Reality-Based Healthcare Reform

Introduction: Reality Isn’t Negotiable

When it comes to innovation in the development of new medicines, a key focus is on “Real World Evidence,”[1] or data based on what’s really happening in the real world (aka: reality). Unfortunately, as I’ve previously argued,[2] when it comes to healthcare policy, “real” seems to be conveniently ignored when it doesn’t suit the shibboleths of political agendas that prefer easy answers to complicated questions. As H. L. Mencken said, “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”[3] Case in point—the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and its call for government price controls for certain prescription medicines.[4]

Under the IRA, which was signed into law last August, Medicare will be able to negotiate certain prescription drug prices with pharmaceutical companies. This provision will initially apply to 10 drugs starting in 2026, and will expand to 20 drugs in 2029.[5] In practice, these “negotiations” are federally mandated price controls. Under the IRA, the government now has enormous power to name its own price for an increasing range of advanced medicines, and drugmakers will have little choice but to submit to such power.

The predictable outcome of price controls is the significant dis-incentivization of the research-and-development system that makes America the world leader in medical innovation. In the words of Philip Dick, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.”

Will Direct Federal Negotiations Lower Costs?

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Medicare Part D plans have “secured rebates somewhat larger than the average rebates observed in commercial health plans.” Additionally, the Medicare Trustees report that many brand-name prescription drugs carry substantial rebates, often as much as 20 to 30%, and on average, rebate levels have increased in each year of the program across all program spending.[6]

According to the CBO, revoking the Kennedy/Daschle Non-Interference Clause, would “have a negligible effect on federal spending” because CBO estimates that substantial savings will be obtained by the private plans and that the Secretary would not be able to negotiate prices that further reduce federal spending to a significant degree. Because they will be at substantial financial risk, private plans will have strong incentives to negotiate price discounts, both to control their own costs in providing the drug benefit and to attract enrollees with low premiums and cost-sharing requirements.[7]

The noninterference clause says: “[T]he Secretary: (1) may not interfere with the negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and [prescription drug plan] sponsors; and (2) may not require a particular formulary or institute a price structure for the reimbursement of covered Part D drugs.” According to the Senate Republican Policy Committee, “It leaves negotiations to insurers and other private businesses. Medicare Part D plans negotiate drug prices, determine which drugs are covered, and what patients will pay.”[8]

In 2007, after two years of experience with bids in the Part D program, CBO found that striking noninterference “would have a negligible effect on federal spending because . . . the Secretary would be unable to negotiate prices across the broad range of covered Part D drugs that are more favorable than those obtained by PDPs under current law.”[9]

In 2009, after even further program experience, CBO reiterated its previous views, stating that it “still believe[s] that granting the Secretary of HHS additional authority to negotiate for lower drug prices would have little, if any, effect on prices for the same reason that my predecessors have explained, which is that the private drug plans are already negotiating drug prices . . . .”[10] Importantly, CBO states that no further savings are possible unless the government restricts beneficiary access to medicines or establishes market-distorting price interventions.[11]

Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?

There are many issues and opinions regarding the benefits and risks of direct government negotiations of drug prices. But one key question remains . . . is the juice worth the squeeze? Is the imposition of price controls worth the benefit to society?

