Prescription Drug Advertising and Promotion Regulations and Enforcement in Select Global Markets

by Upasana Marwah, Dana Huettenmoser, and Sheetal Patel

The Pharmaceutical Industry is a constantly growing global market. The worldwide market for pharmaceuticals is projected to grow to $1.3 trillion by 2020, representing an annual growth of 4.9 percent. There are several different global demographic and economic trends that are driving the pharmaceutical market, including a rapidly aging world population and an associated rise in chronic diseases, increased higher disposable incomes, greater government expenditure on healthcare and growing demand for more effective treatments.1

In an effort to promote and educate patients and health care professionals on treatment options, the pharmaceutical industry, like many other industries, dedicates billions of dollars to advertising and promotion of prescription drugs. In 2015, the total global investment of the pharmaceutical industry in prescription drug promotion was $69.2 billion dollars, which was up 3.4 percent from 2014.2

In an effort to promote and educate patients and health care professionals on treatment options, the pharmaceutical industry, like many other industries, dedicates billions of dollars to advertising and promotion of prescription drugs. In 2015, the total global investment of the pharmaceutical industry in prescription drug promotion was $69.2 billion dollars, which was up 3.4 percent from 2014.2

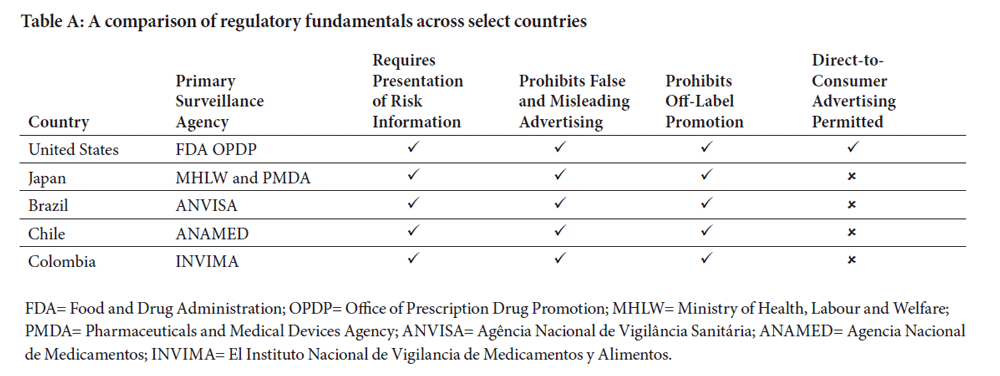

In the United States, many laws and regulations govern prescription drug advertising and promotion. The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) reviews prescription drug advertising and promotional labeling to ensure the information contained in these promotional materials is not false or misleading.3

Like the United States, some countries have provided guidance to the industry with regard to regulatory requirements of prescription drug advertising and promotion. On the other hand, some countries have few resources focused on prescription drug advertising and limited resources for the surveillance of prescription drug advertising.

This article will provide a general overview of the regulatory framework of prescription drug advertising and promotion in select countries, including Japan, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. In addition, a brief overview of prescription drug advertising and promotion regulations in the United States of America is included to provide a benchmark for comparison.

The United States of America

In the United States, prescription drug advertising and promotion is monitored by FDA’s OPDP. OPDP reviews prescription drug advertising and promotional labeling to ensure the information contained in these materials is not false or misleading. The mission of OPDP is “to protect the public health by assuring prescription drug information is truthful, balanced, and accurately communicated. This is accomplished through a comprehensive surveillance, enforcement, and education program, and by fostering better communication of labeling and promotional information to both health care professionals and consumers.”3

Prescription Drug Promotion Regulations

In the United States, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations Part 202 (21 CFR Part 202) primarily govern prescription drug advertising and promotion. Together, the FDCA and 21 CFR Part 202 regulate how pharmaceutical companies can promote prescription drugs to both health care professionals and consumers. In addition to laws and regulations, FDA has issued draft and final Guidance documents, which help provide their current thinking on several topics related to prescription drug promotion.3,4

Failure to adhere to certain requirements of the FDCA may deem a drug to be misbranded. Per FDA regulations, all prescription drug promotion must:

- be consistent with the FDA approved Prescribing Information (PI);

- be truthful and non-misleading;

- contain a fair balance of product benefits and risks; andinclude material information.

