Fido Has it All Figured Out: Lessons Learned from Animal Supplements May be Useful to Those Seeking a Human CBD Supplement Pathway

By Elizabeth Butterworth Stutts

The focus of this article is CBD supplements, particularly CBD supplements marketed for use in companion animals. Unlike human dietary supplements, pet supplements are not covered by the Dietary Supplements Health Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA). In the absence of this regulatory framework, the pet supplement industry has taken a proactive approach to hemp, drafting and implementing its own criteria to ensure product quality and risk management. Lessons learned from this industry may be useful to those seeking a regulatory pathway for CBD human supplements.

2018 was an epic year in the history of hemp. The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018,[1] also known as the Farm Bill, defined hemp, for the first time, as cannabis having less than 0.3%[2] of the psychotropic compound tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). This differentiation changed hemp from a Schedule One drug under the Controlled Substances Act[3] to an agricultural commodity, making private production of the plant legal on a national level.[4] In June of that same year, FDA approved GW Pharma’s Epidiolex, which has the cannabis-derived Phyto cannabinoid, cannabidiol (CBD) isolate as its active ingredient.[5] CBD’s status as the active ingredient in an approved new drug made CBD’s inclusion in supplements and foods illegal.[6] This status change leaves no pathway available for existing CBD health products other than the drug approval process.[7] While FDA and lawmakers debate the solution to this CBD conundrum, the hemp industry has galloped ahead without so much as a backward glance, notwithstanding the potential legal and regulatory repercussions. Meanwhile, with the proverbial “barn door” ajar, consumer demand for CBD health products, both for humans and pets, has simply exploded.

The CBD Pet Product Market

Although scientific literature on CBD[8] is not fully developed, cannabis has been used medicinally by many cultures for thousands of years.[9] In this country, there is common anecdotal acceptance of health benefits from using CBD[10] for humans, despite the lack of sufficient data from controlled studies. Even the World Health Organization has weighed in on CBD, concluding there is “no evidence of public health-related problems associated with the use of pure CBD.”[11] With human CBD health products in such high demand, it is no surprise that consumers want the same types of products for their pets, even though there is no basis for a correlation between the few human studies available and CBD use in pets. In fact, there is even less scientific support for CBD’s efficacy in animals (consider that evidence must always be species-specific) than there exists for humans. Nonetheless, parallels between human and animal health claims are regularly drawn by marketers and consumers alike, and many consumers wrongly equate the ubiquity of these products with FDA approval. As a result, CBD has become a “household” word.

And speaking of households, according to the American Pet Products Association (APPA), 70% of U.S. households, or approximately 90.5 million families, own a pet.[12] As one of the “silver linings” of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly one in three Americans adopted a pet during the shutdown,[13] so the pet product industry, in general, is experiencing record growth. A study conducted by Grandview Research estimated the value of the global CBD companion animal market in 2019 at $27.7 million.[14] That study predicts a compound annual growth rate of 40.3% between 2020 and 2027.[15] Another recent study conducted by Brightfield Group estimates the companion animal CBD market will generate $629 million in sales in 2021 and $1.1 billion in 2025.[16]

An overwhelming number of CBD animal health products are purchased for dogs, but the purchases for cats rose from 17% in 2020 to an estimated 21% in 2021.[17] Purchases are also made to benefit rabbits, birds, fish, horses, and reptiles, but together these groups make up less than 3%.[18] According to the Brightfield Study, the typical buyer of any cannabis pet product is an urban (46%) Millennial (53%).[19] Suburban dwellers (30%) and Gen X (22%) are just trailing behind. Baby Boomers (14%) and Gen Z (11%) round out the mix, along with rural inhabitants (15%) and those living in small towns (9%).[20] The ratio of men to women is about even, with women making up 55% of the buyers and men, 45%.[21]

The proposed mode of action for CBD is based on limited research evaluating CBD’s effects on the endocannabinoid system.[22] With few exceptions, all animals (including man, but except insects) have some form of an endocannabinoid system. Even animals as simple as sea urchins and leeches have an endocannabinoid system.[23] Although scientists still have much to learn, the endocannabinoid system is a nerve signaling system believed to be a regulator of sorts that helps keep our bodies in harmony with our environment.[24] CBD, a cannabinoid, may enhance the natural effects of an animal’s own endocannabinoids.[25] It is believed there are two main types of endocannabinoid receptors, known as CB1 and CB2, which are distributed in various patterns throughout the body. This pattern is unique to each type of animal, so CBD’s action should vary among animals, depending on species, dose, and metabolic rate.[26] This is a difference that pet owners frequently fail to appreciate.