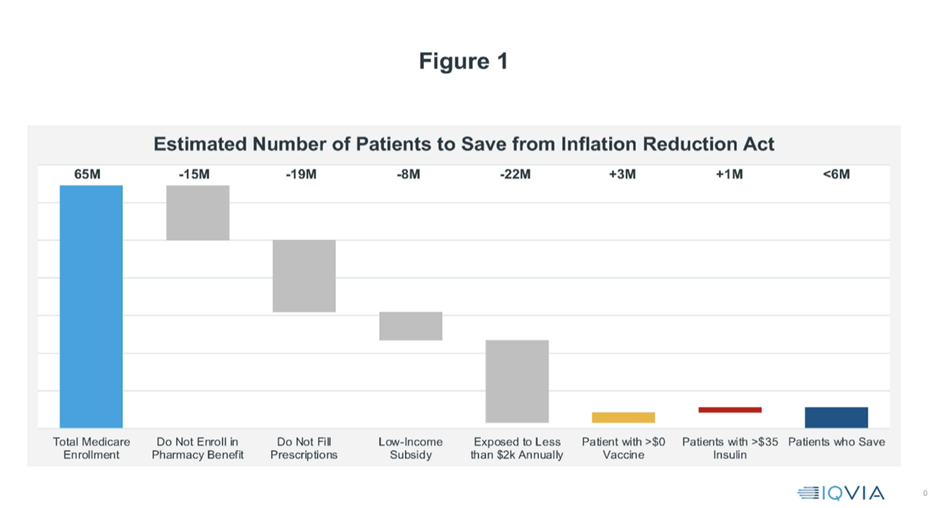

As Douglas Holtz-Eakin argues, while the IRA is advertised as substantially reducing drug costs for a wide swath of Medicare beneficiaries, under 6 million beneficiaries—less than 10%—will benefit at all (see Figure 1). For those who do benefit, savings are typically modest—69% of those with any saving will save less than $300.

The bottom line is striking. Of the 65 million Medicare beneficiaries, only 5.6 million are benefited by the IRA.[12] Is the juice worth the squeeze?

Price Controls Equal Choice Controls: Veterans Administration’s Experience

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) health insurance plan offers 1,300 drugs, compared with 4,300 available under Part D, prompting more than one-third of retired veterans to enroll in Medicare drug plans.[13] Patients vote with their feet. VA employs a narrow, exclusionary formulary to generate savings, and comparisons of coverage between VA and Medicare demonstrate that VA offers fewer choices, particularly of the most cutting-edge and innovative medicines. Of the top 200 Part D brand medicines, approximately 74% were covered by Medicare, compared to just 52% that could be covered by the VA formulary.[14] Similarly, the VA National Formulary[15] covers just 40% of first-in-class Part D medicines, compared to more than 62% in Medicare Part D.

According to the Government Accountability Office, “VA can steer utilization toward a limited number of drugs within a given therapeutic class. Medicare Part D plans, on the other hand, generally have broad networks of pharmacies and as such may have broader formularies than VA’s.”[16] Similar access restrictions are likely to appear in Medicare if Part D prices reference VA prices. A study from Columbia University found that just 19% of all new drugs approved since 2000 were covered by VA. And just 38% of drugs approved since 1990 were covered.[17] VA negotiating tactics are driving out some drug providers from the program, leaving patients with fewer treatment options.[18]

Developing medicines is already a risky business. It costs, on average, nearly $3 billion over 10 to 15 years for each approved new medicine.[19] That’s partly due to the direct expense of the research-and-development activity itself and partly because only 12% of potential medicines entering Phase I clinical trials ultimately win approval.[20] Private investors are willing to take such risks because a successful drug has the potential to earn back those costs—and then some.

During his 2022 State of the Union, President Biden claimed that under a price control regime, “Drug companies will still do very well.”[21] In fact, such a policy could reduce the revenue of the innovative biopharmaceutical industry by $1.5 trillion over the next decade.[22] These biopharmaceutical companies, on average, dedicate nearly one-fifth of revenue to research and development (R&D). Simple math suggests that price control legislation would cut funding for R&D spending by hundreds of billions of dollars.[23] Economic modeling estimates that price control legislation would snuff out 56 new drugs—including 16 cancer treatments—that would have otherwise reached patients.[24]

Where Do Drugs Come From?

There is a fundamental misunderstanding about the government’s role in drug development. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), for example, believes that pharmaceutical innovation is primarily driven by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the federal medical research organization.[25] But that has never been true.

A study by two Columbia University scholars in the journal Health Affairs uses historical data to reveal the real role NIH serves in drug development.[26] This study shows that fewer than 10% of drugs are covered by a public sector patent. And this slice of drugs only accounts for 2.5% of total annual drugs sales. Drugs that relied on federal funds for development, meanwhile, comprise only about a quarter of sales. The primary engine of drug innovation is private industry, which spends more than $50 billion annually on R&D.[27]

NIH focuses on basic research—that is, the study of fundamental aspects of organic phenomena without regard to specific medical applications. The biopharmaceutical industry, on the other hands, directs most of its R&D toward clinical research. Private science is centered on the actual development of new medicines. Both NIH and private firms provide research financing to academic institutions. But it is industry that employs most of the scientists that conduct the hands-on development work.[28] Drug development is a team effort and mustn’t be positioned by politicians, pundits, and agenda-driven advocates as an industry vs. government proposition.

