Intellectual Property for the Food and Drug Law Professional: The Product Development Process

by Lacy Kolo and Thomas Wolfe

If you are lucky, you have an in-house intellectual property (IP) attorney at your company that counsels employees on all types of IP matters, from patents to trademarks to trade secrets. Your IP attorney works intimately with your research and development team to help design a cutting edge product. You have the analysis, opinions, and information at hand to show your product is innovative and patentable. You never doubt ownership and use of the product because of agreements used persistently throughout your organization. You are confident that your product brand and trademarks have multinational appeal—and are protectable. The look and feel of your product and packaging stands out from the competition and touts high quality. Your company has well-established processes and people in place who are dedicated to monitoring the marketplace and regulatory filings, and to then working with IP attorneys to continually update your IP portfolio to edge out competitors.

This article is for the rest of us. Over the year, we will be presenting three articles covering the processes, issues, and tools an IP attorney uses through the development and launch of a product. These articles are not meant to replace the sound advice of your in-house IP counsel or the IP attorneys at your outside law firms. Instead, these articles are meant to help you spot IP issues as they arise in the design cycle. In this first article, we introduce the types of intellectual property and the activities the IP attorney accomplishes in each product development stage.

This article is for the rest of us. Over the year, we will be presenting three articles covering the processes, issues, and tools an IP attorney uses through the development and launch of a product. These articles are not meant to replace the sound advice of your in-house IP counsel or the IP attorneys at your outside law firms. Instead, these articles are meant to help you spot IP issues as they arise in the design cycle. In this first article, we introduce the types of intellectual property and the activities the IP attorney accomplishes in each product development stage.

