGMP compliance and analyzes the resulting shift in manufacturing-related warning letters based on FDA’s alternative tools and other recent trends.

I. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on FDA Inspections

As COVID-19 began to take hold in the United States in March 2020, FDA temporarily postponed all domestic and foreign routine surveillance facility inspections but continued inspections deemed to be “mission critical” where possible.[1] The initial postponement extended until late July 2020, when FDA resumed prioritized domestic inspections, including pre-approval, surveillance, and for-cause inspections based on FDA’s COVID-19 Advisory Rating System.[2] Foreign inspections that were not deemed mission critical remained on hold until October 2020, when the agency started to resume limited pre-approval inspections,[3] and January 2021, when the agency started to resume foreign surveillance inspections.[4]

The consequences of the halt in inspections have been significant. From March 2020 through March 2021, FDA conducted only 155 drug inspections and sixty-three biologics inspections,[5] compared to the more than 1,650 drug inspections conducted in each of fiscal years 2018 and 2019.[6] The reduction in inspections did not go unnoticed: in January 2021, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report highlighting concerns raised by the lack of FDA inspections,[7] which led to a congressional hearing in March[8] and a congressional request for information in July.[9] Although the agency made a concerted effort to reduce the inspection backlog following the initial GAO report,[10] continued surges in COVID-19 infections have hindered these efforts. For example, FDA was forced to temporarily pause all non-mission-critical domestic surveillance inspections from December 29, 2021, until February 7, 2022, due to surges caused by the omicron variant, and FDA does not expect to resume a regular cadence of foreign surveillance inspections until April 2022.[11]

To maintain some degree of oversight over drug manufacturing quality compliance during the inspections halt, FDA has leveraged the power of “alternative tools,” including records requests, product sampling, and what the agency has termed “remote interactive evaluations.” The rest of this section discusses each of these methods in turn.

Throughout the pandemic, FDA has relied on records requests when on-site inspections were not practicable to help assess drug manufacturers’ continued compliance with CGMP. FDA’s records request authority under Section 704(a)(4) of the FDCA provides that “any records or other information that the Secretary may inspect . . . from a person that owns or operates an establishment that is engaged in the manufacture, preparation, propagation, compounding, or processing of a drug shall, upon the request of the Secretary, be provided . . . in advance of or in lieu of an inspection.”[12] The refusal to permit access to or copying of any records required by 704(a)(4) constitutes a prohibited act under the FDCA.[13] Additionally, a facility’s failure to produce requested records in a timely manner or refusal to provide records that are not unreasonably redacted is considered a “delay” or “limiting” of an inspection.[14] Any drug that is manufactured, processed, packed or held in an establishment that delays, denies, limits, or refuses an inspection is deemed to be adulterated.[15]

In addition to records requests, FDA has also increasingly relied on analytical testing of product samples to assess product quality, particularly for drugs produced by foreign manufacturers. FDA is authorized by the FDCA to collect samples of drugs for examination or analysis.[16] While samples may be collected during facility inspections, samples are also frequently collected while goods are waiting to be cleared through customs for entry into the U.S.[17] If, based on sample testing or otherwise, the product appears to be adulterated, misbranded, or otherwise in violation of the FDCA, the product will be refused entry into the U.S.[18]

FDA has also employed “remote interactive evaluations” of drug and biologic manufacturing facilities to increase agency oversight.[19] Although the FDCA does not explicitly grant FDA the authority to conduct remote interactive evaluations, FDA published guidance in April 2021 describing the process by which the agency can request and conduct voluntary remote interactive evaluations for pre-approval, postapproval, surveillance, follow-up, and compliance inspections based on agency needs and travel limitations during the COVID-19 public health emergency.[20] The request for a remote interactive evaluation may include livestream or prerecorded video to examine facilities, operations, data, and other information and will generally be accompanied by a 704(a)(4) records request.[21] FDA will “usually present” a list of observations at the completion of a remote interactive evaluation; however, this list is not considered final agency action nor is it the same as a Form FDA 483 issued following an on-site inspection.[22]

Although FDA’s authorities to request records and conduct sample testing are by no means new, FDA’s substantial reliance on these authorities to support warning letters, as discussed below, is a result of the agency’s inability to rely on in-person inspections to monitor CGMP compliance and product quality during the pandemic.