Dr. Patti Mayfield, a member of the Veterinary Cannabis Society and a hemp farmer based in Bend, Oregon, says the public perception of what-is-good-for-me-must-be-good-for-my-pet creates many problems. She says, “Dogs are not little humans in fur coats. They are different. And they have a far different way of responding to certain cannabinoids, especially THC.”[27] Next to humans, dogs are the animal species most studied in the world of CBD. Scientists have found that dogs have far more CB1 receptors in the cerebellum than humans,[28] and this difference makes dogs far more sensitive to THC than humans. In fact, THC not only does not make dogs “high,” it can make them, albeit temporarily, really sick.[29] Thus, it is perhaps even more important for dog CBD products to be devoid of THC content than for human products.

In contrast, initial CBD toxicity studies in dogs show that dogs treated with pure CBD appear to suffer few, if any, side effects, and those observed are only transient and mild.[30] The only exception is an occasional elevation of liver enzymes following treatment.[31] However, these studies are just preliminary.

The fact that the endocannabinoid system varies in structure and function from species to species helps illustrate the most obvious practical difference between the human and animal CBD health product industries. While we humans may have subtle variations in race, gender, age, and ethnicity, human products are all developed for one animal species, Homo sapiens. In contrast, animal products must be safe and effective for each species for which the product is proposed.

The Pet Supplement Industry’s Response to the CBD Regulatory Dilemma

Human and animal CBD supplements face the same major regulatory barrier to an approval pathway. Since CBD is the active ingredient in a new approved drug product (Epidiolex), under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act (FDCA), 21 U.S.C. Section 355, products containing that substance are excluded from the definition of a dietary supplement.[32]

The debate surrounding this issue has focused on the general expectation that FDA will craft an exception to exclude CBD from foods and supplements under the FDCA.[33] The Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) has the authority to make an exception to the exclusion under sections 201(ff)(3)(B)(i) and (ii) of the FDCA relevant to dietary supplements. Specifically, supplements containing active drug ingredients not in prior use are illegal “unless the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, has issued a regulation, after notice and comment, finding that the article would be lawful under this chapter.”[34] The other option, of course, is legislative. As of the writing of this article, Representatives Kurt Schraeder (D-CO) and Morgan Griffith (R-VA) are proponents of proposed legislation that would force FDA “to proceed with rulemaking on [CBD] by no later than 180 days after enactment.”[35]

A vast majority of the hemp-derived CBD products for humans currently on the market—of course, without FDA approval—can be described, at least in layman’s terms, as human dietary supplements and subject to DSHEA.[36] This law established dietary supplements as a separate category of food containing “dietary ingredients.” DSHEA defines “dietary ingredients” as a vitamin, mineral, herb or other botanical, amino acid, a dietary substance already used to supplement the diet by increasing total dietary intake, or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination of any of these aforementioned ingredients.[37]

However, this is the crucial point at which the approval pathways for human and animal supplements diverge. While DSHEA is front stage and center in any analysis regarding the legality of human CBD supplements, DSHEA is inapplicable to veterinary products. In its legislative history, Congress made explicitly clear its conscious intent to exclude veterinary products from DSHEA.[38] If there is no “DSHEA-for-pets,” how are pet supplements on the market? The short answer is this: the pet supplement industry is largely self-regulating and works cooperatively with FDA to ensure product quality and risk management.

The Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) is the division within FDA tasked with the approval and regulation of animal food,[39] drugs, and devices.[40] The scope of FDA/CVM’s authority over veterinary products is quite broad. Section 201(v) of the FDCA defines a “new animal drug” as “any drug intended for use for animals other than man, including any drug intended for the use in animal feed.” As in human products, when a new animal product is considered, the first inquiry is the proposed use of the product. If the product provides nutrition, then the product is a food.[41] This definition includes feed supplements delivering essential vitamins and minerals for which a nutritional value has been established. However, if the product is designed to deliver a substance, other than food, to support a specific structure/function of the body of a companion animal and, as in the case of CBD, glucosamine, or curcumin,[42] for example, there are no established nutritional guidelines for the substance, it is a Dosage Form Animal Health Product (DFAHP). Because there is no DSHEA-for-pets, all DFAHP’s are technically unapproved drugs. Although there is no formal guidance document memorializing CVM’s approach to DFAHPs, CVM uses its enforcement discretion regarding these low-risk products, so long as they are marketed for non-food producing animals (eliminating downstream effects on the food chain and human health) and no overt drug claims are made in labeling or promotion. This relatively harmonious relationship between FDA and the industry did not happen by chance. The pet supplement industry has worked cooperatively and transparently with FDA and state regulatory agencies since 2001 to establish this relationship.

For those who focus solely on human products regulated by FDA, it may come as a surprise to learn that the animal supplement market operates in this regulatory “gray zone.” To understand how this evolved, one must first appreciate the practical differences within FDA. While the regulatory structure on the “human side” is well-developed, the infrastructure for animal foods and supplements is much less so.[43] That is why two independent, non-profit, industry-specific organizations, the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) and the National Animal Supplements Council (NASC), support FDA and state agencies with regulation and oversight of animal foods and supplements, respectively.

An analysis of the animal supplement industry would not be complete without a brief discussion of the animal food ingredient regulatory process. FDA/CVM regulates animal foods under the Food Safety and Modernization Act of 2011 (FSMA)[44] but shares its regulatory responsibility with state governments. As a practical matter, the individual states are far more heavily involved in regulating the production and sale of animal food than FDA. AAFCO is a non-profit organization whose members are representatives from agencies representing the individual states, FDA/CVM, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. AAFCO works cooperatively with industry and regulators to consistently identify and define animal foods that are safe and nutritionally appropriate for animals. AAFCO maintains a comprehensive list of approved ingredients for animal food use in its database, found in the AAFCO Official Publication (AAFCO OP).[45] In addition, AAFCO OP contains model regulations for pet food and a checklist for labels. While AAFCO has no regulatory authority, it promotes interstate commerce by encouraging the harmonious regulation of animal foods among all 50 states.[46]

As to hemp and hemp-derived products, AAFCO’s official position is consistent with FDA’s position. No hemp or hemp products are currently allowed in animal or pet food in the United States. However, AAFCO encourages the industry to submit safety and nutritional information on hemp seed oil, hemp seed meal, and whole hemp seeds as possible animal food ingredients. Even though these hemp products are Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) for human consumption, GRAS approval for these products for humans does not extend GRAS approval for animal consumption.[47] (Think about chocolate, for example, which, while safe for humans, is toxic for dogs.) As to CBD products for animals, AAFCO says they “need to be treated as drugs because the intended uses are largely associated with drug claims.”[48]

Likewise, the NASC exists to support the companion animal supplement industry.[49] Like AAFCO, NASC is an industry-specific organization that cooperates with regulators to provide quality guidelines and systems of continuous vigilance (risk monitoring) for manufacturers and marketers of companion animal health supplements. But unlike AAFCO, NASC is composed of industry leaders, not regulators, and membership is voluntary. While NASC has no official authority to “regulate” the industry, membership in NASC is predicated on its members’ agreement to abide by NASC guidelines.