One of the fundamental requirements of prescription drug promotion in the United States is the requirement that companies promote only uses that are “on label” or consistent with the FDA-approved PI. The term “off label” generally refers to promotion of a product for uses that are inconsistent with the FDA-approved labeling or PI. This can relate to the promotion of uses, dosing/administration, or patient populations that are not FDA-approved.3

Another requirement is that promotional materials must not be false or misleading. There are many ways that promotional materials can be deemed false or misleading, including promotion that somehow characterizes a drug to be more effective or safe than what is supported by the FDA-approved label.

Furthermore, all promotional materials that include efficacy/benefit claims must provide fair balance between benefit information and information on risks associated with the product. Fair balance not only refers to the inclusion of the safety information but also to the overall prominence of its presentation as compared to the benefit presentation. Promotional materials that do not present the benefits and risks in a fair and balanced manner could be deemed as false or misleading.3

Prescription drug promotion may also be considered false and misleading if there is a failure to include material information. Material information refers to anything that may be critical for a patient or health care provider to know before or while using a drug that would help ensure safe and effective use of the product.3

Surveillance and Consequences of False and Misleading Promotion

OPDP reviews promotional materials submitted at the time of initial dissemination on Form FDA 2253, as well as through routine surveillance and the Bad Ad Program. Subpart H drugs designated for accelerated approval follow a different process outside the scope of this article. The Bad Ad Program seeks to raise awareness among health care professionals regarding false and misleading promotion and provides a venue to report violations or misleading promotional materials to the OPDP.3 If it finds materials to be violative, OPDP can issue two different types of letters. The first and less serious type is called an Untitled Letter, also known as Notice of Violation (NOV), which usually requires that a company cease the offending promotions. The second type is called a Warning Letter and can result in a company also being required to do corrective advertising, which can be laborious and costly. Both types of letters identify the various violations OPDP has found in the promotional materials, which often include false or misleading risk presentation, false or misleading benefit presentation, and lack of adequate directions for use.3

In 2016, OPDP issued a total of 11 letters, eight Untitled Letters and three Warning Letters. Of the 11 letters, four related to investigational new drugs that had not yet been approved by FDA. The violative promotional materials at issue in four of these letters were detected via Form FDA 2253, while seven were captured through routine monitoring and surveillance. A primary violation noted in over half of the 2016 OPDP letters was that the promotional materials contained a false or misleading risk presentation or omitted risk information. Other violations included omission of material facts, false or misleading benefit presentations, failure to submit under Form FDA-2253, and lack of adequate directions for use.3

Voluntary Codes

In addition to laws and regulations, there are voluntary industry organizations such as the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) where member companies may adopt codes and guidelines.5,6

Japan

In Japan, prescription drug advertising and promotion is primarily regulated and monitored by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). However, prefectural governments, like the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, are primarily responsible for overseeing pharmaceutical companies on behalf of the MHLW. In addition to the MHLW, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), a regulatory agency like FDA, also monitors prescription drug advertising and promotion.7,8

Prescription Drug Promotion Regulations

In Japan, the MHLW prohibits prescription drug advertising and promotion to consumers. However, disease awareness advertising and promotion to consumers is permitted, so long as there are no product or brand mentions included within the advertising.7,9

The Pharmaceutical Affairs Act Articles 66-68 provide three considerations for prescription drug advertising to health care professionals: 7,10

- Prescription drug advertising and promotion may not be false or misleading. Thus, promotional materials may not make false or exaggerated statements regarding the indications, effects, or properties of prescription drugs;

- Representations depicting abortion or obscenities with respect to drugs is prohibited; and

- Prescription drug advertising and promotion of drugs prior to their approval is prohibited.

