“Consistent Communications”: FDA’s Incremental Expansion of Promotional Bounds

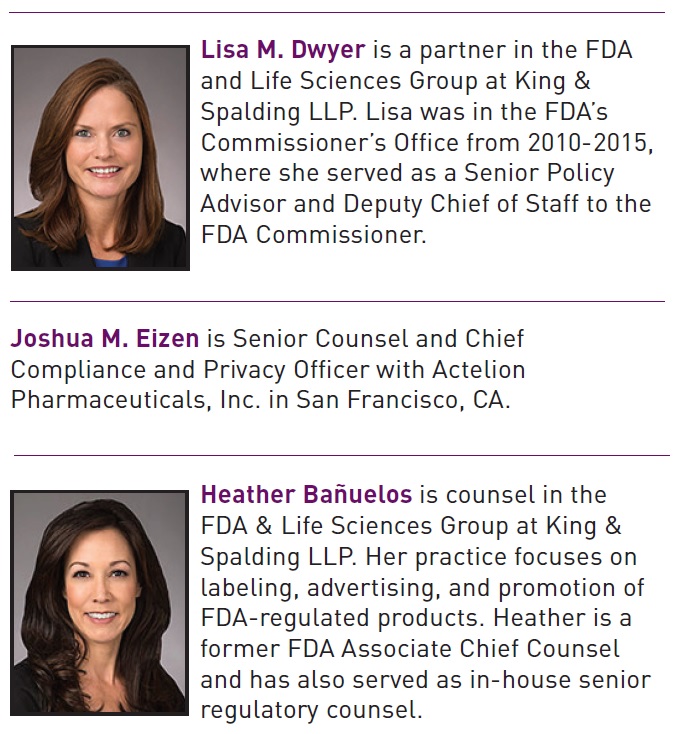

by Lisa M. Dwyer, Joshua M. Eizen, and Heather Bañuelos

Earlier this year, FDA expanded the bounds of medical product promotion and advertising by announcing a new policy regarding communications that are “consistent” with, but not contained in, FDA-required labeling for medical products. This new policy was articulated in a draft guidance, entitled Medical Product Communications That Are Consistent With the FDA-Required Labeling – Questions and Answers1 (Consistent Communications Guidance). According to the draft guidance, the agency will not consider communications that are “consistent” with FDA-required labeling, alone, to be evidence of a new intended use. The draft guidance was issued in the final days of the Obama Administration as one in a series of documents addressing manufacturer communications about medical products.

The practical significance of the draft guidance is two-fold. FDA recognized for the first time, conceptually, that not all manufacturer communications involving information beyond the four corners of FDA-required labeling are “off-label.” FDA also recognized that the scientific standard for approval—in the case of drugs for example, “substantial evidence”—is no longer the standard for promotion. Now, for promotion, “scientifically appropriate and statistically sound” evidence is sufficient, so long as the communication is truthful and “consistent” with the FDA-required labeling.

The practical significance of the draft guidance is two-fold. FDA recognized for the first time, conceptually, that not all manufacturer communications involving information beyond the four corners of FDA-required labeling are “off-label.” FDA also recognized that the scientific standard for approval—in the case of drugs for example, “substantial evidence”—is no longer the standard for promotion. Now, for promotion, “scientifically appropriate and statistically sound” evidence is sufficient, so long as the communication is truthful and “consistent” with the FDA-required labeling.

These were relatively easy concessions on FDA’s part, especially when viewed against the backdrop of government losses in First Amendment lawsuits, along with the likelihood, post-election, of a conservative Supreme Court. The agency did not answer the more difficult questions regarding proactive communications about “off-label” uses—such as in what circumstances FDA will consider “off-label” communications to be evidence of a new intended use, as opposed to scientific exchange. Nonetheless, the Consistent Communications Guidance is a meaningful step forward.

Background

Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), FDA can regulate products as drugs, devices, or combination products if they are intended to diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent a disease or condition, or to affect the structure or function of the body.2 The agency has long considered “any relevant source of evidence” to establish intended use, such as evidence of how the product is marketed.3 Medical products that are intended for an unapproved or uncleared new use—colloquially referred to as an “off-label” use—violate the FDCA, and are in FDA’s view “misbranded”4 as a matter of law.