II. Analysis of Manufacturing-Related Warning Letters During COVID-19

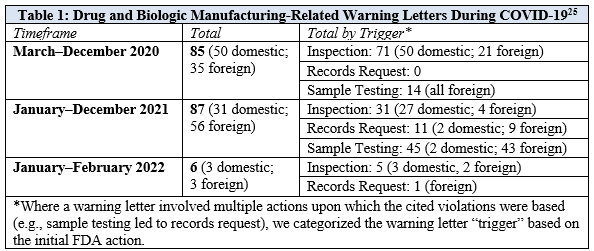

To assess the impact of FDA inspection limitations and the agency’s use of alternative tools to facilitate CGMP-related enforcement, we analyzed FDA warning letters issued to drug and biologics manufacturers from March 1, 2020, through February 28, 2022.[23] We focused on letters that cited CGMP and other product manufacturing or quality issues, as well as letters that cited refusals to comply with FDA records requests. We categorized these letters by the type of FDA action that triggered the letter, such as a facility inspection, records request, or sample testing. To date, FDA has not issued any warning letters based on voluntary remote interactive evaluations. An overview of the total letters, as well as the basis for issuing the letters, is provided in Table 1.[24]

The total number of manufacturing-related warning letters has been similar during each of the first two years of the pandemic: there were eighty-five letters during the first ten months of the pandemic—from March through December 2020—and another eighty-seven letters during all of 2021. While more than 80% of the manufacturing-related warning letters issued in 2020 were triggered by on-site inspections, only 35% of the warning letters in 2021 were triggered by on-site inspections. This decrease in inspection-based warning letters in 2021 corresponded with a significant increase in warning letters based on sample testing and records requests, which accounted for 52% and 13% of total letters, respectively.

Consistent in both 2020 and 2021, inspection-based warning letters were largely focused on domestic manufacturers, while sample testing-based warning letters were almost exclusively issued to foreign manufacturers. In 2021, foreign manufacturers received the majority of CGMP-related warning letters, which reflects FDA’s increased use of sample testing and records requests to support enforcement against foreign facilities. While only a handful of warning letters have been issued so far in 2022, these letters suggest there may be a renewed emphasis on inspections-based warning letters in the coming year.

To understand the impact of alternative tools on warning letter citations, we categorized the warning letters by their trigger and analyzed specific trends for warning letters based on inspections, records requests, and sample testing, respectively.

A. Inspections

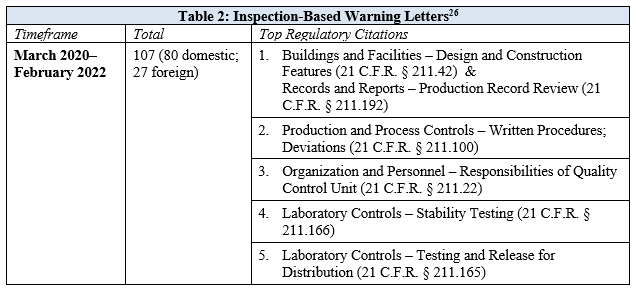

From March 2020 through December 2020, FDA issued seventy-one manufacturing-related warning letters based on facility inspections, all of which were conducted prior to the March 2020 inspections pause. The number of warning letters triggered by inspections substantially decreased in 2021, which is not surprising given the significant decrease in the number of in-person inspections performed by FDA during the beginning of the pandemic. Nonetheless, 77% of the thirty-one inspection-based warning letters issued in 2021, and the five inspections-based warning letters issued in 2022, were based on inspections conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic after FDA’s initial inspections pause. An overview of the most frequent regulatory citations highlighted in inspection-based warning letters is provided in Table 2.

The top citations, 21 C.F.R. § 211.42 (facility design and construction features) and 21 C.F.R. § 211.192 (production record review), were cited with equal frequency across warning letters. While the citations to 21 C.F.R. § 211.192 consistently highlighted deficiencies regarding investigations of batches that failed to meet specifications, the citations to 21 C.F.R. § 211.42 were more varied and highlighted deficiencies related to systems for monitoring environmental conditions in aseptic processing areas, systems for cleaning and disinfecting rooms and equipment to control aseptic conditions, and control systems to prevent contamination or mix-ups, among other things. Two citations that were common across both 2020 and 2021, but cited with increased frequency in 2021, included 21 C.F.R. § 211.100, which addressed deficiencies in qualifying and validating the equipment and processes for manufacturing drug product, and 21 C.F.R. § 211.22, regarding the failure of the quality control unit to exercise its responsibility to ensure drug products manufactured are in compliance with CGMP and meet established specifications for identity, strength, quality, and purity. The increased frequency of citations related to deficiencies in the quality control unit in 2021 reflects FDA’s continued emphasis on the importance of internal company structures that ensure product quality.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, FDA has also continued its scrutiny of drug compounding and data integrity issues, both of which are longstanding enforcement priorities. While the majority of inspection-based warning letters were issued to drug manufacturers, a significant number of letters since March 2020 were issued to drug compounders, including thirty warning letters to 503A compounding pharmacies and four warning letters to 503B outsourcing facilities relating to CGMP violations.[27] The share of inspection-based warning letters issued to drug compounders highlights FDA’s ongoing focus in this area as part of the agency’s broader efforts to assure the quality of compounded drugs.