Surveillance and Consequences of False and Misleading Promotion

The MHLW and PMDA are the two regulatory agencies that are primarily involved in the surveillance and enforcement of prescription drug advertising and promotion. If a company breaches the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, it could be subject to fines, imprisonment, business suspension, or an order to improve business operation.11

In 2015, the MHLW filed a criminal complaint against a global pharmaceutical company relating to an investigation into the pharmaceutical company’s local unit. The MHLW alleged that the company manipulated data and exaggerated advertising of its prescription drugs. As a result, the company was ordered to conduct a 15-day business suspension, requiring it to halt manufacturing and sales of all prescription drugs for those 15 days.12,13

In 2015, another global pharmaceutical company received an order to improve business operations from the MHLW. The order was based on the decision that two promotional materials targeting healthcare professionals were deemed to be misleading. The order alleged that the company inappropriately emphasized efficacy claims in promotional materials for healthcare professionals regarding secondary effects of the medicine. The order came after a physician in Japan pointed out that an ad for the company’s drug contained data that didn’t match the results of a clinical study. Upon further investigation, it was found that the ad suggested that the drug was more effective than a competitor, even though the clinical trial results indicated no discernible difference. The company responded that the ad contained a graph that had been presented during an academic conference rather than data showing the results of the head-to-head clinical trial. As a result of these findings, the MHLW requested that the company strengthen its review system for promotional materials and enhance the training program for employees and senior managers responsible for the process of developing and reviewing materials in Japan.11,14

Voluntary Codes

The Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA) and the Japan Federation of Pharmaceutical Organizations (JFPO) are two examples of voluntary associations that provide guidance on prescription drug promotion and other activities of pharmaceutical companies through their respective codes.15, 16

Brazil

In Brazil, the Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA), also known as National Sanitary Surveillance Agency, monitors and regulates prescription drug advertising and promotion. Although ANVISA is connected to the Ministry of Health, the regulatory agency is characterized by its administrative independence, financial autonomy, and the stability of its directors. The agency was enacted in 1999 by Law 9782 and is ruled by a Collegiate Board of Directors, composed of five members. ANVISA’s primary goal is to protect and promote public health by exercising health surveillance over products and services, including processes, ingredients, and technologies that pose any health risks.17

Prescription Drug Advertising and Promotion Regulations

In Brazil, the Federal Constitution consists of certain laws that govern prescription drug advertising and promotion. Fundamentally, the law states that medications that require a medical prescription can only be advertised to healthcare professionals who can prescribe (doctors or dentists) or dispense (pharmacists) medications. In order to market a drug, the product must be registered with ANVISA. Drug advertisements must also present complete, clear, and balanced information. Thus, it would be inappropriate for an advertisement to only highlight beneficial aspects of the product, when it is known that drugs are associated with risks inherent to their use.17,18

The law also states certain elements that must be included within the advertisement. These elements may include the trade name of the medicinal product, the name of the active substance, the registration number in ANVISA, the indication of the medicinal product, and the mandatory warning required by law: “If symptoms persist, consult a doctor.” Additionally, depending on the active substance or the effect indicated in the package leaflet registered by ANVISA, three additional warnings may be required: 17,18

- If a drug is associated with sedation or drowsiness, the following warning should be included: “Trade name of the product” is a medication. During your use, do not drive vehicles or operate machines, as your agility and attention may be impaired.”

- The second warning relates to an active substance of the medicinal product and use in children. For example, a warning could be, “Cancer: Do not use this medicine in children under two years of age.”

- The third warning is a standard warning that may be applicable to all drugs. “(Trade name of the medicinal product) is a medicinal product. Your use of [the product] can cause risks. See a physician and pharmacist. Read Prescribing Information.”