In recent years, industry victories in cases such as Caronia and Amarin have escalated historic tensions between FDA’s off-label policy and the First Amendment. In June 2014, in the wake of the decision in Caronia, FDA responded to two citizen petitions5 that asked for better alignment between FDA’s off-label policy and the First Amendment6 by promising additional guidance on the subject.7

In the fall of last year, with no sign of the promised guidance, FDA opened a docket and hosted a public hearing to obtain input related to its “comprehensive review” of regulations and policies for off-label communications.8 Then, just days before President Trump’s inauguration, FDA issued the Consistent Communications Guidance, along with another draft guidance on communications with payors and formulary committees9 and a memorandum addressing the First Amendment (Memorandum).10 The issuance of these documents followed FDA’s finalization of its revisions to the “intended use” regulations on January 9. (The effective date of those regulations has been delayed until March 19, 2018, due to controversy over the revisions).11

Viewed together, this series of pronouncements is best understood as FDA’s attempt to find common ground with industry on communications that present diminished risk to the public health without conceding its authority to strictly regulate the space. FDA’s Memorandum, along with the text of the revised “intended use” regulations, reaffirm and defend the agency’s long-standing off-label policy on First Amendment grounds. The guidances, on the other hand—including the Consistent Communications Guidance that this article explores—effectively bless certain communications that previously may have been viewed as risky.

Overview of the Draft Guidance

The Consistent Communications Guidance provides that FDA will exercise enforcement discretion over manufacturer communication of information that: (1) is not contained in the FDA-required labeling, but (2) is consistent with the FDA-required labeling. In doing so, the draft guidance distinguishes this type of “consistent communication” from “off-label” communications (i.e., communications that are not consistent with FDA-required labeling).

Previously, in the absence of clarity on the meaning of the term “off-label,” some in industry had theoretical questions as to whether: (1) “on-label” should refer only to information contained in FDA-required labeling; (2) “off-label” should refer only to information that suggests a new intended use for a product (e.g., use in a new disease state, patient population, or route of administration); and (3) “out-of-label” should refer to all other information about a product. Although FDA does not use these terms, the draft guidance, conceptually, reflects the agency’s view of the scope of permissible out-of-label communications.

According to FDA, a communication is a “consistent communication” if each of the three following factors is satisfied:

Factor 1 – Is the communication consistent with four key conditions of use in the labeling?

- Indication. What purpose does the communication suggest for the product, and does it relate to a different indication than approved by FDA?

- Patient population. Who does the communication suggest are appropriate patients for the product, and is that patient population outside the approved population in the labeling?

- Limitations and directions for handling/ use. How does the communication suggest that a product can be used, and does it conflict with the use limitations or directions for handling, preparing, or using the product in the labeling?

- Dosing/administration. How does the communication suggest that a product can be administered, and does it conflict with the dosage/usage regimen, route of administration, and/or strength set forth in the labeling?

Factor 2 – Does the communication increase the potential for harm to patients? Communications are consistent with the labeling if they do not alter the benefit-risk profile of the product in a way that may result in increased harm to health.

Factor 3 – Are the directions for use in the labeling still sufficient, in light of the communication, to facilitate the safe and effective use of the product?

To help illustrate these points, the draft guidance provides several examples of out-of-label information that could be consistent with FDA-required labeling, including:12

- Information based on a comparison of the safety or efficacy of a medical product for its approved or cleared indication to another medical product’s same approved or cleared indication;

- Information that provides additional context about the adverse reactions associated with the approved or cleared uses of the product;

- Information about the onset of action for an approved or cleared indication and dosing or use regimen;

- Information about the long-term safety and/or efficacy of products that are approved/cleared for chronic use;

- Information about the effects or use of a product in specific patient subgroups that are included in its approved/cleared patient population;

- Information concerning the effects of a product that comes directly from the patient (i.e., patient reported outcomes) when the product is used for its FDA-approved/cleared indication in its approved/cleared patient population (e.g., a firm’s communication provides information concerning patient compliance/adherence, or a firm’s communication provides information about patients’ perceptions of the product’s effect on their basic activities of daily living);

- Information concerning product convenience; and

- Information about the mechanism of action described in the label.

FDA’s decision to include examples, such as onset of action, mechanism of action, patient-reported outcomes, and comparative claims signals a departure from its historical approach.