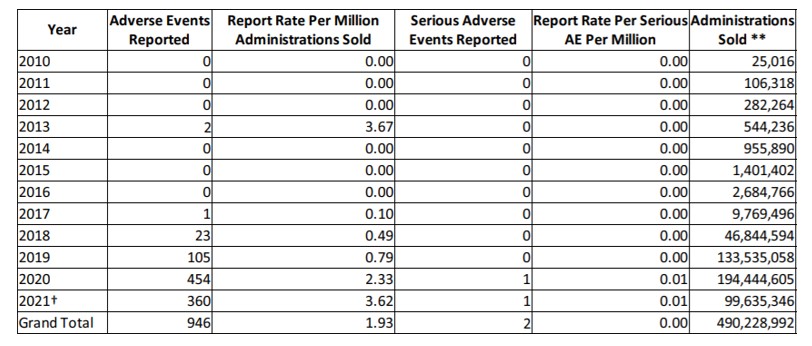

NASC has drafted and implemented model cGMPs and labeling guidelines for pet supplements, based largely upon FDA’s Small Entity Compliance Guide on Structure/Function Claims[50] and other similar agency material for human supplement manufacturers. Member applicants are reviewed to ensure compliance with NASC standards before membership in NASC is confirmed. NASC members must agree to uphold NASC specific standards in sourcing, manufacturing, packaging, labeling, and promoting animal supplements, according to NASC rules, which are modeled after DSHEA and FSMA. Members face monetary penalties or even expulsion for non-compliance with NASC standards. NASC requires member companies to conduct regular product audits and provide Certificates of Analysis (COAs), ensuring product quality and consistency. NASC also maintains a sophisticated database of adverse events[51] related to animal supplements called NAERS™, which stands for NASC Adverse Event Reporting System. The table, below, is an excerpt from NAERSTM, showing the virtual non-existence of adverse events for CBD products, reported through 8/6/2021.[52] In sum, NASC’s cumulative data on CBD indicates it has an excellent safety profile when used in animal supplements.

Bill Bookout, the President of NASC, explained how his organization came into being. In the years leading up to DSHEA, the animal supplement industry followed the human supplement industry, growing at an equally rapid pace, though on a much smaller scale. CVM became concerned that many of these unapproved drug products could jeopardize animal safety. Since animal supplements were unaffected by DSHEA, FDA/CVM decided to use its enforcement authority to rein in the rapidly proliferating DFAHP market.

In 1999, Bookout had started an animal supplement company and thus had personal “skin in the game.” He knew that most animal supplement companies—including his own—would not survive the regulatory crackdown. Rather than stand by and watch his company’s demise, along with many others in the nascent animal supplement industry, as an industry representative, he met with regulators at CVM to try and find a solution. Bookout, a businessman, though new to animal supplements, was experienced in the health product industry. He well understood the underlying mission of CVM was animal safety, not the bankruptcy of animal supplement companies such as his own. But CVM was in a bind. There was no established regulatory pathway for these products other than a full-scale investigational new drug application (INDA) that most, if not all, animal supplement companies could hardly afford to pursue.

So Bookout formed NASC, a non-profit, self-regulatory organization to promote safe, quality supplement products through transparent, collaborative action with CVM and state regulators. Then he asked CVM to consider consumer expectations and demand before taking enforcement action, as the pet supplement market was, by that time, in full swing. Regulatory enforcement would eliminate many products from the market, leaving consumer demand unmet. These consumers would likely procure “black market” supplements for their pets or substitute similar products developed for humans instead of animals. Either result would do nothing to promote animal safety. On this basis, Bookout convinced regulators that an industry crackdown was more likely to harm animals than to protect them. “The market demand was already there,” he said, “and it was not going away. If CVM had driven these companies out of the market, they would have forced animal owners to use less suitable products. In the end, assuming that animal health and safety is paramount, which it was, the best decision was to support these companies, not eliminate them.”[53] And with that understanding, Bookout and his company became the founding member of NASC and along with many other leaders in the industry, began the process of voluntary, self-regulation.[54]

Since that time, the NASC has grown to over 280 members that market animal supplement products. Only NASC members can use the NASC “seal” on a supplement label. The seal indicates the product has passed a comprehensive quality audit and helps ensure that labeling is accurate, and that product quality meets NASC’s high industry standards. Bookout proudly points out he is unaware of any FDA inspection of an NASC member manufacturer that has resulted in 483s or any other negative outcome.[55]

True to his modus operandi, Bookout has ensured that NASC is ahead of the regulatory curve regarding hemp and hemp-derived products. His organization has already implemented a policy entitled, “NASC Labeling & Testing Requirements for Members Marketing Products Containing Hemp or any Hemp Derivatives.”[56] The policy says that members must not use any confusing terms describing hemp products and gives examples of what labeling can and cannot say. Manufacturers of DFAHPs containing hemp must certify that any THC concentration is below 0.3%, must independently verify the CBD concentration stated in labeling, and certify that the product is free from microbes, pesticides, and heavy metals. Regular product testing and COAs are also required.[57]

In addition, to avoid the Epidiolex prohibition on CBD isolate, no synthetic or isolate CBD products are acceptable ingredients in NASC animal supplements. Only “broad spectrum” hemp (extract containing all compounds naturally found in hemp, with THC processed to be below 0.3%) or “full-spectrum” hemp (extract containing all compounds naturally found in hemp, where the cultivar’s THC levels are grown or diluted to be less than 0.3%) may be used in animal supplements. Importantly, all labeling and promotional claims must comply with FDCA Section 201(g)(1)(c) “for articles [other than food] intended to affect the structure of any function of the body of . . . animals.” Most important, no supplement can be labeled with drug claims or otherwise violate FDCA Section 201(g)(1)(b).