Surveillance and Consequences of False and Misleading Promotion

ANVISA is the primary regulatory agency involved in the surveillance of prescription drug advertising and promotion. There are various consequences of breach in Brazil including: 17,18

- warnings

- fines

- product apprehension/destruction/interdiction

- suspension of sale/manufacturing

- partial or complete interdiction of company

- prohibition of advertising

- cancellation of the operation authorization

- criminal and civil liabilities

Voluntary Codes

There are various voluntary trade organizations in Brazil and Latin America that pharmaceutical companies may choose to join. Some examples of these organizations include Interfarma and the Pan American Network on Drug Regulatory Harmonization (PANDRH). PANDRH is an example of an organization that strives to provide a forum for improving public health in the Americas and a consistent code of conduct for members.19,20

Chile

In Chile, prescription drug advertising and promotion is monitored and regulated by the Agencia Nacional de Medicamentos (ANAMED), also known as the National Drug Agency. ANAMED is part of the Institute of Public Health (ISP) and is responsible for the control of pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and medical devices, guaranteeing their quality, safety and effectiveness.21 ANAMED grants sanitary authorizations and registration of pharmaceutical and cosmetic medicines, in addition to exercising an active surveillance and enforcement of applicable regulations.22

Prescription Drug Promotion Regulations

In Chile, prescription drug advertising and promotion is governed by multiple bodies of law. Provisions include the Health Code (Decree with Force Law No 725), Law 20,724 and Decree No. 3. In addition, there are decrees that regulate narcotic drugs (Supreme Decree No. 404) and psychotropic drugs (Supreme Decree No. 405). 23,24

While many of these provisions overlap, they provide the fundamental regulatory guidance for prescription drug advertising and promotion. Rules and regulations include the following: 25-28

- All drugs must have received sanitary authorization prior to marketing.

- All product promotion regarding the direct sale of pharmaceutical products must obtain marketing authorization from the ISP.

- All promotion must be in line with the therapeutic uses, indications, and properties approved when the sanitary registration was issued.

- Promotion must only be directed to those authorized to prescribe and dispense. Therefore, direct-to-consumer advertising is not permitted.

- All prescription drug promotion must include the formula, indications, interactions, contraindications, precautions, warnings, adverse reactions, side effects, dosage, and risk of toxicity and its treatment.

- Advertising and promotion must be truthful, accurate, complete, and verifiable.

- Prescription drug advertising and promotion must not deceive or cause harm to the public.

- Exaggerated claims are considered misleading and are strictly prohibited.

Surveillance and Consequences of False and Misleading Promotion

ANAMED is responsible for surveillance and enforcement of applicable regulations of prescription drug promotion. Any violations of the prescription drug advertising and promotion regulations may compromise public health. If ANAMED suspects possible infringements of the prescription drug advertising and promotion regulations, it may order administrative inquiries. If a breach of the regulations is confirmed, the pharmaceutical company may be sanctioned with the following:27

- fines

- suspension or prohibition of advertising and promotion

- cessation of work

- closure of facilities

- cancellation of operating licenses or permits granted

- confiscation or destruction of products

- criminal or civil liabilities

Voluntary Codes

Cámara de la Industria Farmacéutica de Chile (CIF), also known as the Chamber of Pharmaceutical Innovation of Chile, is an example of a local voluntary trade organization that provides guidance on the activities of pharmaceutical companies.29 Some companies may also choose to join regional and international trade organizations, such as the PANDRH.20

Colombia

In Colombia, prescription drug advertising and promotion is monitored by El Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos (INVIMA) also known as the National Drug and Food Surveillance Institute. INVIMA is responsible for inspecting and supervising the marketing and manufacturing of health products, identifying violations of the regulations, implementing best practices, and providing prescription drug marketing authorization. Their mission is to “protect and promote the health of the population by managing the risk associated with the consumption and use of food, medicines, medical devices, and other products subject to health surveillance.”30

