FDA Data Integrity Enforcement Trends and Practical Mitigation Measures

by Barbara Unger

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) identified failures in data governance and data integrity starting approximately 20 years ago. Enforcement actions associated with these issues have increased since they initially appeared and are now at the forefront of highly visible FDA enforcement actions. This article provides a brief history of enforcement in the area, discusses enforcement trends and current FDA enforcement actions, and provides suggestions for how firms can prevent and remediate data integrity deficiencies.

History of Enforcement for Data Integrity and Data Governance

The “generics scandal” of the 1980s identified falsified data submitted to FDA in support of Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) approvals. One outcome of this scandal was the shift in focus of FDA pre-approval inspections (PAI) to evaluating raw laboratory data included in the marketing application and assessing whether the site was capable of manufacture as described in the application.

In parallel, FDA recognized the increased reliance on computerized systems within the pharmaceutical industry. FDA developed and published 21 CFR 11 and its preamble, the final rule on Electronic Records and Electronic Signatures in 1997. In 2003, FDA published “Guidance for Industry, Part 11, Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures – Scope and Application” to address enforcement priorities. Further guidance on FDA interpretation can be found in compliance actions such as forms 483 and warning letters, podium presentations, and FDA’s GMP Q&A web page.

As early as 2000, a warning letter issued to Schein Pharmaceuticals cited lack of control over computerized laboratory systems including lack of password control, deficiencies in system design, configuration, and validation, as well as broad-ranging staff authority to change data. In 2005, FDA issued a 15-page form 483 to Able Laboratories in New Jersey. (See FEI No. 3004106764). The inspection observations cited the firm for submission of false data to FDA and failure to review electronic data including audit trails. FDA also issued three warning letters to two Ranbaxy sites in 2006 and 2008 that included data integrity deficiencies. (See WL 320-06-03, WL 320-08-02 and WL320-08-03)

Following these compliance actions, FDA announced a pilot program in 2010 to evaluate data integrity as part of routine GMP inspections. FDA Investigator Robert Tollefsen described the program in presentations at a number of industry conferences in 2010. FDA stressed that it would “continue to enforce all predicate rule requirements, including requirements for records and recordkeeping.” In fact, deficiencies in Part 11 are rarely, if ever, cited in warning letters; almost all deficiencies are failures to comply with predicate rules. Findings of shortcomings in this area do not represent a new approach by FDA to interpreting existing rules or imposing new requirements.

FDA is not unique in establishing and updating requirements and guidance regarding data management to ensure data integrity. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) revised and expanded Annex 11 of the EU GMP Guide in 2011 to provide additional clarification for computer system requirements. The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) took the lead in the EMA region to identify and detail requirements for data integrity beyond the requirements of Annex 11. In December 2013 MHRA announced that the pharmaceutical industry is expected to review data integrity during self-inspections and published its current guidance document on the subject in March 2015.