Wither Innovation?

Government price controls will reduce the chances of an innovator’s opportunity to recoup a medicine’s development costs, which will plummet as a result, with the logical result being that new research will dry up. Everything from cancer breakthroughs to new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), COVID vaccines, and heart medications would become rarer. Those that did make it through the pipeline could be even more expensive, since, with fewer molecules in the pipeline, commercial competition will not act to reduce prices.

A recent review, led by University of Chicago economist Tomas Philipson, notes that studies consistently show that a 1% reduction in industry revenue leads to a 1.5% reduction in R&D activity. It finds that this legislation would reduce industry revenue by 12% through 2039 and R&D activity by 18.5%, or $663 billion. It also estimates that 135 fewer medications would be developed in that period as a result—a crippling shortfall that will also be measured in lives lost.[29]

Are Drugs too Expensive? Follow the Money

The list price of a medicine is meaningless to patients. When Americans with health insurance say that their drugs are “too expensive,” what they mean is that their copays and co-insurance rates are too high. Those rates aren’t set by pharmaceutical companies—but are the domain of the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and insurance companies. During the last few years, pharmaceutical spending has increased by 38%, while the average individual health insurance premium has increased by 107%.[30] During the same period, rebates, discounts, and fees paid by the biopharmaceutical industry to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers have risen from $74 billion to $166 billion.[31] That’s 37% of our nation’s entire expense on drugs.

Government policies should encourage rebate dollars to flow back to patients who need to take prescription drugs. Will greater transparency of contracting practices on the state level drive better pharmacy benefit manager behavior? That’s one theory. Such transparency efforts in New York and Connecticut, for example,[32] will be the bellwether. But greed often trumps shame and, without penalties, will PBMs choose to do the right thing by patients and reduce their hefty profits?

Pharmaceutical company rebates to pharmacy benefit managers that are tied to formulary restrictions create an incentive for entrenched market leaders to “bid” incremental rebates to prevent or limit access to competitive medicines. This model, coupled with escalating cost-sharing requirements, harms patients by driving up prices, resulting in reduced access to innovative drugs.

Allowing pharmacy benefit managers to continue with business-as-usual means a continued disincentive to promote a more aggressive uptake of both biosimilars and less-expensive generic drugs. Worse, reinforcing the status quo moves us even further away from a health care ecosystem based on competitive, predictable, free-market principles.

As I have argued elsewhere,[33] not following through on the proposed rule to ban rebates[34] is harmful to patient health and the public purse. One of the biggest threats to the body politic is nonadherence to the medicines physicians have prescribed: It causes 125,000 deaths each year[35] and is responsible for 10% of hospitalizations. Why don’t people take their medicines? Often because their copays and co-insurance rates are too high.

One of the troubling issues with the IRA is its continued lack of transparency. CMS has expressed an intent to bind drugmakers to confidentiality in price negotiations.[36] The American public will not see “the sausage” of how negotiated prices are determined, and confidentiality requirements will limit the extent to which the government can be held accountable for consistent and fair price determination decisions.

At the heart of the debate is whether we are going to improve our health care system using smart and evolving free-market principles, such as more focused regulation that addresses the exclusionary contracting that locks out savings from biosimilars, or go down the sound-bite-laden path of “free health care.”

Perverse Incentives Deny Patient Options

Per my argument in “The White House’s About-Face on Drug Rebates is a Loss for Public Health,” “Pharmaceutical company rebates to pharmacy benefit managers that are tied to formulary restrictions create an incentive for entrenched market leaders to ‘bid’ incremental rebates to prevent or limit access to competitive medicines. This model, coupled with escalating cost-sharing requirements, harms patients by driving up prices, which results in reducing access to innovative drugs.”[37]

FTC Weighs In

In June 2022, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted 5-0 to conduct a study of pharmacy benefits managers’ business practices.[38] FTC has since announced that the agency’s inquiry “will scrutinize the impact of vertically integrated pharmacy benefit managers on the access and affordability of prescription drugs.”[39] As part of this inquiry, FTC will send compulsory orders to CVS Caremark; Express Scripts, Inc.; OptumRx, Inc.; Humana Inc.; Prime Therapeutics LLC; and MedImpact Healthcare Systems, Inc.