In the meantime, a brief internet search will yield many CBD animal supplements, chews, and treats made and marketed by non-NASC members. Many of these products make unapproved disease claims akin to those frequently made for human products. Examples include CBD “helps with inflammation and pain control” or “prevents dermatitis.” Additionally, independent tests of both human and animal CBD supplements continue to reveal wide discrepancies in the amount of CBD claimed in the labeling and the amount measured in the product sample.[58] Other CBD products have tested positive for non-disclosed amounts of THC and other impurities.[59] Of perhaps the most concern is the presence of heavy metals found in some CBD products. As cannabis is a well-known phytoremediator of soil, it readily absorbs heavy metals from the soil in which it is grown. (In fact, cannabis plants were used to remediate soil in Chernobyl.)[60] Thus, CBD products sourced from China, a country with some of the most contaminated soil globally, present a particular risk to consumers.[61]

If you ask Bookout about these products, he will tell you that most are made by companies with executives who simply do not know any better or, in some cases, act irresponsibly.[62] Those companies run the risk of FDA enforcement, investigations by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), or defending peer-submitted complaints to the National Advertising Division (NAD). State authorities may enforce state-specific rules relating to CBD products, as all 50 states regulate CBD to varying degrees. Companies that sell products inconsistent with state regulations may face any number of state-initiated enforcement actions or even class-action suits brought under consumer protection statutes.[63] In some states, like Florida, CBD-infused pet treats are “legal,” notwithstanding FDA, so long as certain conditions are met.[64] Other states, such as Idaho, have yet to recognize the legality of any cannabis product, including hemp.[65] This patchwork regulation makes it extremely difficult for manufacturers to comply with laws from state to state, and compliance is particularly difficult for smaller companies. In contrast to those companies operating outside of the auspices of NASC, the internal audits of NASC member companies prevent them from making similar mistakes. “We’ve been working on our internal hemp guidelines for quite some time. We did not want to wait for the legislature to craft a solution or for the lengthy administrative process through the FDA, which may or may not include animal products in the solution. Our goal was to have firm guidelines in place as quickly as possible. We are very proud to have achieved our goal.”[66] Bookout is also quick to point out, “without the help and input from the regulators, we would not have made the progress we have, which benefits everyone, especially the animals.” In sum, a proactive attitude and a genuine desire to cooperate with regulators have worked well for this industry.

While the rest of us wait for lawmakers and FDA to craft a pathway for human CBD supplements, at least consumers of NASC member products have some assurance of the quality and risk of the supplements they give to their pets. Perhaps the human CBD supplement industry should follow Fido’s lead.

The author would like to thank George Mason law student, Jacob Hopkins, for his assistance, and welcomes comments or questions. [email protected]

[1] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Development & Approval Process (updated Mar. 2, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process.

[2] THC is measured as a percentage of dry weight. A discussion of animal products using THC is beyond the scope of this article.

[3] Narcotic Addict Treatment Act of 1974 (Controlled Substances Act), 93 P.L. 281, 88 Stat. 124, 93 P.L. 281, 88 Stat. 124.

[4] The hemp industry is regulated under the joint auspices of the USDA and states’ departments of agriculture. U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Development & Approval Process (updated Mar. 2, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process.

[5] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., Statement on New Steps to Advance Agency’s Continued Evaluation of Potential Regulatory Pathways for Cannabis-Containing and Cannabis-Derived Products, FDA Press Announcements (April 2, 2019), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-new-steps-advance-agencys-continued-evaluation; GW Pharm., Home Page, https://www.gwpharm.com/ (last visited Aug. 4, 2021).

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] CBD is the second most prevalent Phyto cannabinoid in cannabis, next to tetrahydrocannabinol. Zerrin Atakan, Cannabis, A Complex Plant: Different Compounds and Different Effects on Individuals, 2 Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 241–54 (2012) (available at doi:10.1177/2045125312457586).

