Adoption Patterns of the FDA Food Code Across U.S. States

By Sharon Elhadad & Udi Sommer

Introduction

The Food Code is a series of guidelines published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that provides local, state, tribal, and federal regulators with a framework for the regulation of the food service and retail food industries (e.g., grocery stores and restaurants). The guidelines expand on the most effective ways to prevent foodborne illness and are in line with updated scientific findings as well as legal regulations. The guidelines are non-mandatory, and it is therefore up to the various relevant regulatory agencies to decide whether to adopt the Food Code in their jurisdictions.

The Food Code was updated on a biannual basis from 1993 to 2001; from that point onwards, it was updated every four years. The first edition to be published on the new interval was the 2005 Food Code, and the most recent full edition is the 2017 Food Code (the publication schedule was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the next scheduled complete edition of the Food Code is expected to be published in 2022).[1]

The stringency of Food Code revisions generally increases as the result of novel scientific findings in the four years preceding its publication.[2] Some claim that a significant limitation of the Food Code is that it contains a large amount of information that is not always easy to read and follow.[3] Nevertheless, FDA invests substantial efforts in creating educational programs to assist state and local agencies in interpreting and adhering to the provisions of the Food Code.

The Food Code is developed by a federal agency, but at the state level, all state regulatory agencies have discretion over whether to adopt the Food Code, the version of the Food Code they would like to adopt, the adaptations they may want to make, and the extent to which the provisions of the code are partially or fully integrated into their food regulations. State agencies may enjoy numerous benefits from adopting Food Code regulations, ranging from cost savings related to inspections and food safety training costs to improving consumers’ understanding of food safety and creating a common language between regulators and the industry.[4]

The process of adopting a new version of the Food Code, or parts of it, is not executed through direct legislative action; rather, food control “jurisdictions” (e.g., state agencies) develop their sanitation standards for food service and retail establishments and rely on the Food Code as a model framework. State legislatures have established regulatory agencies to regulate the food industry. These agencies develop their sanitation standards for food service and retail establishments and decide whether to rely on the Food Code as a model framework; adopting a new version of the Food Code is, therefore, not executed through direct legislative action. That is, the Food Code is offered to state legislatures as a guiding framework to adopt or incorporate into state and local laws or regulations concerning food safety, with the ultimate goal of protecting the public’s health.

State and local regulators also use the Food Code as a way to align their food safety rules with national food regulatory policy. In this sense, the Food Code promotes adherence to a uniform system, thereby in effect playing a somewhat similar role to other national associations or organizations that promote a uniform system, such as the Retail Food Safety Regulatory Association Collaborative, the Association of Food and Drug Officials , the Conference for Food Protection, or the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

It is worth noting that states vary with respect to the bureaucratic structure of agencies with regulatory oversight over its retail and food service establishments. A state can grant regulatory oversight to multiple agencies, with each assigned to regulate—either individually or as a group—different segments of the retail food industry.[5] Therefore, the number of state agencies with policymaking discretion over the adoption of the Food Code can vary substantially across states. In total, for the 50 U.S. states, there are 64 state agencies with regulatory oversight over restaurants and retail food establishments (or both). The number of relevant state agencies in a state can vary from one to three. The variance between states in the number of agencies with regulatory oversight over the two sectors leads to different levels of bureaucratic complexity, which may be associated with varying speeds of Food Code adoption, as discussed below.

We conducted an analysis to examine the Food Code adoption patterns across states. We framed our analysis as an instance of policy diffusion occurring in a context characterized by periodic significant changes to a policy established by a federal authority (i.e., FDA) but adopted by state agencies. In our study, we observe significant variation in terms of the speed with which new versions of the Food Code are adopted by state agencies and the duration of different versions of the Food Code adhered to by those agencies.