The inquiry is aimed at shedding light on several practices that have drawn scrutiny in recent years, including[40]:

- fees and clawbacks charged to unaffiliated pharmacies,

- methods to steer patients towards pharmacy benefit manager-owned pharmacies,

- potentially unfair audits of independent pharmacies,

- complicated and opaque methods to determine pharmacy reimbursement,

- the prevalence of prior authorizations and other administrative restrictions,

- the use of specialty drug lists and surrounding specialty drug policies, and

- the impact of rebates and fees from drug manufacturers on formulary design and the costs of prescription drugs to payers and patients.

“Although many people have never heard of pharmacy benefit managers, these powerful middlemen have enormous influence over the U.S. prescription drug system,” says Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina M. Khan. “This study will shine a light on these companies’ practices and their impact on pharmacies, payers, doctors, and patients.”[41]

Sliding Down the Slippery Slope

The concept of federal “negotiations” on biopharmaceuticals is a slippery slope.[42] Yet, even as we’re debating the highly controversial implementation of the IRA, there’s already a cry that the IRA doesn’t go far enough. But those critics jumping on that manic toboggan are heading for a rude awakening, named “reality.”

According to the Orwellian-named “Strengthening Medicare and Reducing Taxpayer (SMART) Prices Act,”[43] (sponsored by Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), Peter Welch (D-VT), and 23 of their colleagues), “This legislation builds on Klobuchar and Welch’s provision included in the IRA that empowered Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices for the first time, unleashing the power of Medicare’s 50 million seniors to help lower drug prices for all Americans.” That’s quite an extraordinary statement considering, as Holtz-Eakin argues above,[44] that of the 65 million Medicare beneficiaries, only 5.6 million Medicare enrollees will benefit from the existing pricing codicils of the IRA. But with that kind of hyperbole, why stop there? The Klobuchar–Welch bill is a headlong dive down the slippery slope of even broader federal control of healthcare.

Consider this, the SMART Act calls for:

- creating a national formulary;

- increasing direct price controls for 20 drugs in 2026 (vs. the IRA’s current 10) and 40 drugs in 2027 (vs. 15-20 under the IRA);

- accelerating price controls for Part B drugs to 2027;

- ending the exclusion of drugs with generics/biosimilars since they won’t be on the market after three years. This is a considerably shorter time than small molecule data exclusivity under the IRA (5.5 years if awarded pediatric exclusivity); and

- changing the ceilings for the non-FAMP (Federal Average Manufacturer Price) formula prong of the MFP (Maximum Fair Price) from 75% to 76% for so-called “short monopoly drugs” and vaccines, from 65% to 55% for “extended monopoly drugs,” and from 40% to 30% for “long monopoly drugs.”

Note the nomenclature change. Rather than calling these healthcare technologies what they are—innovative and lifesaving—the authors of the bill view them as “monopolies.” Considering that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Commerce have announced efforts to pursue a whole-of-government approach to review its march-in authority, as laid out in the Bayh–Dole Act,[45] via an Interagency Working Group empowered to “develop a framework for implementation of the march-in provision that clearly articulates guiding criteria and processes for making determinations where different factors, including price, may be a consideration in agencies’ assessments,”[46] it’s fair to ask—is aggressive patent expropriation the next step in the process?

In 2019, the House of Representatives, under Speaker Nancy Pelosi, made the “Lower Costs Now Act” (the infamous H.R. 3)[47] their top legislative priority. It called for price controls via an international pricing index. Common sense prevailed and H.R. 3 was relegated to the ash heap of history. Today, before we can even fully understand the consequences (both intended and unintended) of the IRA, some members of Congress—this time in the U.S. Senate—are ready to take what they consider to be a Great Leap Forward in American healthcare reform. It is ill-considered and dangerous.

Sunshine is the Best Medicine: Reality-Based Legislation

In 2019, Senators Mike Braun (R-IN) and Mitt Romney (R-UT) introduced the “Prescription Drug Rebate Reform Act.”[48]

According to Senator Romney:

Patients in Utah and across the country are strapped with skyrocketing prescription drug costs, while insurance companies and drug manufacturers benefit from a complex system of rebates that results in higher drug costs. By changing the rules of cost-sharing, our bill aims to bring transparency to the prescription drug pricing system and lower out-of-pocket costs for medication.[49]

And, per Senator Braun:

