Bad News for Device Sponsors: Panel Meetings were Already Going the Way of the Homework Assignment, and COVID Might “Put the Nail in the Coffin”

By Kristin Zielinski Duggan and Sandra Milena McCarthy[1]

The number of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory panel meetings to review new medical devices has been declining in recent years. In 2019, only one panel meeting was convened by FDA for discussion of a new device undergoing the de novo pathway, and no meetings to review a premarket approval (PMA) application were held. Panel meetings are required in certain circumstances; however, they are time-consuming, resource-intensive, and costly for both FDA and the sponsor and require great efforts to recruit, engage, assess conflicts, and confirm outside experts’ participation in these panels. Panels to review new medical device applications are typically scheduled for one full day, and meetings may span multiple days to review multiple applications. As a way to mitigate expenses but preserve the ability of FDA to seek outside expertise in device reviews, FDA has increasingly relied on “panel homework assignments,” which refers to the practice of selected subject matter experts providing written responses to FDA questions and inquiries as a way to garner input from experts in a particular field and solicit opinions on new devices and the information required to support their entry to market. Now, with the spread of COVID-19 affecting FDA’s ability to hold in-person meetings, including advisory panel meetings, FDA may well turn to panel homework assignments in lieu of panel advisory meetings. Alternatively, FDA may shift to virtual panels (e.g., teleconference or videoconference), an option outlined in FDA’s guidance and regulations but rarely used until the declaration of the COVID-19 public health emergency.

This trend may not be to the advantage of medical device manufacturers. Full-day teleconference meetings are not likely to have the same dynamic as in-person meetings, which allow sponsors and the public to look the panel members in the eye and allow the panel members to hold fruitful discussion amongst themselves. Further, the major disadvantage of utilizing homework assignments is a complete lack of transparency or involvement of the sponsor. While panel homework assignments can most benefit companies in select situations when the clinical community is more likely to agree with the company’s position on the issue than FDA’s position, since FDA controls the experts selected and the briefing materials provided, and the sponsor has no opportunity to provide input into the process, it is less likely that the exercise will end up in the company’s favor.

If FDA plans to rely on panel homework assignments more frequently given the decrease in in-person panel meetings in recent years, it is critical that the agency allow the sponsor more participation in and visibility on the process to ensure a fair and scientifically-valid result.

A Recent Decline in Advisory Panel Meetings

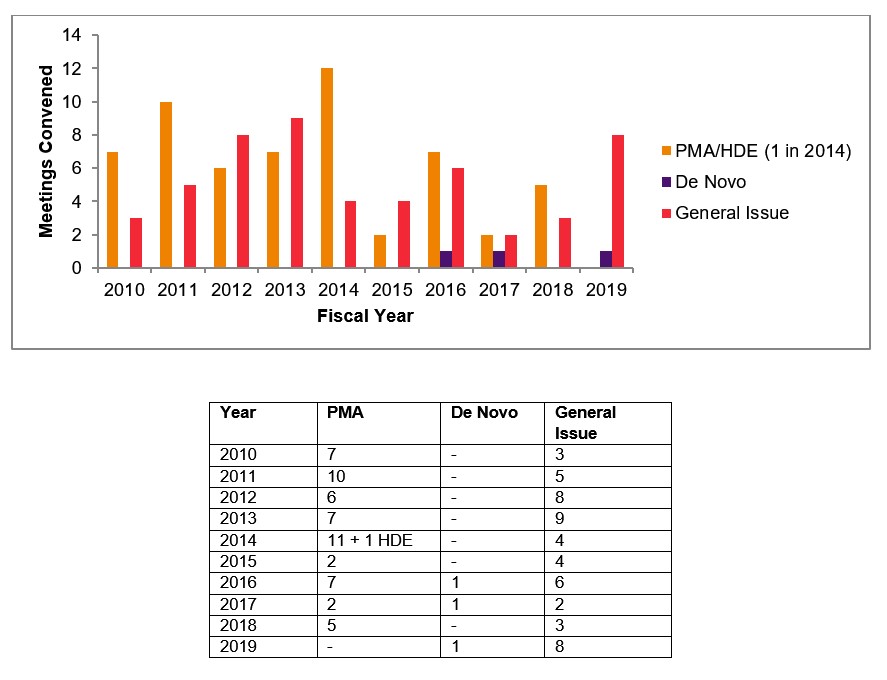

As can be seen in the table and graph below, FDA advisory panel meetings to review new medical devices have been less frequent in the past several years. With the exception of 2017, the number of PMA and de novo device panel meetings has ranged from one to five per year in the last five years. In 2019, the agency convened no PMA meetings and only one meeting to review a de novo request.