With respect to data integrity, approximately 17% of inspection-based warning letters since March 2020 specifically cited the manufacturer for failing to ensure “the accuracy and integrity of data” to support the safety, effectiveness, and quality of manufactured drugs and required the manufacturer to perform data integrity remediation. Because identification of data integrity issues often requires a detailed review and analysis of records—including metadata and audit trails for electronic records and systems—that can only be performed on-site at a facility, these issues are less likely to be identified through records requests or remote evaluations. We expect that FDA will continue to devote attention to data integrity issues as FDA is able to resume its usual volume of in-person inspections.

B. Records Requests

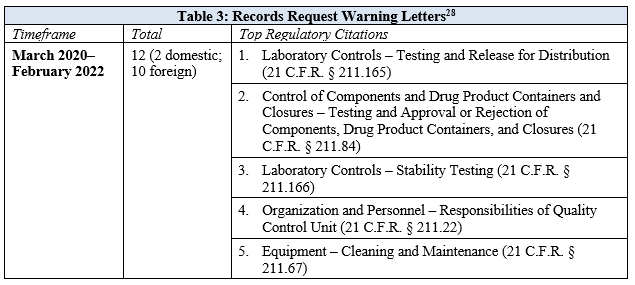

FDA began issuing 704(a)(4) records requests at the outset of the pandemic and issued its first-ever warning letters related to these requests in 2021. The majority of the warning letters arising out of records requests were issued to foreign manufacturers and cited CGMP issues. The only two records request warning letters that were issued to domestic manufacturers did not cite specific CGMP violations, but rather cited each facility’s failure to respond to the request. Records request warning letters were primarily issued to manufacturers of over-the-counter products. An overview of the records request warning letters is provided in Table 3.

Like many of the inspection-based warning letters, those grounded in records requests frequently cited 21 C.F.R. § 211.165, relating to the failure to conduct adequate finished product testing, and 21 C.F.R. § 211.166, relating to the failure to conduct adequate stability studies that demonstrate the drug product remains acceptable throughout the labeled expiry period. Additionally, several warning letters identified deficiencies related to the quality unit under 21 C.F.R. § 211.22. While these citations were generally consistent with inspection-based warning letters, there was an increased citation in records request letters to 21 C.F.R. § 211.84, regarding the failure to adequately test incoming raw materials to determine their identity. Unsurprisingly, the top citation in inspection-based warning letters for building design and construction features was not a frequent citation in records request warning letters given the agency’s limited ability to assess such issues through document review.

Two 2021 warning letters also cite specific issues where compliance with records requests led to an on-site inspection.[29] Specifically, FDA’s warning letter to BBC Group Limited (China) indicates that the facility submitted inconsistent records to FDA in response to a 704(a)(4) records request, which caused the facility to be placed on import alert and triggered an FDA on-site inspection that identified a number of CGMP violations.[30] Further, FDA’s warning letter to Global Sanitizers LLC (U.S.) states that FDA initiated an on-site inspection after the facility failed to respond to two FDA records requests.[31] These letters demonstrate the agency’s willingness to prioritize on-site inspections based on an inadequate response, or lack of a response altogether, to 704(a)(4) records requests.

C. Sample Testing

In both 2020 and 2021, FDA devoted significant resources to sample testing imported goods, with a particular emphasis on hand sanitizer products, which the agency regulates as over-the-counter drugs. While FDA has historically relied on import alerts and product seizures to restrict violative products, during the pandemic the agency also began issuing warning letters and publishing a public list of hand sanitizers that consumers should not use.[32] The agency issued a total of fifty-nine warning letters based on sample testing; fifty-seven letters were issued to foreign manufacturers of hand sanitizer products, one letter was issued to a domestic importer and repacker of hand sanitizer products, and one letter was issued to a domestic manufacturer of other drug products.