Prescription Drug Promotion Regulations

In Colombia, prescription drug advertising and promotion is governed by Decree 677, Law 1480 (The Consumer Protection Law), and Law 256 (The Unfair Competition Law).31-33

The fundamental regulatory guidance for prescription drug advertising and promotion include: 31,32

- Prescription drugs can only be advertised through specialized publications intended for healthcare providers. Prescription drug advertising through mass media or direct to consumer advertising, such as through the radio or television, is strictly prohibited.

- All advertising and promotion must be truthful and not exaggerated or misleading.

- Information included in prescription drug advertising and promotion must include the mechanism of action, indications, therapeutic uses, contraindications, side effects, administration risks, risks of drug dependence, and other precautions and warnings.

- A pharmaceutical company may not omit any risk information stated in the scientific literature or those known by manufacturers.

Surveillance and Consequences of False and Misleading Promotion

INVIMA is responsible for regulating prescription drug promotion in Colombia. There are various consequences for noncompliance with regulations, such as:31

- notices

- fines

- suspension of activities or services

- seizure or destruction of products

- suspension of the sales rights

- suspension or cancellation of health registration

- temporary or final closure of facilities

- civil and criminal liabilities

Voluntary Codes

Asociación de Laboratorios Farmacéuticos de Investigación y Desarrollo (AFIDRO), also known as the Private Association of R&D Pharmaceutical Companies, is an example of a local voluntary trade organization that provides guidance on the activities of pharmaceutical companies.34 Some companies may also choose to join regional and international trade organizations, such as the PANDRH.20

Conclusions

While some countries have an abundance of laws and regulations governing prescription drug advertising and promotion, others provide minimal guidance. However, it can be noted that most of the countries sampled, contrary to the United States, prohibit prescription drug advertising and promotion direct-to-consumers.

Additionally, most countries have taken a similar approach in requiring that prescription drug advertising and promotion be truthful and non-misleading. While most countries prohibit false and misleading promotion, the consequences of noncompliance vary from country to country.

Additionally, it is important to note that while some countries may not have as detailed regulations related to prescription drug advertising, many companies voluntarily self-regulate by joining industry groups that promote ethical promotional practices and abiding by voluntary codes of conduct adopted by such groups. Many of these coalitions span across multiple countries or regions of the world with a common goal of encouraging responsible practices to help ensure patient safety.

As the pharmaceutical industry continues to grow and the demand for scientific advancements increases, countries may need to re-evaluate their regulatory framework to help ensure it is current and effective.

- 2016 Top Markets Report Pharmaceuticals. International Trade Administration. http://trade.gov/topmarkets/pdf/Pharmaceuticals_Executive_Summary.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Channel Dynamics Global Reference: An Annual Review of Pharmaceutical Sales Force and Marketing Channel Performance. Market Insights. http://www.imshealth.com/files/web/Market%20Insights/Channel%20Dynamics/IMSH_.

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. About the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research – The Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP). U S Food and Drug Administration Home Page. https://www.fda.gov/aboutfda/centersoffices/officeofmedicalproductsandtobacco/cder/ucm090142.htm. Published January 19, 2017. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- 21 CFR 202.1 https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=202.1. Accessed July 31, 2017.

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA. http://www.phrma.org/. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Healing, Fueling, and Feeding the World. BIO. https://www.bio.org/. Published 2017. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- PMDA Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. http://www.pmda.go.jp/english/. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Consumer Updates – Keeping Watch Over Direct-to-Consumer Ads. U S Food and Drug Administration Home Page. https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm107170.htm. Accessed June 27, 2017.

- Pharmaceutical Affairs Act. Ministry of Health, Labour, Welfare.