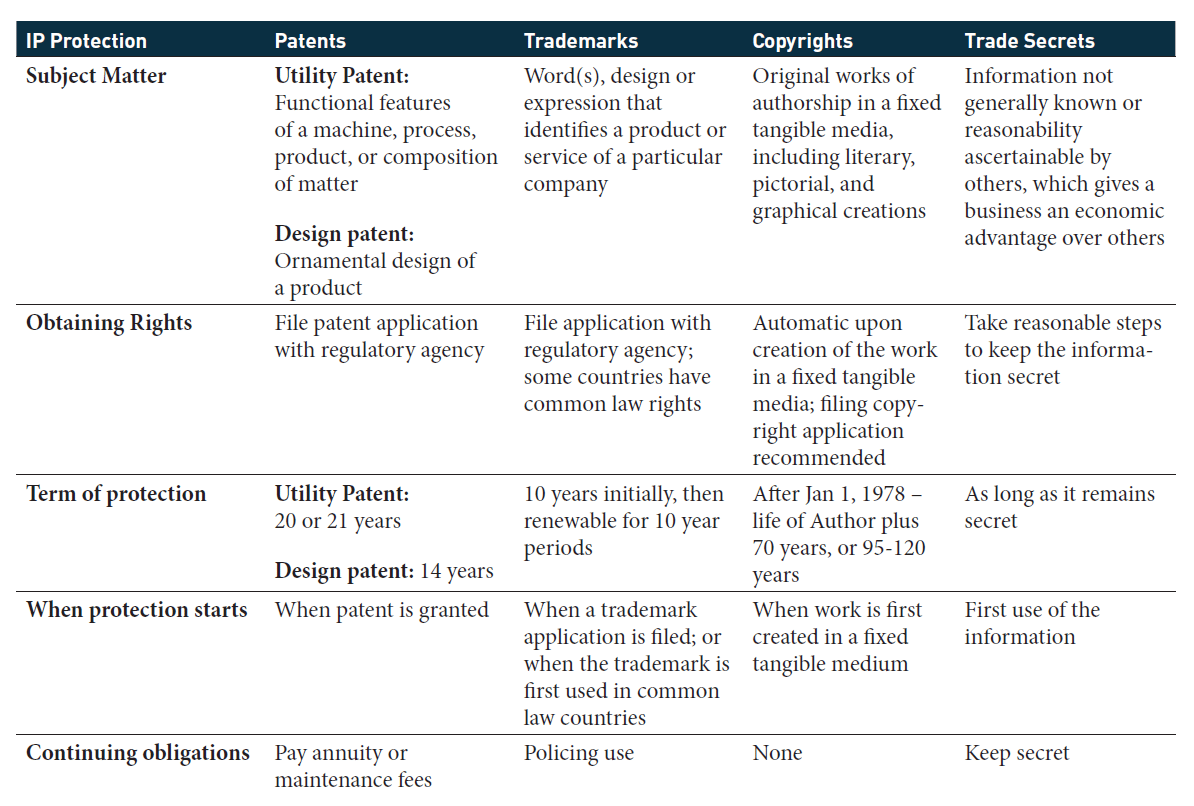

To understand how IP works with the product development cycle, first you must understand the four distinct types of intellectual property that may be generated during the development and launch of a product: patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets. Each type of IP varies in scope and term, as shown in Figure 1, and it is also subject to different common laws, state laws, and federal laws. For instance, patents and copyrights are the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal courts, but there are certain state laws for some aspects of the copyright “bundle of rights.”1 Trademarks are covered under both federal and state law. Trade secrets have traditionally been the purview of state courts; however, in 2016, the Federal Defend Trade Secrets Act gave federal scope to trade secrets.2

As such, IP covers a mélange of federal and state issues.

Types of Intellectual Property

Patents are awarded to inventors for novel, non-obvious, and useful inventions. Utility patents tend to cover functional features, and design patents cover ornamental features. A patent grants the owner an exclusive right to exclude others from practicing the claimed invention for a limited time.3 The process for obtaining a patent begins by filing a patent application in the jurisdiction’s regulatory agency that covers patents, in the United States this is the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). Back and forth argument between the inventors (generally through their counsel) and the PTO defines the scope of the issued patent, which is set forth in what are called claims. Patent laws have been harmonized among most countries by treaty, but even so each jurisdiction can each have slightly different patent laws. As such, the exact claims and scope of protection can vary by country. It is important to note that in the United States, the PTO can extend the term of a utility patent one of two ways—either through patent term adjustment (PTA), or through a patent term extension (PTE).4 PTA awards day-for-day credits to the normal patent term based on delays in prosecution by the PTO. PTE awards credits to the normal patent term to compensate the patent holder for patent term lost during the clinical development of their product and waiting for FDA approval. PTE rules are controlled by the Hatch Waxman Act, which limits PTE awards to patents for human drugs, food or color additives, medical devices, animal drugs, and veterinary biological products.5 The patent can be extended up to five years, provided that certain conditions are met.6

Trademarks protect consumers by identifying the source of a good or service. Trademarks can be words, expressions, symbols, fanciful designs, sounds, and smells. Under common law, trademarks should be marked by the TM mark when the good is placed in commerce. Under federal and state statutes, trademarks are registered in the jurisdiction and placed on a registry, and the ®designation may be used when the trademark is allowed. Like with patents, registering the trademark involves a back and forth negotiation with the PTO to determine if the trademark used in association with the goods or services is distinct. Because trademarks are meant to protect the consumer, the trademark holder must maintain the quality of the trademark and the goods associated with the licensee’s use of the trademark.7 If the trademark holder fails to do so, they may unknowingly invalidate the trademark. For this reason, trademark licenses typically include language stating the trademark owner has rights to monitor and inspect both the trademark use and the quality of the goods associated with the trademark.

Copyrights protect an original work of expression fixed in tangible form. The US Constitution grants this exclusive right in the section of the Constitution that defines the same for patents.8 The rights associated with copyrights are commonly known as a bundle of rights that include the rights to perform, distribute, display, reproduce, or prepare derivative works of the original work. Licenses to these rights may be granted individually or bundled together based on the needs of the licensee and the desires of the grantor.

Trade secrets are business information that gives an entity a competitive advantage over its competitors or customers. The scope of the types of information is broad and can include formulas, processes, customer lists, and commercial methods. Most issues related to trade secrets involves testing the processes used to secure the trade secret, e.g., whether you are properly controlling access to the trade secret, and ownership of trade secrets through agreement work.