[9] Britannica ProCon.org, History of Marijuana as Medicine – 2900 BC to Present, https://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/historical-timeline/ (last visited Aug. 4, 2021).

[10] CBD is just one of the many chemical compounds found in hemp. Other non-THC cannabis-derived compounds are also being researched for potential health benefits. Unfortunately, space precludes inclusion of these other compounds in this article.

[11] World Health Organization, Cannabidiol (CBD) Pre-Review Report Agenda Item 5.2, Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, 9th ECDD (2017), https://www.who.int/medicines/access/controlled-substances/5.2_CBD.pdf.

[12] Am. Pet Products Assoc., APPA 2021-2022 National Pet Owners Survey, 4 https://americanpetproducts.org/Uploads/NPOS/NPOS21-22_TOC.pdf.

[13] See generally Insurance Rsch. Council, Consumer Responses to the Pandemic and Implications for Insurance (Oct. 2020), https://www.insurance-research.org/; Insurance Information Inst., Facts + Statistics: Pet Ownership and Insurance (2020), https://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/facts-statistics-pet-ownership-and-insurance.

[14] See Grand View Rsch., CBD Pet Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Therapeutic Grade, Food Grade), By Application (Joint Pain, Anxiety), By End-use, By Region (North America, Europe, APAC, Latin America, MEA), And Segment Forecasts, 2020 – 2027 (Aug. 2020), https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/cannabidiol-pet-market.

[15] Id.

[16] Virginia Lee, How Big is the Pet CBD Market?, Brightfield Grp. (last updated May 2021), https://blog.brightfieldgroup.com/pet-cbd-market-size.

[17] Am. Pet Products Assoc., APPA 2021-2022 National Pet Owners Survey, 4 https://americanpetproducts.org/Uploads/NPOS/NPOS21-22_TOC.pdf.

[18] Id.

[19] See id., supra note 4.

[20] Id.

[21] Id.

[22] Nat. Ctr. Complementary & Integrative Health, Cannabis (Marijuana) and Cannabinoids: What You Need To Know (last updated Nov. 2019), https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/cannabis-marijuana-and-cannabinoids-what-you-need-to-know.

[23] Id.

[24] John P. Cunha, What is the Function of Endocannabinoids, MedicineNet (July 31, 2020), https://www.medicinenet.com/what_is_the_function_of_endocannabinoids/article.htm (last visited Aug. 4, 2021).

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] LancasterOnline, Hemp in Veterinary Medicine, Interview of Dr. Patti Mayfield, Youtube.com (May 6, 2020), https://youtu.be/mhnosHtE10w.

[29] Id.

[30] See Ahna Brutlag & Holly Hommerding, Toxicology of Marijuana, Synthetic Cannabinoids, and Cannabidiol in Dogs and Cats, 48 Veterinary Clinics North Am. Small Animal Pract. 1087–1102 (2018) doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.07.008.

[31] Id.

[32] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Development & Approval Process (updated Mar. 2, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process.

[33] Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) 1994 Enacted S. 784, 103 Enacted S. 784, 108 Stat. 4325, 103 P.L. 417, 1994 Enacted S. 784, 103 Enacted S. 784 (codified at 21 USCS § 301).

[34] 21 U.S.C § 321(q)(3)(B).

[35] Trish Knight & Peter Reinecke, United Natural Products Alliance (UNPA) Legislative Update, United Natural Products Alliance (July 28, 2021), https://www.unpa.com/unpa-news. H.R. 841 has not been voted on yet by Congress and is still in the introduction phase. Govtrack.com, H.R. 841: Hemp and Hemp-Derived CBD Consumer Protection and Market Stabilization Act of 2021, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/117/hr841 (last visited Sept. 10, 2021) (“This bill is in the first stage of the legislative process. It was introduced into Congress on February 4, 2021. It will typically be considered by committee next before it is possibly sent on to the House or Senate as a whole.”). It currently has a 4% estimate probability of being passed into law. Id.

[36] This, of course, does not include products that are marketed with drug claims.

[37] U.S. Dep’t Health & Human Servs., DIETARY SUPPLEMENT LABELS: KEY ELEMENTS, OIG OEI-01-01-0120 3 (2003), https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-01-00120.pdf (accessed Aug. 4, 2021).

[38] See Inapplicability of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act to Animal Products, 61 Fed. Reg. 17706 (April 22, 1996), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1996-04-22/pdf/96-9780.pdf.