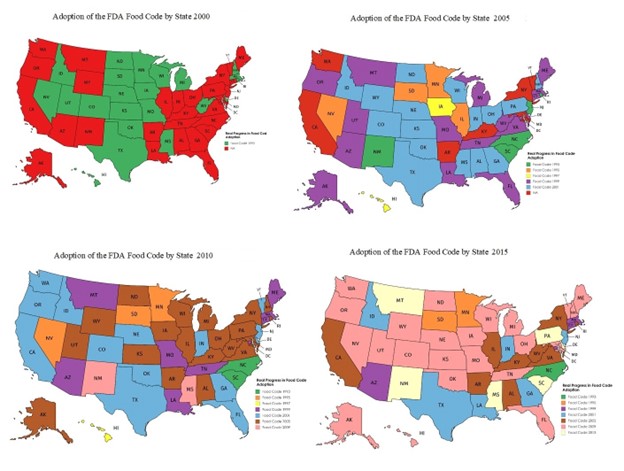

The maps in Figure 1 indicate that state regulatory agencies are generally inclined to upgrade their Food Code regulations over time, presumably to ensure more stringent food safety standards in their respective jurisdictions. That said, there is substantial variance between states, and the maps in Figure 1 also show some notable differences in Food Code adoption across states from 2000–2015 (in five-year intervals).

Figure 1. Adoption of the FDA Food Code by State, 2000–2015

Source: Real Progress in Food Code Adoptions report, covering the period 2000–2015, published by the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)

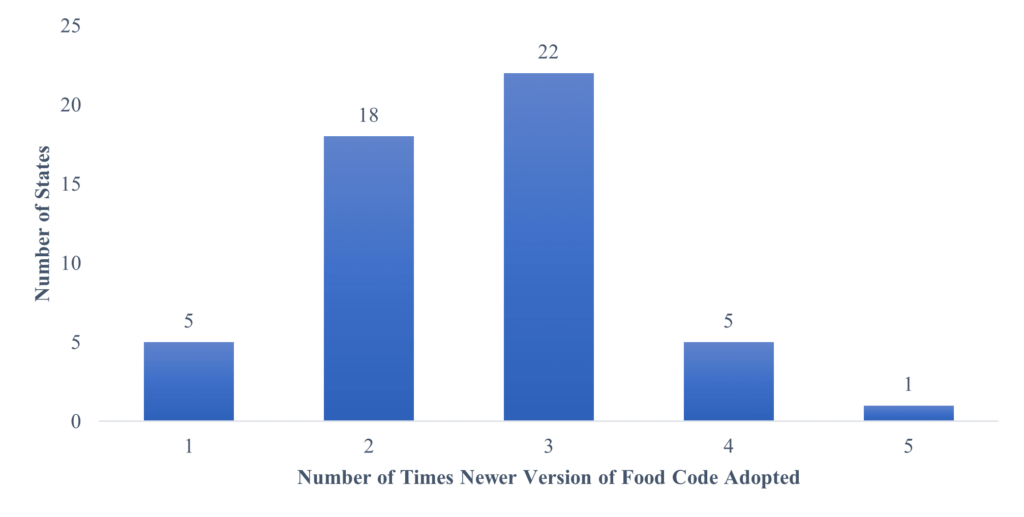

Figure 2 shows that between 2000–2016, each state adopted the Food Code at least once. Most states adopted a Food Code version two or three times during this period, and six states adopted a revised version of the Food Code either four or five times (Mississippi, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Utah). However, some states adopted a version of the Food Code only once (North Carolina, South Carolina, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C.).