Product Development Stages

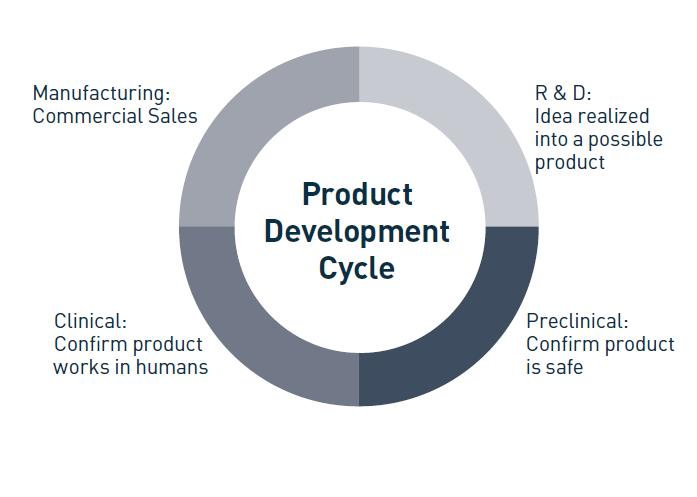

The product stages generally are consistent between all products, whether the product is new, a line extension, or an upgrade, although the length of each stage may vary. Figure 2 sets out the broad product development stages, which are research and development (R&D), pre-clinical, clinical, manufacturing, and commercialization. It is not atypical for one in-house IP counsel to be responsible for the IP work during all development cycle stages. Note, however, that when a law firm is providing the IP services, the IP team may change during the product development stages as specialists work on different aspects of the IP work.

i. R&D Stage

Like the name suggests, the R&D stage starts with developing an idea for a product, and then conducting the research necessary to develop a final article. At this stage, patents and trade secrets should be considered as the primary sources of IP protection. In a way, patents and trade secrets are counter to each other. A trade secret grants the owner rights but only as long as the trade secret is not publicly disclosed. Instead, the invention loses its trade secret protection if it is publicly disclosed. For patents, on the other hand, the invention owner obtains a limited monopoly in the marketplace for their invention in exchange for their disclosing the invention to the public. For this reason, it is not uncommon for a company to protect the product in the R&D stage as a trade secret until the company decides whether to pursue patent protection. It is recommended to only allow necessary individuals to access the trade secret, and to set procedures to monitor that access.

In the R&D stage, the IP attorney generally works with the engineers and contractors to determine what aspects of the final article are superior to other marketplace products and will give the company a competitive edge. The R&D stage is also the time to conduct patent landscape searches and develop agreements with co-developers. A patent landscape is a search of others’ patents and patent applications relating to the new product. The team can then use the search results to identify the product features that are new and novel and that should be protected as trade secrets or with patent filings. At this time, the team should also determine the members who contributed to developing those innovative features: these contributors are likely inventors.

Landscape searches can also flag potential infringement issues—if the product appears to be closely related to several patents, then the IP attorney may need to conduct a separate search called a “freedom to operate” search, which is discussed below in the pre-clinical stage section. The outcome of the freedom to operate can help the company decide where the company should devote resources to avoid infringing others’ intellectual property.

If there is more than one party working to develop the product, then typically the co-developers enter into agreements to define ownership of the IP before the product development begins. IP ownership rights are often balanced against the risks undertaken by the parties as well as their expected payoffs to find a mutually agreeable solution. In some co-developers agreements, ownership of the IP may be decided by first examining who is the inventor of the IP. Given that the product has not yet been developed, the product itself may still be hard to define at the agreement negotiation stage, which can lead to difficulties in project scope.

For at least these reasons, an IP attorney should be engaged in the project at the R&D stage to help define and protect the ownership rights of the product and to develop strategies to protect the early stage product, whether through patent filings or trade secret designations.

ii. Preclinical Stage

During the pre-clinical stage, the researchers answer basic questions about the product safety. Once the product is finally developed, i.e., after the R&D stage, is often when patent applications are initially filed. Thanks to the international Patent Cooperation Treaty, companies can initially file a patent application in their country of choice, and wait 30-31 months before deciding to pursue a patent in other jurisdictions. Patent applications can be filed for methods, devices, and systems that are new, novel, and non-obvious.

The preclinical stage is a time to broadly define the scope of the patents while providing as many specific embodiments as practicable. In this step, the engineering, marketing, and regulatory affairs professionals work with IP counsel to identify the portions of the product that have economic value. Each portion is a potential patent application, or at the very least, a portion of a patent application. By capturing both the breadth of the technology and the more nuanced specific aspects of the product that are valuable, the company ends up with a stronger patent portfolio that better protects the product value.