- Weintraub A. Takeda fesses up to improperly marketing its blood-pressure blockbuster, Blopress. FiercePharma. http://www.fiercepharma.com/sales-and-marketing/takeda-fesses-up-to-improperly-marketing-its-blood-pressure-blockbuster. Published March 4, 2014. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Novartis Japan says ordered to halt business March 5-19. Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/novartis-japan-idUSL4N0W12D320150227. Published February 27, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Japan files criminal complaint against pharma giant. World Finance. https://www.worldfinance.com/strategy/legal-management/japan-files-criminal-complaint-against-pharma-giant. Published February 18, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Takeda’s Statement on the Order Issued by the Japanese Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare regarding the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Act. Takeda – Better Health, Brighter Future. https://www.takeda.com/newsroom/newsreleases/2015/takedas-statement-on-the-order-issued-by-the-japanese-ministry-of-health-labour-and-welfare-regarding-the-pharmaceutical-and-medical-device-act/. Published June 12, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, “Promotion Code in Ethical Pharmaceutical Drugs,” Amended 19 March 2008 (Implemented 23 May 2008).

- The Japan Federation of Medical Devices Association, “Promotion Code in the Medical Devices Industry,” Amended 30 June 2010 (Implemented 1 October 2010).

- Contact us – Anvisa. Go to ANVISA. http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/en/contact-us. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Kung A, Kesselring J. Commercialization of Healthcare in Brazil: Overview. Westlaw Signon. https://content.next.westlaw.com/Document/Iaa1b36f9312c11e598dc8b09b4f043e0/View/FullText.html?originationContext=document&transitionType=DocumentItem&contextData=%28sc.Default%29&firstPage=true&bhcp=1. Published March 1, 2017. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Associação da Indústria Farmacêutica de Pesquisa. Interfarma. https://www.interfarma.org.br/. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- Home – Pan American Health Organization. www.paho.org. Accessed June 4, 2017.

- The International Association of National Public Health Institutes. Chile. http://www.ianphi.org/membercountries/memberinformation/chile.html. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- Institute of Public Health of Chile. Who We Are. http://www.ispch.cl/anamed_/quienessomos. Accessed June 7, 2017.

- Institute of Public Health of Chile. Regulations. http://www.ispch.cl/anamed/regulaciones. Accessed June 11, 2016.

- The Government of Chile. Regulatory Framework. http://transparencia.redsalud.gov.cl/transparencia/public/isp/marconormativo.html. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The Library of the National Congress of Chile. Health Code. https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=5595>. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The Library of the National Congress of Chile. Amended Decrees. http://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1084995. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The Library of the National Congress of Chile. Modified the Health Code in the Matter of Regulation of Pharmacies and Medicine. http://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1058373&idParte=>. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The Library of the National Congress of Chile. Decree No. 3. https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1026879&idParte=0. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- Chamber of Pharmaceutical Innovation of Chile. About Us. http://www.cifchile.cl/camara-de-la-innovacion-farmaceutica-de-chile/. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The National Drug and Food Surveillance Institute. Mission and Vision. https://www.invima.gov.co/nuestra-entidad/mision-y-vision.html.

- The National Drug and Food Surveillance Institute. Medication Decrees. https://www.invima.gov.co/decretos-en-medicamentos.html?start=20. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The Congress of the Republic of Colombia. Law 1480 of 2011 http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_1480_2011.html>. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- The Congress of the Republic of Colombia. Law 256 of 1996. http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_0256_1996.html. Accessed June 11, 2017.

- International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. Code of Ethics AFIDRO 2015. http://www.ifpma.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/01/Code_of_Ethics_AFIDRO_2015_English.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2017.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed herein are of the authors and in no way represent the views and policies of the authors’ past and present affiliations. The information in this publication is of the nature of general comment only and is not an exhaustive presentation of the rules and regulations of the respective countries. It is not offered as advice and no reader should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any matter contained in this publication without seeking specific professional advice.

Update Magazine

July/August 2017