Figure 2. Number of Times Newer Versions of the Food Code Were Adopted by States and Washington, D.C. (2000–2016)

Source: Real Progress in Food Code Adoptions report covering the period 2000–2016 published by the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)

To examine the potential reasons why states vary in the speed of adoption of different versions of the Food Code as well as the length of time during which a given version of the code remains in place in a state, we reviewed past research on policy diffusion to identify specific internal and external factors that may help shed light on the variation we observed. Traditional policy diffusion models rely on one-shot, binary frameworks, which, given the periodic nature of the Food Code publication process described above, render them less helpful for the purpose of examining Food Code adoption processes across sates. We, therefore, built a novel conceptual framework of policy diffusion that allows us to examine patterns of Food Code policy adoption across states in the context of periodically changing FDA regulations. Besides internal factors (e.g., state financial resources), we factored external factors (e.g., potential impact of federal government on policy adoption) into our analysis as well. This is important given that past studies in policy diffusion have indicated that states are influenced by the actions of both the federal government as well as other state governments.[6]

In our analysis, we factored in the political affiliation of relevant federal actors, including the U.S. President, the FDA Commissioner, the Senate, and the House of Representatives, as well as the political affiliation of relevant state actors such as state governors and state legislatures. We accounted for political affiliation given that past studies have produced ambiguous results regarding the potential impact of this variable on policy adoption.[7] In our analysis, we attempted to clarify the nature of the association between party affiliation at both the federal and state levels and policy adoption, at least insofar as it relates to food regulations.

In addition, we accounted for international factors like regulatory updates in European Union food policies as well as the number of global deaths from outbreaks of foodborne illnesses. Finally, we took into consideration internal state characteristics such as states’ annual revenue, the bureaucratic complexity of state regulatory agencies, the policy path dependency of the version of the Food Code in place in a state at a given time, and the level of professionalization of state legislatures (“professional” legislatures refer to legislative bodies where representatives serve as full-time employees and that meet frequently throughout the year; these stand in contrast to “citizen” legislatures, which generally meet far less frequently and where legislators may have other professional occupations).

Results

We found that the political affiliation of policymakers at both the state and federal levels of government may play an important role in the speed of policy diffusion, although the exact association between Democratic or Republican affiliation and speed of Food Code adoption is unclear. In addition, we found that several factors were related to a slower speed of policy adoption, including the number of global deaths from outbreaks of foodborne illnesses, the complexity of the bureaucratic structures of relevant state agencies, as well as policy. Our analysis also indicates that professionalized state legislatures were associated with faster Food Code adoption speed. Finally, we did not find evidence to support the notion that the Food Code adoption process is influenced by European Union regulatory policies or states’ annual revenue.

With respect to political affiliation, at the federal level, we found that a Democratic federal party index (a composite index we built to account for the political affiliation of the U.S. President, the FDA Commissioner, the Senate, and the House of Representatives) is associated with slower adoption of Food Code policy. Furthermore, our results also suggest that a Democratic state legislature is associated with a slower speed of Food Code adoption and longer policy duration. However, we also found evidence indicating that states with Republican governors were generally slower in adopting newer versions of the Food Code and were generally more inclined to maintain older versions of the Food Code in place for longer periods.

Given these results, we are reluctant to draw any firm conclusions regarding the relationship between party affiliation of relevant political actors and speed of Food Code adoption. This stands in contrast to the association between political party affiliation and individuals’ preferences for increased government action in the food realm,[8] in that more liberal individuals generally favored greater involvement by the public sector.

A higher number of global deaths from outbreaks of foodborne illnesses was associated with slower policy adoption speed. It appears to be the case that deaths from foodborne illnesses in other nations lead state agencies to “stick” with the current Food Code policies they are familiar with, perhaps in the belief that they will work effectively as tools to prevent future outbreaks of foodborne illnesses. Our study provides tentative results to suggest that the U.S. state agencies we examined were not influenced by non-domestic developments relating to food safety (this is in line with the finding on EU food regulatory updates).[9]

Furthermore, by evaluating various bureaucratic configurations by levels of complexity and by analyzing the association between this measure and policy adoption over time across different states, we assessed how bureaucratic elements potentially affect states’ speed of policy adoption. We found that greater bureaucratic complexity is associated with slower speed of policy adoption. This result supports the finding of previous researchers who found that multiple bureaucratic actors are negatively associated with policy diffusion[10] and adds to our understanding of policy adoption dynamics by emphasizing the importance of operationalizing measures of bureaucratic complexity.