The current system of government-sanctioned rebates for prescription drugs has distorted the drug pricing market. Drug prices—and out of pocket expenses paid by consumers—seem to continually be on the rise. What is not talked about enough, however, is the inherent conflict of interest arising from negotiated rebates that affect the actual cost of drugs, which are paid by drug makers to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in exchange for preferred status on insurers’ health plan formularies. This creates a perverse incentive for drug makers to continually increase drug list prices—at the expense of consumers. And even when drugs are covered by insurance—consumers with cost-sharing obligations are often required to pay 30 to 40 percent of high drug list prices out of their own pocket. These rebates are often hidden from consumers, contribute to high list prices for prescription drugs, and leave consumers with all, or a big part of the tab.[50]

Rethinking the Inflation Reduction Act

On June 6, 2023, Merck & Co. sued to halt the Medicare drug price negotiation program contained in the IRA. Merck’s position is that the IRA violates the Fifth and First Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, arguing that under the law, drugmakers would be forced to negotiate prices for drugs at below-market rates.[51]

Merck called the government’s tactics “coercive” and said it forces drugmakers to participate in “political Kabuki theater” by pretending negotiations are voluntary. “This is not ‘negotiation.’ It is tantamount to extortion,” Merck said in the suit. Merck also argues that the law will force companies to sign agreements conceding that the prices are fair, which it claims is a violation of the First Amendment’s protections of free speech.[52] Considering that the U.S. government is Merck’s biggest customer, this lawsuit takes guts.

Whether or not the Merck lawsuit is successful, the heart of the debate remains whether we are going to improve our health care system using smart and evolving free-market principles or go down the sound-bite-laden path of “government negotiation” (today) and “free health care” (tomorrow). IRA “implementation” is in the details—as is somebody else. As the late Admiral Hyman G. Rickover reminds us, “The Devil is in the details, but so is salvation.”[53]

Read CMPI’s Comments in regard to the initial implementation guidance for the Inflation Reduction Act’s “Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program” for initial price applicability year 2026.

[1] Real-World Evidence, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. (Feb. 5, 2023), https://www.fda.gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/real-world-evidence.

[2] Peter J. Pitts, Rejuvenating American Healthcare, 27 J. Com. Biotechnology 39 (May 2022), https://commercialbiotechnology.com/menuscript/index.php/jcb/article/view/1018/901.

[3] H. L. Mencken Quotes, BrainyQuote, https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/h_l_mencken_129796 (last accessed May 11, 2023).

[4] Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, H.R. 5376, 117th Cong. (2022), https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text.

[5] Juliette Cubanski, Tricia Neuman & Meredith Freed, Explaining the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act, KFF (Jan. 4, 2023), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/.

[6] Natalie McCormick, Zachary S. Wallace, Chana A. Sacks, John Hsu & Hyon K. Choi, Decomposition Analysis of Spending and Price Trends for Biologic Antirheumatic Drugs in Medicare and Medicaid, 72 Arthritis & Rheumatology 234 (Feb. 2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6994362/.

[7] Peter Orszag to Senator Ron Wyden, Letter from Congressional Budget Office Director (Apr. 10, 2007), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/reports/drugpricenegotiation.pdf.

[8] Medicare Part D: The Noninterference Clause, U.S. Senate Republican Policy Committee (May 22, 2019),

https://www.rpc.senate.gov/policy-papers/medicare-part-d-the-noninterference-clause.

[9] Letter from Donald B. Marron to Representative John D. Dingell, Letter from Congressional Budget Office Acting Director (Jan. 10, 2007), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/110th-congress-2007-2008/costestimate/hr410.pdf; Jim Hahn, CRS Report for Congress—Federal Drug Price Negotiation: Implications for Medicare Part D, Cong. Rsch. Serv. (Jan. 5, 2007), https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc818415/.

[10] Remarks of CBO Director Dr. Douglas Elmendorf before the Senate Finance Committee (Feb. 25, 2009), https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/62182.pdf.

[11] Setting the Record Straight on Medicare Part D Non-Interference, Council on Aging (Aug. 22, 2016), https://www.help4seniors.org/wpcontent/uploads/Downloads/newsletters/Noninterference%20Myth%20Fact%20(updated%208-22-16)%20FINAL.pdf.

[12] Douglas Holtz-Eakin, The 10-Percent Solution: Who Gets IRA Drug Price Savings? (Mar. 21, 2023), https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-10-percent-solution-who-gets-ira-drug-price-savings/.