In addition to the extensive recruiting, scheduling, and conflicts process FDA must engage in to confirm outside experts’ participation in these panels, both FDA and the sponsor must prepare a large briefing package summarizing the file to be sent to the panelists in advance of the meeting, as well as an approximately hour-long presentation and backup slides to be able to respond to panel questions. Further, both the sponsor and FDA typically hold practice sessions (or “Mock Panels”) in the months leading up the panel.

In contrast with this trend, FDA has continued to hold general issues advisory committee meetings, primarily to discuss device safety issues. While the numbers have varied year to year, eight such meetings were held in 2019. These include a meeting in June 2019 to discuss a potential mortality signal associated with paclitaxel-coated balloons and eluting stents when used in peripheral arterial disease as well as a February 2019 meeting to discuss transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair.

Number of Device Panel Meetings Convened by FDA 2010–2019[2]

Panel Homework Assignments

Panel homework assignments allow FDA to obtain outside expertise on a smaller scale than a panel meeting, and with far fewer resources. Panel homework assignments are specific assignments made to experts who have been qualified as Special Government Employees (SGEs) that have been appointed as members of an advisory panel and as consultants to the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). Currently, the Medical Devices Advisory Committee is comprised of eighteen medical device panels, including the Medical Device Dispute Resolution Panel (DRP), consisting of a maximum of 159 standing members total. Further, the agency has a network of over 700 SGEs who can serve as temporary panel members and participate in homework assignments.[3] FDA can also tap into experts who are federal employees in other agencies, including the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), as they are subject to government ethics laws and are authorized to receive confidential information.

CDRH uses homework assignments to answer agency questions that do not require convening a full advisory panel. Homework assignments are conducted for review of marketing applications that do not need to be reviewed by a full panel (e.g., a PMA Supplement), review of an issue that may be considered as a potential topic at an upcoming advisory committee meeting, or review of a product early in its development. They may also be conducted for more targeted questions on product applications (e.g., review of a clinical safety outcome) or for more general purposes (e.g., assistance in developing a guidance document).

One to three SGEs are selected to complete homework assignments. A homework assignment to more than three members constitutes an advisory committee meeting; therefore, the limit of panel members completing homework assignments to date is three.[4] CDRH reported in 2017 that it utilizes 60 to 100 SGEs performing over forty homework assignments per year.[5] However, this number has not been updated in years—at least since 2011. In our experience, these homework assignments are being used more frequently in recent years. While less resource-intensive, CDRH has reported that it can take a similar amount of time to arrange a homework assignment as a panel meeting—in the range of three months.[6]

After identifying the participants, the agency sends the selected members a briefing package with specific questions and inquiries. The selected members review the materials and provide answers to the agency’s questions in writing. These answers are reviewed by FDA and form part of FDA’s review of the device.

Pros and Cons of Panel Homework Assignments

One of the advantages of utilizing panel homework assignments is a streamlined approach for accessing expertise. The agency will receive targeted subject-matter responses without the need to convene an advisory committee meeting. This in turn saves agency resources. Another advantage is that utilizing panel homework assignments theoretically has the potential to accelerate a device’s entry to market, bringing innovative technology and therapies to those that need it the most on a shorter timeframe; however, as noted above, this is not always the case in practice. Furthermore, homework assignments are not made public. Proprietary, confidential information regarding the device, as well as an advisory member’s opinion and responses, will not be made public. This provides a level of assurance to members and bolsters their ability to provide objective opinions on the device or issue under review and maintains privacy regarding information about the device and the company’s data, where this is desired.

On the contrary, the major disadvantage of utilizing homework assignments is a complete lack of transparency and involvement of the sponsor. FDA has total control over the selection of the SGEs involved, the briefing materials provided to the SGEs, and the types of questions and inquiries posed to the panel member. The sponsor often has no visibility on any of these items, and thus no ability to review or comment, contribute information, or respond to questions regarding their own data. We know of at least one instance where the sponsor was not even aware that a panel homework assignment had been conducted until after a final decision had been made by FDA on the device application and the company requested the summary basis of the decision. Further, the procedures and timeframe for review are ill-defined, and there is no visibility on the conflicts process for the SGEs involved. Another disadvantage is that “free and open participation”[7] by all interested persons is not an option. Panel homework assignments are not categorized as “meetings”—which would trigger public notice in accordance with 21 C.F.R. § 14.20—so this communication and the process is shielded from any other interested parties such as the sponsor, manufacturer, or other members of the public. Given the “remote” nature of panel homework assignments, as opposed to in-person meetings, the level of review by the SGEs can vary. While FDA does not publish detailed statistics on panel homework assignments, it is our experience that they may be less likely to result in a favorable outcome for the device sponsor than public advisory panel meetings.