In addition, we found that greater policy path dependency is generally associated with a slower average speed of policy adoption. That is, it may be the case that the FDA Food Code creates a self-reinforcing effect that generates “increasing returns” for the version of the Food Code currently in place, thereby favoring the status quo. For instance, states that adopt a new version of the Food Code generally need to expend significant effort, invest substantial time, and dedicate considerable resources to encouraging the implementation of updated policy provisions across the restaurants and food retail establishments in their jurisdictions. In a similar vein, there are sunk costs associated with the adoption of a given version of the Food Code (e.g., the resources already invested in informing, teaching, and monitoring the food service industry regarding the provisions of the current version of the code). These sunk costs also create incentives to preserve the current version of the code, making it more challenging for state agencies to adopt a newer version.

We also found that states with professionalized state legislatures are in general more proactive in adopting newer versions of the Food Code. This may be the result of legislators having more time to discuss the topic of food safety, which is generally not at the top of the agenda for most states; consequently, they may be more likely to influence relevant state regulatory agencies.

We also did not find evidence to suggest that state agencies were influenced by international institutions. That is, even though the EU is often considered in the industry to be an active promoter of best food safety practices, our analysis does not support the notion that traditional policy diffusion mechanisms, such as learning from relevant international actors or mimicking them, were significant factors underlying variance in Food Code adoption patterns.[11]

Finally, a state’s annual revenue was not found to be a relevant factor in explaining Food Code adoption patterns. This is interesting as we anticipated that richer states would be more inclined to adopt newer versions of the code.[12]

Conclusions

The adoption of food regulatory policies is a complex process shaped by several disparate regulatory and political factors. In our analysis, we obtained a number of interesting results. We found that bureaucratic complexity, the number of deaths from global outbreaks of foodborne illnesses, and policy path dependency were all associated with the slower adoption of newer versions of the Food Code. Additionally, we found that states with professionalized state legislatures are in general more inclined to adopt newer versions of the Food Code. However, we obtained mixed results regarding the relationship between party affiliation of relevant political actors at the federal and state levels and the speed of policy adoption.

As domestic markets become increasingly global and complex, so do the policies involved in governing them. Regulatory agencies responsible for the food industry may find it challenging to form a vision of food safety that forestalls future risks. With this in mind, analyzing the different factors that affect regulatory policy adoption in the food realm, including internal state characteristics as well as external federal- and state-level elements and international effects, can shed light on understanding the striking variance in the speed of Food Code adoption across states and the differences in the lengths of time various versions of the Food Code are in place. This study helps to further our understanding of the diffusion of food safety policies and may potentially help provide policymakers with concrete guidance to promote the more effective adoption of relevant regulatory pol

[1] As stated by FDA, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not possible to hold the required meetings; therefore, the next scheduled full edition of the FDA Food Code (10th edition) is planned for 2022 as opposed to 2021.

[2] André Schaffrin, Sebastian Sewerin & Sibylle Seubert. (2014). The Innovativeness of National Policy Portfolios–Climate Policy Change in Austria, Germany, and the UK. Environmental Politics, 23(5), 860–883.

[3] See, e.g., Certifying Board for Dietary Managers. 2021. Top Ten Things that CDM’s Should Know About the FDA Food Code. Retrieved October 26, 2022, https://www.cbdmonline.org/cdm-resources/cdm-cfpp-credential-code-of-ethics/fda-food-code.

[4] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020. Benefits Associated with Complete Adoption and Implementation of the FDA Food Code. Retrieved December 17, 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/96942/download.

[5] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020. Adoption of the FDA Food Code by State and Territorial Agencies Responsible for the Oversight of Restaurants and Retail Food Stores. Retrieved January 17, 2021, https://www.fda.gov/food/fda-food-code/adoption-fda-food-code-state-and-territorial-agencies-responsible-oversight-restaurants-and-retail.