[13] Prescription Drugs: Department of Veterans Affairs Paid About Half as Much as Medicare Part D for Selected Drugs in 2017, U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off. (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-111.

[14] Potential Access Implications of a National Formulary in Part D, AmerisourceBergen: Xcenda (July 16, 2020), https://www.xcenda.com/insights/comparing-the-generosity-of-drug-coverage-in-the-medicare-part-d-and-veterans-affairs-programs.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Prescription Drugs, supra note 13.

[17] Peter J. Pitts, Keep the Feds out of Drug Pricing, USA Today (Dec. 18, 2016), https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2016/12/18/keep-feds-drug-pricing-second-look/95490280/.

[18] Pitts, Rejuvenating American Healthcare, supra note 2.

[19] Olivier J. Wouters, Martin McKee & Jeroen Luyten, Estimated Research and Development Investment Needed to Bring a New Medicine to Market, 2009–2018, 323 JAMA 844 (Mar. 3, 2020), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762311.

[20] Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry, Cong. Budget Off. (Apr. 2021), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57126.

[21] Remarks of President Joe Biden – State of the Union Address as Prepared for Delivery, The White House (Mar. 1, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/03/01/remarks-of-president-joe-biden-state-of-the-union-address-as-delivered/.

[22] Kylie Stengel, Mitchell Cole & Kelly Brantley, Impact of H.R.3 as Passed by the House on Federal Spending and Drug Manufacturer Revenues, Avalere Health (June 19, 2022), https://avalere.com/insights/impact-of-h-r-3-scenarios-on-federal-spending-and-drug-manufacturer-revenues.

[23] Craig B. Bleifer & Caitlin E. Olwell, The Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 on Pharmaceutical Innovation, Patent Litigation and Market Entry, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP (Oct. 11, 2022), https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/alerts/the-impact-of-the-inflation-reduction-act-of-2022-on-pharmaceutical-innovation-patent-litigation-and-market-entry.

[24] International Reference Pricing Under H.R.3 Would Devastate the Emerging Biotechnology Sector, leading to 56 Fewer New Medicines Coming to Market Over 10 Years, Vital Transformation, https://vitaltransformation.com/2019/11/international-reference-pricing-under-h-r-3-would-devastate-the-emerging-biotechnology-sector-leading-to-56-fewer-new-medicines-coming-to-market-over-10-years/

(last accessed May 11, 2023).

[25] Sam Baker & National Journal, Elizabeth Warren vs. Big Pharma, The Atlantic (Jan. 22, 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/01/elizabeth-warren-vs-big-pharma/440358/.

[26] Francis K. Amankwah, Alexandra Andrada, Sharyl J. Nass & Theresa Wizemann, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Role of NIH in Drug Development Innovation and Its Impact on Patient Access: Proceedings of a Workshop (2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553542/.

[27] Brian Buntz, Pharma’s Top 20 R&D Spenders in 2021, Drug Discovery & Development (Mar. 30, 2022), https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/pharmas-top-20-rd-spenders-in-2021/.

[28] Amankwah, et al., supra note 26.

[29] Tomas J. Philipson & Troy Durie, The Evidence Base on The Impact of Price Controls on Medical Innovation, (Becker Friedman Inst. for Econ. at U. of Chic., Working Paper No. 2021-108, Sept. 14, 2021), https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/BFI_WP_2021-108.pdf.

[30] Role of Rebates in Cutting Drug Costs, Nat’l Council of State Legislators (Dec. 21, 2022), https://ncsl-podcasts.simplecast.com/episodes/role-of-rebates-in-cutting-drug-costs-oas-episode-176/transcript.

[31] Joseph R. Antos & James C. Capretta, Assessing the Effects of a Rebate Rollback on Drug Prices and Spending, Health Affs.: Blog (Mar. 11, 2019), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190308.594251/full/.

[32] Janet Kaminski Leduc, Pharmacy Benefit Manager Oversight Laws in New York and Other States, State of Connecticut Off. of Legis. Rsch. (Feb. 4, 2022), https://www.cga.ct.gov/2022/rpt/pdf/2022-R-0029.pdf.

[33] Peter J. Pitts, The White House’s About-Face on Drug Rebates is a Loss for Public Health, STAT News (July 11, 2019), https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/11/drug-rebates-white-house-decision/.