It is widely accepted that the panel meetings to review device applications often result in a positive recommendation with regard to the device (e.g., positive risk-benefit ratio or approval). For example, in an analysis of the meetings of the Neurology Devices Panel to review device applications from 2000–2018, we found that ten out of eleven votes (91%) were favorable. While panel homework assignments are not directly comparable, as they are often limited to specific scientific questions or topics (rather than approval or overall risk/benefit ratio), our experience has been that these exercises are less likely to be favorable to the sponsor. This should be no surprise given the lack of balanced participation by the sponsor in homework assignments, which is only available at open panel meetings.

This lack of sponsor participation and visibility is in stark contrast to the openness and transparency of panel meetings. For example, under Section 513(b)(6)(A)(iii) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), sponsors are to have the same opportunity as the agency to participate in meetings of the panel. Section 513(b)(6)(B) of the FD&C Act requires that meetings encourage free and open participation by all interested persons. The briefing materials are posted online, the meetings (all or a portion of them) are open to the public, and all interested parties are given the opportunity to participate in the open public hearing portion of the meeting.

If FDA plans to rely on panel homework assignments more frequently, the agency should revise the process to allow the sponsor more participation in and visibility on the process. For example, sponsors could be given the ability to review and comment on the briefing materials and questions, or the ability to respond to questions by the experts about the sponsor’s data. One could argue that since the SGEs tapped to participate in homework assignments are essentially granted such authority under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), this process should be subject to the same transparency requirements as panel meetings.

In our experience, panel homework assignments can be advantageous to companies in certain limited situations where FDA and health care professionals in the field are in disagreement, for example, in instances where the sponsor or manufacturer of the device under review uses an endpoint in its clinical study that is recognized by clinical experts as the standard of care and FDA recommends an outdated, historical, or currently out-of-favor primary endpoint for the same clinical study. Another example of a situation in which a panel homework assignment may be beneficial is where FDA is imposing a higher safety or efficacy threshold than what is accepted in the clinical community. In such situations, panel homework assignments can provide FDA with an objective opinion on the safety threshold and clinical study design accepted in the industry.

In sum, panel homework assignments can most benefit companies in situations when the clinical community is more likely to agree with the company’s position than FDA’s position. However, since FDA controls the experts selected, and the sponsor has no opportunity to provide input into the process, the chances of the exercise favoring the company are lower.

What Next?

In recent years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person panel meetings to review new device applications were in decline, while the mechanism of panel homework assignments had become more prevalent.

It is unlikely that in-person panel meetings to review applications will disappear entirely, as agency policy is to review first-of-a-kind PMA products and Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE) products in front of a panel. FDA’s web site states: “In general, all PMAs for the first-of-a-kind device are taken before the appropriate advisory panel for review and recommendation.”[8] However, while this has been FDA policy, the regulations do not strictly require panel review. As stated in 21 C.F.R. § 814.116(a), “FDA may refer the PMA to a panel on its own initiative, and will do so upon request of an applicant, unless FDA determines that the application substantially duplicates information previously reviewed by a panel.” There is a parallel regulation for HDEs, although often HDEs do not go to panel. There was one advisory panel to review an HDE between 2010 and 2019, and twenty-six original HDEs were approved during that period. FDA’s panel procedures guidance states that “[w]hen acting at its own discretion, CDRH intends to consider taking a matter before a panel if, among other things, the matter is of significant public interest or there is additional or special expertise provided by the panel that could assist the Center in its decision-making” and notes examples where the agency would seek input on premarket submissions, including for novel technology or unexpected study results.[9]

However, given the flexibility in the regulations on when FDA can seek panel review of a device, the resources associated with convening an in-person meeting, and the societal gathering constraints resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, FDA may well turn even further to panel homework assignments, and possibly teleconference panel meetings, in the future.

As outlined in 21 C.F.R. § 14.22(g) and 21 C.F.R. § 814.44(b), panel meetings, including meetings to review a PMA, may be held virtually (e.g., by teleconference or videoconference). Historically, and per the regulations in 21 C.F.R. § 14.22(g), FDA holds limited virtual meetings for discussion topics that are anticipated to be brief, such as confirming recommendations from an in-person meeting, or when time does not permit a meeting to be held at a central location.[10] Further, FDA guidance specifies that, at minimum, the Panel Chair should be on location during the meeting, while other panel members can be remote.[11] However, with the impact that COVID-19 has had on the ability of teams to interact and work virtually, it is possible FDA will follow suit and rely more on virtual and teleconference meetings, such as the one held on May 8, 2020, by the Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee in order to fulfill agency meeting requirements. The meeting had a partially closed and an open session. Both of these sessions were held entirely virtually. During the open session, the Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee discussed updates on research, research programs, and regulatory activities in other Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) branches, including the Tumor Vaccines and Biotechnology Branch.[12] Historically, these meetings have been held in person. Notably, FDA held a teleconference meeting of the Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (pedsODAC) on June 17–18, 2020 to consider and discuss issues relating to the development of two products for pediatric use and provide guidance to facilitate the formulation of written requests for pediatric studies, if appropriate.[13] Further looking at the year 2020, thus far, the agency scheduled four device-focused panel meetings, two of which were scheduled in April and later postponed, one scheduled in June and rescheduled for September (virtually), and one scheduled in-person for October to discuss the PMA application for Neovasc Inc.’s Reducer device.[14]