[6] Dorothy Daley & James C. Garand. 2005. “Horizontal Diffusion, Vertical Diffusion, and Internal Pressure in State Environmental Policymaking, 1989–1998.” American Politics Research 33(5): 615–644.

[7] See, e.g., Robert L. Savage. (1985). “Diffusion Research Traditions and the Spread of Policy Innovations in a Federal System.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 15(4), 1–28.

[8] Jayson L. Lusk. (2012). “The Political Ideology of Food.” Food Policy, 37(5), 530–542.

[9] Fabrizio Gilardi. (2010). “Who Learns from What in Policy Diffusion Processes?” American Journal of Political Science, 54, 650–66.

[10] Srinivas Parinandi. (2013). “Conditional Bureaucratic Discretion and State Welfare Diffusion under AFDC.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 13(2), 244–261; Lael R. Keiser. (2010). “Understanding Street‐Level Bureaucrats’ Decision Making: Determining Eligibility in the Social Security Disability Program.” Public Administration Review, 70(2), 247–257; Zhang Qingmin. (2016). “Bureaucratic Politics and Chinese Foreign Policymaking.” The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 9(4), 435–458; Manuel P. Teodoro. (2009). “Bureaucratic Job Mobility and the Diffusion of Innovations.” American Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 175–189; Martin Lodge & Christopher Hood. (2003). “Competency and Bureaucracy: Diffusion, Application and Appropriate Response?” West European Politics, 26(3), 131–152.

[11] David Marsh & J.C. Sharman. (2009). “Policy Diffusion and Policy Transfer.” Policy Studies, 30(3), 269–288; Adam J. Newmark. (2002). “An Integrated Approach to Policy Transfer and Diffusion.” Review of Policy Research, 19(2), 151–178; Kurt Weyland. (2011). “Theories of Policy Diffusion Lessons from Latin American Pension Reform.” World Politics, 57(2), 262–295; Andrew Karch. (2012). “Vertical Diffusion and the Policy-Making Process: The Politics of Embryonic Stem Cell Research.” Political Research Quarterly, 65(1), 48–61.

[12] Everett M. Rogers. (2010). “Diffusion of Innovations, 4th Edition.” Simon and Schuster.

Update Magazine

Winter 2022

SHARON ELHADAD is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the Tel Aviv University School of Political Science, International Relations and Government. Elhadad holds an MA in Political Science (Magna Cum Laude) and an MA in Economics, with current research focusing on building a novel theoretical framework to analyze the policy diffusion dynamics of public health regulations in different contexts.

SHARON ELHADAD is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the Tel Aviv University School of Political Science, International Relations and Government. Elhadad holds an MA in Political Science (Magna Cum Laude) and an MA in Economics, with current research focusing on building a novel theoretical framework to analyze the policy diffusion dynamics of public health regulations in different contexts. UDI SOMMER is professor of Political Science at Tel Aviv University and has been a member of the Global Young Academy since 2019, of the Scientific Council of the Blavatnik Interdisciplinary Cyber Research Center, and of the Center for the Study of the United States at Tel Aviv University with the Fulbright Program. Sommer was Chairperson of the Israel Young Academy from 2018-2019 and co-chaired the Israeli Cyber Forum at Columbia University, while teaching political science at Columbia from 2016-18.

UDI SOMMER is professor of Political Science at Tel Aviv University and has been a member of the Global Young Academy since 2019, of the Scientific Council of the Blavatnik Interdisciplinary Cyber Research Center, and of the Center for the Study of the United States at Tel Aviv University with the Fulbright Program. Sommer was Chairperson of the Israel Young Academy from 2018-2019 and co-chaired the Israeli Cyber Forum at Columbia University, while teaching political science at Columbia from 2016-18.