Trends in Enforcement

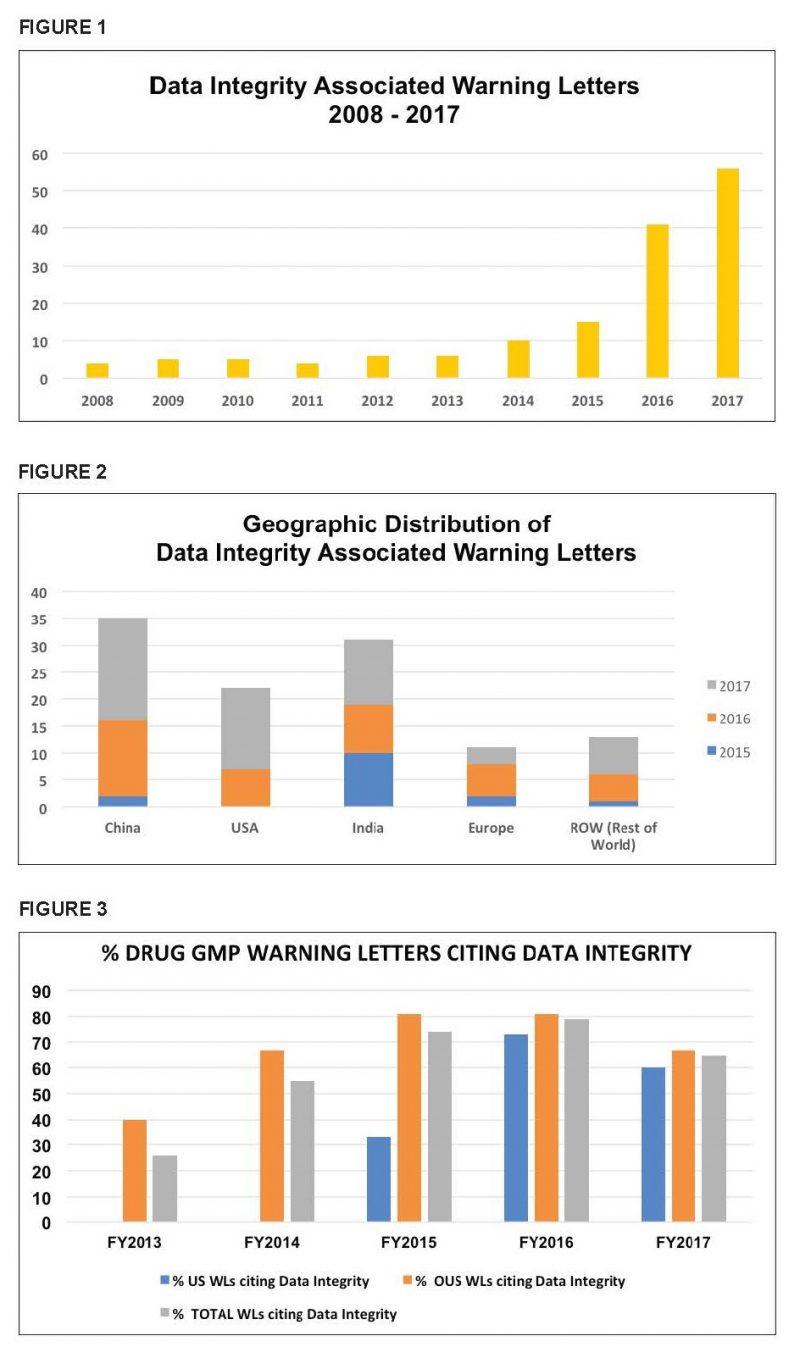

An analysis of enforcement trends shows that the number of warning letters citing deficiencies in data integrity increased markedly beginning in 2014 and continuing through 2017. (See Figure 1)

Figure 2 shows that sites in China were the subject of the most warning letters involving data integrity issues in the past three years, followed by sites in India and the United States, Europe, and the rest of the world (ROW). (ROW in 2015-2017 include Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, Singapore, South Korea, and Thailand.) China, India, and the United States account for approximately 80% of all warning letters in this category over the past three calendar years. (See Figure 2)

Figure 3 shows the percentage and distribution of these warning letters per fiscal year between 2013 and 2017. (Figure 3 presents data for FYs rather than the CYs as above which explains slight variations in the data.) It is interesting to note that the percent of warning letters that cite data integrity deficiencies issued to U.S. sites in FY2016 and FY2017 is very similar when compared to warning letters issued outside the U.S.

Frequently Identified Deficiencies

Deficiencies identified by FDA remain surprisingly consistent and suggest the continuing failure of firms to address fundamental GMP requirements. Two regulations frequently cited by FDA are 21 CFR 211.68 and 21 CFR 211.194.

Section 211.68 specifies the requirements for “Automatic, Mechanical and Electronic Equipment.” Deficiencies in this area occur for example, when:

- A firm fails to implement adequate controls over computer systems to ensure that only authorized individuals have access to the systems.

- Individuals’ access is not consistent with their roles and responsibilities. For example, warning letters have identified instances where laboratory analysts can delete or modify data and change configuration settings such as disabling audit trails.

- Electronic data are not subject to backup and retention so that activities can be reconstructed in the future, if necessary.

- Laboratory analysts can adjust date and time stamps for electronic data to falsify the date/time when data was initially acquired.

- Data in audit trails do not match the data in the printed chromatograms.

FDA cites §211.194 when firms do not review all data and include it in making lot release decisions, including for example:

- Failure to review electronic data, including critical meta-data, when electronic systems generate and store data. For example, firms may review a printed chromatogram without considering the need to review raw electronic data and critical meta-data. Of particular concern is the possibility of failure to identify out of specification (OOS) events that require investigation and consideration in lot release decisions.

- The firm falsifies analytical test results, destroys data, or the firm does not have data to support an analytical test result.

- Analysts reprocess or manipulate data until results meet acceptance criteria and delete the potential OOS data.

In the past few years, FDA has increased the scope of the deficiencies identified as the agency has become more proficient at understanding electronic laboratory systems. Recently identified deficiencies include, for example:

- The practice of using “pre-injections” of product samples outside of full samples sets with the apparent intent to determine whether results pass acceptance criteria. If results fail, they are ignored or deleted.

- Intermittently disabling audit trails to obscure results; deletions or modification of results.

- Inappropriate use of integration suppression settings to minimize problematic data that would likely result in either an OOS event or the need for an investigation.

- Aborting analytical test runs without explanation or justification.

Actions Firms Can Take to Identify and Mitigate Problems

Recognizing FDA’s data integrity emphasis and understanding the common gaps, firms can prevent, identify, and remediate problems in this area. In the long term, prevention of problems is the goal, but identification and remediation of gaps should receive immediate attention. Detection, remediation, and prevention activities should be cross-functional and include IT, QA, QC, and other stakeholders as necessary. Firms should take action in these three areas: executive management, technical areas, and oversight of vendors and contract organizations.