Sources at FDA have indicated that the agency is currently taking measures to be able to conduct advisory committee meetings virtually. However, for meetings to review medical device applications, FDA indicated sponsors would have to agree to the format of the meeting prior to scheduling such a teleconference meeting. For general issue and classification meetings, no prior buy-in from stakeholders is necessary for the implementation of these changes. The public would continue to be able to participate in these meetings virtually, and sufficient information with respect to meeting times and registration would be communicated by FDA in the Federal Register. These procedures were confirmed with the release of a new guidance issued in June 2020 regarding the effect of COVID-19 on formal meetings with FDA.[15] FDA also indicated in discussions they are relying on panel homework assignments as needed, but did not confirm whether the agency had increased use of this process given the decline in in-person meetings.

FDA staff has also indicated that many sponsors and FDA staff would prefer in-person meetings, and thus the agency plans to resume in-person meetings following the end of the public health emergency. However, the public health emergency does not appear to be near its end. On July 25, 2020, the Secretary of DHHS once again renewed the public health emergency for another ninety days.[16] This is now the second renewal since the first declaration of a public health emergency issued on January 31, 2020, and there is a possibility this could last for years. Given the existing reduction in panel meetings to review device applications over the last several years prior to the public health emergency, it may well be that the effects of COVID-19, which are expected to linger for years, will continue to drive a further reduction in in-person panel meetings.

This trend may well not be to the advantage of medical device manufacturers. As described above, full-day teleconference meetings are not likely to have the same dynamic or be as productive as in-person meetings. Further, the prime disadvantage of utilizing homework assignments is a lack of transparency into the process and a lack of involvement of the sponsor. While panel homework assignments may benefit sponsors in certain situations where the experts are more inclined to agree with the company’s position, since FDA controls the experts selected and the information presented to those experts, and the sponsor has no opportunity to provide input into the process, in our experience, the exercise tends to favor FDA’s position rather than the company’s.

Given the decrease in in-person panel meetings in recent years, if FDA plans to rely on panel homework assignments more frequently, it is important that the agency revamp its procedures to allow the sponsor more participation and visibility on the process in order to ensure a fair and balanced process.

[1] Kristin and Sandra wish to thank Janice Hogan and Gerry Prud’homme, both partners in Hogan Lovells’ Medical Device and Technology Regulatory practice, for their input and advice regarding this article.

[2] Information contained in this table and graph represents a compilation of committee meeting information as contained in the meeting materials publicly available for each meeting held in the years 2010–2019, available at https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar.

[3] Network of Experts- Expert Utilization Standard Operating Procedure (DRAFT), available at https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cdrh-reports/network-experts-expert-utilization-standard-operating-procedure-draft (last accessed on June 18, 2020).

[4] United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Requesters, FDA Advisory Committees, Process for Recruiting Members and Evaluating Potential Conflicts of Interest, https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08640.pdf, pg. 50.

[5] Id. at 2.

[6] Id.

[7] Section 513(b)(6)(B) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) states that “[a]ny meeting of a classification panel with respect to the review of a device shall . . . encourage free and open participation by all interested persons.”

[8] “PMA Review Process,” FDA.gov, https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-approval-pma/pma-review-process.

[9] Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, Procedures for Meetings of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee (Sept. 1, 2017), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/91429/download.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Summary Minutes 68th Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee Meeting, May 8, 2020, available at https://www.fda.gov/media/138415/download.

[13] UPDATED AGENDA AND PUBLIC PARTICIPATION INFORMATION: June 17–18, 2020: Meeting of the Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (pedsODAC), available at https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/updated-agenda-and-public-participation-information-june-17-18-2020-meeting-pediatric-oncology.

[14] Advisory Committee Calendar, FDA.gov, https://www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar (last accessed on June 18, 2020).

[15] Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, Effects of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency on Formal Meetings and User Fee Applications for Medical Devices—Questions and Answers (June 2020), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/139359/download.

[16] Renewal of Determination That A Public Health Emergency Exists, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, available at https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions/phe/Pages/covid19-23June2020.aspx.

Update Magazine

Fall 2020