[34] Press Release, Trump Administration Proposes to Lower Drug Costs by Targeting Backdoor Rebates and Encouraging Direct Discounts to Patients, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. (Jan. 31, 2019), https://public3.pagefreezer.com/browse/HHS.gov/31-12-2020T08:51/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2019/01/31/trump-administration-proposes-to-lower-drug-costs-by-targeting-backdoor-rebates-and-encouraging-direct-discounts-to-patients.html.

[35] Meera Viswanathan, Carol E. Golin, Christine D. Jones, Mahima Ashok, Susan J. Blalock, Roberta C.M. Wines, Emmanuel J.L. Coker-Schwimmer, David L. Rosen, Priyanka Sista & Kathleen N. Lohr, Interventions to Improve Adherence to Self-Administered Medications for Chronic Diseases in the United States, Annals of Internal Med. (Dec. 4, 2012), https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00538.

[36] Meena Seshamani, Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program: Initial Memorandum, Implementation of Sections 1191 – 1198 of the Social Security Act for Initial Price Applicability Year 2026, and Solicitation of Comments, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs. (Mar. 15, 2023), https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-drug-price-negotiation-program-initial-guidance.pdf.

[37] Pitts, The White House’s About-Face, supra note 33.

[38] Press Release, FTC Launches Inquiry into Prescription Drug Middlemen Industry, Fed. Trade Comm’n (June 7, 2022), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/06/ftc-launches-inquiry-prescription-drug-middlemen-industry.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Karen Van Nuys, Geoffrey Joyce, Rocio Ribero & Dana Goldman, Overpaying for Prescription Drugs: The Copay Clawback Phenomenon, Leonard D. Schaeffer Ctr. for Health Policy & Econ., U. of S. Cal. (Mar. 12, 2018), https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/overpaying-for-prescription-drugs/.

[41] Press Release, FTC Launches Inquiry, supra note 38.

[42] Peter J. Pitts, The Inflation Reduction Act: Reality Isn’t Negotiable, RealClearHealth (Feb. 20, 2023), https://www.realclearhealth.com/2023/02/20/the_inflation_reduction_act_reality_isnrsquot_negotiable_285358.html.

[43] Press Release, Klobuchar, Welch, Colleagues Introduce Legislation to Boost Medicare Prescription Drug Price Negotiation, Lower Costs for Americans, Off. of Senator Amy Klobuchar (Apr. 24, 2023), https://www.klobuchar.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/news-releases?ID=0520D560-3366-4510-A757-AF6347B4D0DE.

[44] Holtz-Eakin, supra note 12.

[45] The Bayh-Dole Act: A Guide to the Law and Implementing Regulations, Council on Gov’t Rels. (Oct. 15, 2021), https://www.cogr.edu/sites/default/files/COGR%20Bayh%20Dole%20V.2.pdf.

[46] Press Release, HHS and DOC Announce Plan to Review March-In Authority, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. (Mar. 21, 2023), https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/03/21/hhs-doc-announce-plan-review-march-in-authority.html.

[47] Financial Impact of H.R. 3, “Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019”, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs. (Dec. 1, 2021), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/HR3.

[48] Press Release, Romney, Braun Introduce Legislation to Ensure Drug Pricing Transparency, Off. of Senator Mitt Romney (May 9, 2019), https://www.romney.senate.gov/romney-braun-introduce-legislation-ensure-drug-pricing-transparency/.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Michael Erman, Merck Sues US Government to Halt Medicare Drug Price Negotiation, Reuters (June 6, 2023), https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/merck-sues-us-government-halt-medicare-drug-price-negotiation-2023-06-06/.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Hyman George Rickover, Quotes of Famous People (Sept. 14, 2021), https://quotepark.com/quotes/1862505-hyman-george-rickover-the-devil-is-in-the-details-but-so-is-salvation/.

Update Magazine

Fall 2023

PETER J. PITTS, a former FDA Associate Commissioner, is President of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, visiting professor at the University of Paris School of Medicine, and visiting scholar at the New York University School of Medicine, Division of Medical Ethics.

PETER J. PITTS, a former FDA Associate Commissioner, is President of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest, visiting professor at the University of Paris School of Medicine, and visiting scholar at the New York University School of Medicine, Division of Medical Ethics.