[39] Assoc. Am. Feed Control Offs., Ingredients – Making Pet Food, https://petfood.aafco.org/Ingredients-Making-Pet-Food (last visited Aug. 4, 2021); U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Pet Food (updated Feb. 19, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-food-feeds/pet-food.

[40] While FDA’s regulatory authority over veterinary devices is established, there is no pathway for pre-approval of these devices. See U.S. Food & Drug Admin., How FDA Regulates Animal Devices (updated Jun. 29, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-health-literacy/how-fda-regulates-animal-devices.

[41] Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C.S. § 201(f)(1) (3).

[42] These are two substances frequently included in pet and human supplements to “support joint health.”

[43] Also, there is no pre-approval of medical devices.

[44] See U.S. Food & Drug Admin., How FDA Regulates Animal Devices (updated Jun. 29, 2021), https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-health-literacy/how-fda-regulates-animal-devices.

[45] Assoc. Am. Feed Control Offs., Guidelines on Hemp in Animal Food, https://petfood.aafco.org/labeling-labeling-requirements (last visited Aug. 4, 2021).

[46] See generally Assoc. Am. Feed Control Offs., supra note 39. Ingredient definitions and their common names come into the AAFCO OP through one of three different routes. These include:

- A Food Additive Petition to the FDA (FAP), which is filed with FDA/CVM;

- An FDA/CVM Letter of “No Questions,” which has been issued in response to a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) dossier submitted to CVM by the organization requesting the ingredient; and

- Directly as an AAFCO defined ingredient.

Each of these routes involves some level of safety and utility review by FDA/CVM. Regulators and industry regularly rely upon the AAFCO OP ingredient list for animal foods.

[47] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., FDA Responds to Three GRAS Notices for Hemp Seed-Derived Ingredients for Use in Human Food (Dec. 20, 2018), https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-responds-three-gras-notices-hemp-seed-derived-ingredients-use-human-food (last visited Sept. 10, 2021).

[48] Assoc. Am. Feed Control Offs., Guidelines on Hemp in Animal Food, https://petfood.aafco.org/labeling-labeling-requirements (last visited Aug. 4, 2021).

[49] NASC members produce health supplements for pets, primarily dogs, cats, and horses, not food-producing animals. Nat. Animal Supplement Council, Primary Supplier Members’ Accountability Guidelines (accessed with permission on Aug 4, 2021).

[50] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Small Entity Compliance Guide: What You Need to Know About the FDA Regulation: Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (21 C.F.R. Part 117): Guidance for Industry, https://www.fda.gov/media/100921/download#page (updated Jun. 29, 2021).

[51] Adverse Event: “An Adverse Event is a type of Complaint where a patient has suffered any negative physical effect or health problem that MAY be connected to or associate with use of the product.” Serious Adverse Event: “An Adverse Event with a transient incapacitating effect (i.e. rendering the animal unable to function normally for even a short period of time, such as with a seizure) or non-transient (i.e. permanent) health effect. Transient vomiting or diarrhea do not constitute Serious Adverse Events. A purported Serious Adverse Event requires follow-up with a veterinarian. A layperson diagnosis does not constitute a Serious Adverse Event.” This system contains over 40 billion bytes of data, monitors 6,500+ products and 1,400+ individual ingredients, including CBD, all in real time. NASC has had this system in place since 2004, although it has evolved some over time.

[52] Nat. Animal Supplement Council, supra note 49.

[53] From the author’s personal interview with Bill Bookout, 4/4/2021. Telephone Interview with Bill Bookout, President, National Animal Supplement Council (April 4, 2021).

[54] Id.

[55] An FDA Form 483 is issued to firm management at the conclusion of an inspection when an investigator(s) has observed any conditions that in their judgment may constitute violations of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act and related Acts. U.S. Food & Drug Admin., FDA Form 483 Frequently Asked Questions (Jan. 9, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/inspection-references/fda-form-483-frequently-asked-questions.