During the preclinical phase, a major undertaking of the IP attorney will likely be a freedom to operate. As the name suggests, the freedom to operate seeks to clear the product so that the launch of the product would be less susceptible to a claim of a third party that the product infringes another’s intellectual property rights. To conduct a freedom to operate, an IP attorney compares the new product to the claims of other patents that cover similar technology. The object is to see whether the product may be close to, and possibly infringe, another patent. The IP attorney either forms an opinion that the new product does not infringe the other patent, forms an opinion that the patent is invalid, i.e., that the new product cannot infringe the patent because it is not a valid patent, or the attorney may otherwise seek to obtain a license or purchase the patent in question. A freedom to operate at the pre-clinical stage is also critical to design concerns before larger investments in clinical stage design and manufacturing begins.

iii. Clinical Stage

It is common for the IP attorney to begin branding the product in the clinical stage. Here, the attorney works with the marketing team to create trademarks, i.e., names, logos, and phrases, that will be used when marketing and selling the product. This is also the time the attorney may conduct a trademark clearance, which is an analysis that compares the possible trademarks to other registered or unregistered trademarks used in the same field, to find if the possible trademark is distinct. Trademarks that are fanciful or otherwise non-descriptive are stronger and more protectable than common or otherwise descriptive terms. At the same time, the patenting process continues to proceed and the decisions are made about filings in other countries. If new, unexpectedly valuable features of the product are discovered, then additional patent filings may be filed as part of the initial patent family, possibly claiming the same priority date as that earlier filing.

Another concern to address at this time is the possibility that a competitor will design around any patents filed on the new product. As they say, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. If a new product sells well, competitors may try to find way to make a similar or identical product themselves in a manner that does not infringe the company patents. The team members and the IP attorney will therefore discuss how the product can be changed, and then possibly pursue additional patent filings to extend patent protection to adjacent technologies. Regulatory affairs professionals may help identify the unique aspects of the product that allow the product to succeed in regulatory filings so that the focus of the design arounds may lead to more valuable patent properties.

Finally, companies should be sensitive to the deadline to apply for PTE on their patents, if applicable. An application for PTE must be filed within sixty days of FDA approval of the product, even if the product cannot be commercially marketed at that time. For example, if the drug product is a controlled substance and cannot be commercially marketed due to domestic drug scheduling activities, the approval date for PTE purpose is the FDA approval date.

iv. Manufacturing Stage

The manufacturing stage is often when IP protection is developed to cover the look and feel of the product through trademarks, design patents, or trade dress. Packaging may also be protected through trade dress protection. Manufacturing agreements may also be used to protect the trade secrets that must be shared with manufacturers. To the extent that manufacturers may be responsible for the trademark, monitoring the quality of the manufacturer may be necessary. Other IP developed during this time includes user manuals and product manuals, which can be protected with copyrights. Because outside vendors may supply some aspects of these documents, the IP attorney may focus on the agreements in place with those vendors to verify that the manuals and other documents may be reproduced and disseminated lawfully with the products. It should also be noted that the process of manufacturing a product is in itself something that can be patented, which may be useful in particular for certain products, such as biologics.

v. Commercialization Stage

During the commercialization phase, the scope of protection in the patents, trademarks, trade secrets, and copyrights is finalized. The IP attorney may continue to file additional patent applications as competitors enter the market. Monitoring the marketplace is key for determining whether additional IP protection needs to be filed. Regulatory filings may be a good source to monitor, as early regulatory filings can alert the company to a competitor attempting to enter the same product space. During commercialization, the product may be marked with patents that cover the product. This may lead to increased damages from any infringer should a competitor launch a product that trespasses on the rights of the company.

Conclusion

The IP workflow described above may continue through multiple phases of the design process. Additionally, many of these processes can be recursive in nature as the product evolves over time. The higher the level of communication between the product team and the IP attorney, the more likely they should be able to identify issues early, before the issues prove costly. More communication may also result in a stronger position to launch a product, differentiating the innovative product from the competition.

In the next article in the series, we will move away from the timing of the intellectual property filings, and focus on the issues and problems that the IP attorney faces.

- 28 USC § 1338; see, e.g. Flo & Eddie Inc. v. Sirius XM Radio, No. 15-1164 (2d Cir. 2017) (Feb. 16, 2017).

- https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1890/text (last visited February 28, 2017).

- US Constitution, Art. 1 Sec. 8.

- PTO, Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, Chapter 2700; Sections 2701 and 2705.

- Originally known as the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (codified at 21 U.S.C. § 244(b), (j), (l); 35 U.S.C. §§ 156, 271, 282).

- Hatch Waxman generally provides that a patent may be extended for a period of up to five years, only the first approval of a new active ingredient qualifies for PTE, only one patent may be extended per new active ingredient, and PTE extends the term of only the new active ingredient and not the entire scope of the patent if directed to other embodiments. See, 35 U.S.C. § 156(a)(5)(A). The patent must be listed in the Orange Book.

- FreecycleSunnyvale v. The Freecycle Network, 626 E 3d 509 (9th Cir. 2010).

- US Constitution, Art. 1 Sec. 8.

Update Magazine

March/April 2017