Management Responsibilities:

- Management must develop and sustain a corporate culture where reporting of mistakes is encouraged without retaliation. This approach speaks to the importance of a culture of quality.

- Management should ensure that a process is in place to ensure that data is valued as a corporate asset and ensure that it is accurate, trustworthy, and secure throughout its lifecycle.

- Staff should receive education on the fundamental concepts of data integrity and its importance. Everyone who touches a GMP record plays an important role and contributes to the success of the organization.

- Management should ensure a fair and unbiased process is in place to investigate potential data integrity breaches and ensure the confidentiality of any employee who comes forward with information.

- Firms should ensure they are aware of GMPs and their enforcement. FDA’s transparency in the publication of forms 483 and warning letters ensure that firms can learn from the mistakes of others. Warning letters and forms 483 are among the best training materials available for little or no cost.

- Firms should also be aware that data integrity applies to both paper and electronic records and this regulatory initiative will not “go away.”

- Remediation is often costly and time-consuming. It is rarely accomplished in a few months but is often a multi-year process. Firms often identify additional gaps during the remediation process.

Technical Area Responsibilities:

- Identify gaps between company practices and procedures and the regulation/guideline requirements and health authority enforcement actions. Prioritize remediation based on risks to product quality and patient safety. Develop a timeline and track items to completion. Identify and implement interim controls pending full implementation of compliant solutions.

- Remember to start with the fundamentals when performing gap assessments. For example, a firm should identify what constitutes original data and the controls for data generation, processing, review, approval, and back-up / archival processes.

- Validate computer systems for their intended use including the ability to identify invalid, altered, or deleted records. Computer system validation is not sufficient as procedural controls must be put in place to specify other aspects of control including, but not limited to, data generation, processing, review, and security.

- Functional areas should map data and process flows for all GMP computer systems including enterprise systems, laboratory systems, and manufacturing systems. This information can be used to identify points of risk and implement remediation.

Contract Operations and Suppliers:

Firms should remember that evaluation and remediation of their quality systems must include efforts to ensure that contractors and suppliers have adequate programs in place.

21 CFR 200.10(b) states “The Food and Drug Administration…regards extramural facilities as an extension of the manufacturer’s own facility.” The FDA guidance on Contract Manufacturing Arrangement for Drugs: Quality

Agreements states that contract analytical laboratories must “…employ adequate controls to ensure that data and test results are reliable and maintained in accordance with CGMP requirements. It is the owner’s responsibility to review this information from the contract facility to decide whether to approve or reject product for release and distribution.”

Adequate Contract Site Oversight Requires a Multi-Dimensional Approach:

- Rigorous due diligence evaluation includes:

- Understanding computer system validation and controls including but not limited to adequate user requirements, configuration specifications and testing of both.

- Assurance that systems are validated for their intended purpose with processes and procedures to permit identification of altered or deleted data.

- Confirmation that access to systems is limited to authorized personnel and the extent of the access is consistent with roles and responsibilities.

- SOPs are in place to ensure that staff conduct data reviews in the medium under which data was collected. For most laboratory systems, this requires a review of electronic data and critical meta-data. Reviewers should have adequate training in the review process.

- The Quality Agreement should document roles and responsibilities and include the following:

- A requirement that the partner ensures the trustworthiness of data throughout its lifecycle, in both paper and electronic form, consistent with GMP requirements.

- The contract grantor is permitted to review electronic data.

- When transferring data between partners, the agreement should specify how to perform this activity in a way that ensures integrity and completeness of the data.

- The sponsor should continually evaluate its contract sites for health authority inspections or other enforcement actions.

- Firms should seek forms 483 for inspections of all sites owned by their contractor, not merely follow inspections of the site where the contractor performs the sponsor’s activities. Problems are often systemic, and FDA identification of concerns at a particular site may indicate issues that the sponsor should evaluate at the site in question.

- Firms should monitor recalls and import alerts. FDA has cited firms in warning letters for the use of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) acquired from a firm that is under FDA Import Alert.

Conclusion

FDA has identified failures in data governance and data integrity in 60-80% of pharmaceutical warning letters issued to both domestic and foreign sites over the past three years. Enforcement in this area is not new for FDA, and other global health authorities now address this area in inspections. Deficiencies identified in warning letters continue to cite remarkably similar practices over the past 20 years. These include computer systems not validated for their intended purpose, lack of controls over computerized systems to prevent access by unauthorized users and failure to evaluate all original data, including audit trails, generated in testing and to consider the results as part of the lot release decisions.

Health authority regulations and guidance provide clear expectations for this area and are widely available. Enforcement actions, particularly those taken by FDA, are publicly available and are superb tools for understanding expectations and in the education of staff. Rx-360, an International Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Consortium focused on supply chain security, developed and published a data integrity library that includes global regulations and guidance, slide presentations given by regulatory authorities, and an extensive collection of articles on the many aspects of data governance and data integrity. It behooves firms to take advantage of such publicly available information to guide efforts in implementing compliant data governance and data integrity processes.

Update Magazine

March/April 2018