All of the sample testing warning letters cite the statutory CGMP provision, 21 U.S.C. § 351(a)(2)(B), as well as other FDCA provisions related to adulterated drugs. Nearly 70% of the sample testing warning letters cited the substitution of a product’s active ingredient(s) for an undeclared or dangerous ingredient, which rendered the products adulterated under 21 U.S.C. § 351(d)(2). Almost one-third of the sample testing warning letters also included a citation to 21 U.S.C. § 351(c), based on the finding that the active ingredient was present at levels lower than what was declared in the labeling, rendering the product adulterated. In the warning letters, FDA leverages these findings to determine that “These products are . . . adulterated within the meaning of section 501(a)(2)(B) (21 U.S.C. 351(a)(2)(B)), in that the [substitution and/or subpotency] demonstrate that the quality assurance within your facility is not functioning in accordance with [CGMP] requirements.”

While FDA frequently conducts sample testing on imported products, CGMP warning letters based solely on such testing (and in the absence of a subsequent inspection) are the first of their kind and reflect the agency’s focus on finding alternative ways to maintain oversight of these manufacturers’ activities and to encourage the removal of violative products from the U.S. market. For example, following sample testing, FDA frequently issued an informal records request (rather than a formal 704(a)(4) request) to the affected facility and requested participation in a teleconference with the agency. Additionally, FDA often requested manufacturers initiate a recall for any products currently in distribution. Given the influx in new manufacturers of hand sanitizer products during the pandemic, it is possible that the agency issued these letters, in part, as a reminder to other manufacturers of the regulatory requirements they must meet.

FDA’s issuance of warning letters based on sample testing may continue, particularly if issues arise with other categories of products that—like hand sanitizers—do not require FDA approval and that may be produced by a substantial number of foreign manufacturers. However, FDA’s ability to take enforcement action based on sample testing is severely limited by the practical realities of conducting such testing. For example, FDA does not have the capacity to sample even a small fraction of the products offered for import or to sample all products currently in interstate commerce. Although sample testing serves as an important deterrent, capacity limitations restrict the utility of sample testing as a stand-alone enforcement tool for ensuring product quality and CGMP compliance.

III. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic upended FDA’s work in myriad ways, causing severe disruption to the agency’s ability to conduct its usual slate of in-person facility inspections to help ensure the quality of the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain. As a result, FDA has relied on alternative mechanisms, such as sample testing, records requests, and remote interactive evaluations to provide oversight. In particular, use of sample testing and records requests has allowed FDA to identify violations of CGMP compliance or product quality issues—even in the absence of an on-site inspection—and issue a substantial number of warning letters focused on manufacturing violations. While the sample testing warning letters tended to cite only general noncompliance with CGMP requirements via citation to the statutory CGMP provision, the records request warning letters included detailed citations to CGMP regulations and bore a closer resemblance to the inspection-based warning letters.

There is some overlap between inspection-based and records request warning letters issues, with frequent citations in both concerning the conduct of stability and finished product testing, as well as quality unit controls. There are, however, some key distinctions. For example, inspection-based warning letters frequently identify deficiencies relating to building design and construction, as well as investigations of batches that fail to meet specifications. The lack of these citations in records request warning letters is likely attributable to the limitations of a paper-based record review.

The agency’s use of sample testing and records requests has been integral to FDA’s efforts to ensure continued CGMP compliance and product quality during a time when the agency’s ability to conduct inspections has been limited. Although FDA has indicated it will continue to leverage these tools after the pandemic has subsided, they will likely supplement, rather than supplant, in-person inspections which continue to be the gold standard for assessing manufacturing quality and compliance.

[1] In determining whether an inspection concerns a “mission critical” issue, FDA considers both the agency’s resources and capabilities for, and the public health risks or benefits posed by, the inspection. See U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Guidance for Industry: Manufacturing, Supply Chain, and Drug and Biological Product Inspections During COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Questions and Answers at 4 (May 17, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/media/141312/download. While both for-cause inspections and pre-approval/prelicense inspections could be deemed mission critical, pre-approval and prelicense inspections are generally outside the scope of this article.

[2] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Prepares for Resumption of Domestic Inspections with New Risk Assessment System (July 10, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-prepares-resumption-domestic-inspections-new-risk-assessment-system.

[3] Statement of Mary Denigan-Macauley before the Subcomm. on Agric., Rural Dev., Food & Drug Admin., and Related Agencies, Comm. on Appropriations, H.R., Drug Safety: FDA’s Future Inspection Plans Need to Address Issues Presented by COVID-19 Backlog at 9 (Mar. 4, 2021), https://www.gao.gov/assets/720/712761.pdf.