[56] Nat. Animal Supplement Council, NASC Labeling & Testing Requirements for Members Marketing Products Containing Hemp or any Hemp Derivatives, NASC Document Control No. 1.30.4 (accessed with permission on Aug. 4, 2021). There are multiple industry groups for human supplements, several of which, like NASC, have drafted hemp guidelines. The Consumer Health Care Products Association has an expansive selection of CDB and Hemp Oil content. The American Herbal Products Association just prepared extensive guidelines relating to hemp and hemp-derived products in June 2021. A review of these guidelines for human supplements (many of these guidelines can only be accessed by group members), is beyond the scope of this article. See, e.g., Consumer Health Care Products Association, https://www.chpa.org/our-issues/dietary-supplements/cbd-and-hemp-oil, and The American Herbal Products Association, https://www.ahpa.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Policies/Guidance-Policies/2021_AHPA_GAP-GMP_Hemp_Guidance_Final.pdf.

[57] Id.

[58] Marcel O. Bonn-Miller, et al., Labeling Accuracy of Cannabidiol Extracts Sold Online, 318 JAMA 1708–09 (2017) (available at doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11909).

[59] Bill J. Gurley, et al., Content versus Label Claims in Cannabidiol (CBD)-Containing Products Obtained from Commercial Outlets in the State of Mississippi, 17 J. Dietary Supplements 599-607 (2020).

[60] Slavik Dushenkov, et al., Phytoremediation of Radiocesium-Contaminated Soil in the Vicinity of Chernobyl, Ukraine, 33 Env’t Sci. & Tech. 469-475 (1999) (available at DOI: 10.1021/es980788+).

[61] See generally Eshetu Shifaw, Review of Heavy Metals Pollution in China in Agricultural and Urban Soils, 8 J. Health & Pollution 8 (June 6, 2018), available at doi:10.5696/2156-9614-8.18.180607.

[62] Telephone Interview with Bill Bookout, President, National Animal Supplement Council (Aug.4, 2021).

[63] Dasilva v. Infinite Prod. Co. LLC, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 46451, 2021 WL 900642; Complaint, Fausett et al. v. Koi CBD, LLC, 2:19-cv-10318 (C.D. Cal. 2019). The Fausett case joined the Dasilva class action suit.

[64] Fla. S. B. No. 182. Fla. Stat. §§ 580.051, 581.217; Fla. Admin. Code §§ 5E-3.003, 5E-3.004, 5E-3.005, 5E-3.020; see also Fla. Dept. Agr. & Consumer Serv., Hemp and Animal Feed, https://www.fdacs.gov/Cannabis-Hemp/Hemp-CBD-in-Florida/Hemp-and-Animal-Feed (last visited Aug. 4, 2021).

[65] Idaho Code § 37-2701. Weedmaps, Is CBD legal in Idaho? (June 28, 2021), https://weedmaps.com/learn/cbd/is-cbd-legal-in-idaho (“Even though hemp-derived CBD became federally legal in 2018, the ultra-low THC formulas remain illegal in Idaho unless they contain zero THC and are manufactured from one of the approved components of the plant, mainly the plant’s mature stalks or sterilized seeds. Any non-FDA approved CBD products with any amount of THC are still considered a controlled substance in Idaho. The only legal exception for medical CBD is Epidiolex, the pharmaceutical grade, FDA-approved CBD oil made by GW Pharmaceuticals.”).

[66] Telephone Interview with Bill Bookout, President, National Animal Supplement Council (Aug. 4, 2021).

Update Magazine

Fall 2021

ELIZABETH (E.B.) BUTTERWORTH STUTTS is in private practice in Maidens, VA. She advises businesses and professionals in the fields of human and veterinary medicine, life sciences, and agriculture. Her practice areas include product development and promotion, licensure, compliance, risk management, telehealth, and commercial contracts. E.B. serves on The Veterinary Products Committee of the Food & Drug Law Institute, the Legal Advisory Board of the Center for Telehealth and e-Law, and is a member of the American Veterinary Medical Law Association (AVMLA) and the Veterinary Virtual Care Association (VVCA).

ELIZABETH (E.B.) BUTTERWORTH STUTTS is in private practice in Maidens, VA. She advises businesses and professionals in the fields of human and veterinary medicine, life sciences, and agriculture. Her practice areas include product development and promotion, licensure, compliance, risk management, telehealth, and commercial contracts. E.B. serves on The Veterinary Products Committee of the Food & Drug Law Institute, the Legal Advisory Board of the Center for Telehealth and e-Law, and is a member of the American Veterinary Medical Law Association (AVMLA) and the Veterinary Virtual Care Association (VVCA).