The Consistent Communications Guidance also provides that all claims, even if consistent with the labeling, still must be truthful and non-misleading. To avoid being deemed false or misleading, the draft guidance requires that claims be adequately substantiated.13 That means, according to the draft guidance, that any data, studies, or analyses supporting a “consistent communication” “should be scientifically appropriate and statistically sound to support the representations

or suggestions made in the communication.14”

This is a new substantiation standard, one that departs from, and appears to be lower than, the “substantial evidence” standard for drugs that previously was required to support most out-of-label statements in advertising.15 The new standard is also different from the “valid scientific evidence” standard applicable to certain devices.16

The guidance concludes by explaining that even adequately substantiated “consistent communications” must still be “presented with appropriate context17” to avoid being considered false or misleading. For example, “consistent communications” should:

- Accurately represent study results, data, or other information that support the claim;

- Disclose material aspects of study design and methodology (e.g., type of study, study objectives, drug dosage/use regimens, controls used, patient population studied, and outcome measures);Disclose material limitations of data (e.g., factors that can affect interpretability and reliability of the data, such as limitations of the data sources). Such disclosures, however, may be insufficient to prevent a communication from being false or misleading if the limitations of the data are so significant that the data does not support the representation made;

- Disclose any unfavorable or inconsistent findings;

- Reference information from FDA-required labeling to help contextualize the communication; and

- Present contextual information clearly and conspicuously.

Putting the Guidance to Work for Your Organization

The Consistent Communications Guidance opens the door to new types of manufacturer communications. But new opportunities are often accompanied by new risks, and it will be important for organizations to distinguish what the guidance does from what it does not do.

The draft guidance does not address off-label communications at all—it addresses only out-of-label communications—and it may do little to prevent future First Amendment challenges to FDA’s off-label policy. The draft guidance effectively allows manufacturers to make promotional communications based on some information that falls outside FDA-required labeling, but not all such information. It also effectively allows manufacturers to venture—proactively—outside the labeling with less than “substantial evidence” (for drugs) in hand, but it does not meaningfully explain how much evidence is necessary to substantiate a “consistent communication.” And, finally, it reminds manufacturers that claims can be misleading if not adequately contextualized, but it does not —nor could it—establish a one-size-fits-all safe harbor for truthfulness.

Since there is no definitive framework for evaluating the truthfulness of “consistent communications,” or for evaluating whether a communication alters the benefit-risk profile of a product, reliance on the draft guidance comes with inherent risk. To harness the opportunities presented by the draft guidance, and still mitigate risk, companies should consider:

- Standardizing an analytical framework for the analysis for “consistent communications,” to ensure consistency of review company-wide, e.g., across review teams and brands;

- Assigning decision-making authority on “consistent communications” to staff with higher levels of seniority and expertise;

- Seeking advice from outside scientists and regulatory professionals to help determine whether a proposed “consistent communication” disturbs the benefit-risk profile of a drug and is a fair and balanced depiction of the evidence; and

- Documenting decision-making processes, to ensure that “consistent communications” made now are defensible later, if challenged.

Although the comment period on the Consistent Communications Guidance ended April 19, 2017, companies may suggest revisions to guidance documents at any time.18 Given the need for additional clarity, we would not be surprised if FDA reissues a revised draft guidance for comment in the future. Nevertheless, in the meantime, if thoughtfully operationalized, there is opportunity in the current draft for companies to explore new ways of communicating about medical products.

- Consistent Communications Guidance, (Jan. 2017), accessible at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM537130.pdf.

- See 21 U.S.C. § 321(g) and (h).

- 82 Fed. Reg. 2193, 2206 (Jan. 9, 2017).

- See 21 U.S.C. §§ 331(a), (k), 355(a), 352(f), 351(f)(1), 352(o), 360, 360c, and 360e.

- See Citizen Petition submitted from a coalition of pharmaceutical companies (July 5, 2011), Docket No. FDA-2011-P-0512]; Citizen Petition of the Medical Information Working Group (September 3, 2013), Docket No. FDA-2013-P-1079.

- Letter from Leslie Kux, Associate Commissioner for Policy, FDA, to counsel for the Medical Information Working Group (December 22, 2014), at 8, accessible at https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FDA-2011-P-0512-0009.

- See id.

- 81 Fed. Reg. 60299 (September 1, 2016).

- Drug and Device Manufacturer Communications With Payors, Formulary Committees, and Similar Entities – Questions and Answers, Draft Guidance (Jan. 2017), accessible at https://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/@fdagov-drugs-gen/documents/document/ucm537347.pdf.

- Memorandum, Public Health Interests and First Amendment Considerations Related to Manufacturer Communications Regarding Unapproved Uses of Approved or Cleared Medical Products, accessible at https://www.regulations.gov/docket?D=FDA-2016-N-1149.

- 82 Fed. Reg. 14319 (March 20, 2017).

- See Consistent Communications Guidance at 6–8.

- Id. at 8.

- Id.

- See, e.g., 21 C.F.R. § 202.1(e)(6), (7).

- See 21 U.S.C. § 360c(3)(B).

- Consistent Communications Guidance, at 8.

- 21 C.F.R. § 10.115(f)(4).

Update Magazine

July/August 2017