[4] U.S. Gov’t. Accountability Off., Report to Congressional Committees: COVID-19 Critical Vaccine Distribution, Supply Chain, Program Integrity, and Other Challenges Require Focused Federal Attention at 150 (Jan. 13, 2021), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-265.pdf.

[5] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Resiliency Roadmap for FDA Inspectional Oversight (May 5, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/media/148197/download?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

[6] See supra note 3 at 6.

[7] See supra note 4.

[8] See supra note 3.

[9] H.R. Comm. on Energy and Com., Letter to Janet Woodcock (July 22, 2021), https://energycommerce.house.gov/sites/democrats.energycommerce.house.gov/files/documents/07.22.21-EC-Letter-to-FDA.pdf.

[10] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., An Update to the Resiliency Roadmap for FDA Inspectional Oversight (November 22, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/media/154293/download.

[11] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., FDA Roundup: February 4, 2022 (Feb. 4, 2022), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-roundup-february-4-2022.

[12] 21 U.S.C. § 374(a)(4).

[13] 21 U.S.C. § 331(e).

[14] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Guidance for Industry: Circumstances that Constitute Delaying, Denying, Limiting, or Refusing a Drug Inspection at 5, 8 (Oct. 22, 2014), https://www.fda.gov/media/86328/download.

[15] 21 U.S.C. § 351(j).

[16] 21 U.S.C. § 372(a).

[17] 21 U.S.C. § 381(a). See also U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Investigations Operations Manual 2021: Chapter 4 – Sampling at 4, https://www.fda.gov/media/75243/download.

[18] 21 U.S.C. § 381(a).

[19] Unlike records requests and sample testing, which are explicitly authorized under the FDCA, remote interactive evaluations are an extra-statutory creation intended to supplement other regulatory oversight activities such as an inspection or records request. U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Guidance for Industry: Remote Interactive Evaluations of Drug Manufacturing and Bioresearch Monitoring Facilities During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency at 3 (Apr. 14, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/media/147582/download.

[20] Id. at 5-7.

[21] Id. at 7-8.

[22] Id. at 12.

[23] FDA’s warning letter database may not post warning letters on the date they are issued. For purposes of this article, we analyzed all warning letters posted as of March 2, 2022. FDA’s warning letter database is available at https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/compliance-actions-and-activities/warning-letters.

[24] To request a copy of the warning letter dataset, please contact Rebecca Williams at [email protected].

[25] See supra note 23.

[26] Id.

[27] Outside of the CGMP warning letters, FDA also issued several warning letters to 503A compounding pharmacies and 503B outsourcing facilities related to the compounder’s failure to meet other conditions for compounding described in the FDCA, such as the requirements for 503B outsourcing facilities to report adverse events.

[28] See supra note 23.

[29] Because the cited violations for these warning letters were based on the facility inspection, we categorized these letters as inspection-based warning letters for purposes of our analysis.

[30] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Warning Letter to BBC Group Limited (Aug. 4, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/bbc-group-limited-614659-08042021.

[31] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Warning Letter to Global Sanitizers LLC (Nov. 8, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/global-sanitizers-llc-614124-11082021.

[32] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., FDA Updates On Hand Sanitizers Consumers Should Not Use (Mar. 2, 2022), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-hand-sanitizers-consumers-should-not-use.

JOSHUA OYSTER is a partner at Ropes & Gray LLP where he steers clients through a wide range of FDA regulatory issues to help them bring innovative products to market while also ensuring regulatory compliance. Among the many clients Josh counsels are leading life sciences and health care companies, as well as private equity firms and investment banks focused on investing in these sectors.

JOSHUA OYSTER is a partner at Ropes & Gray LLP where he steers clients through a wide range of FDA regulatory issues to help them bring innovative products to market while also ensuring regulatory compliance. Among the many clients Josh counsels are leading life sciences and health care companies, as well as private equity firms and investment banks focused on investing in these sectors. REBECCA H. WILLIAMS is an associate at Ropes & Gray LLP. She focuses her practice on FDA regulatory matters and advises life sciences and health care clients on a broad range of regulatory and compliance issues under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and related laws.

REBECCA H. WILLIAMS is an associate at Ropes & Gray LLP. She focuses her practice on FDA regulatory matters and advises life sciences and health care clients on a broad range of regulatory and compliance issues under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and related laws. HELEN K. RYAN is an associate in the life sciences regulatory and compliance group at Ropes & Gray LLP.

HELEN K. RYAN is an associate in the life sciences regulatory and compliance group at Ropes & Gray LLP.