Food Litigation Trends: New and Undefined Label Claims in 2017

by August T. Horvath, Caroline W. Hudson, Yvonne McKenzie

Part 1: Current Trends and Ingredient Claims

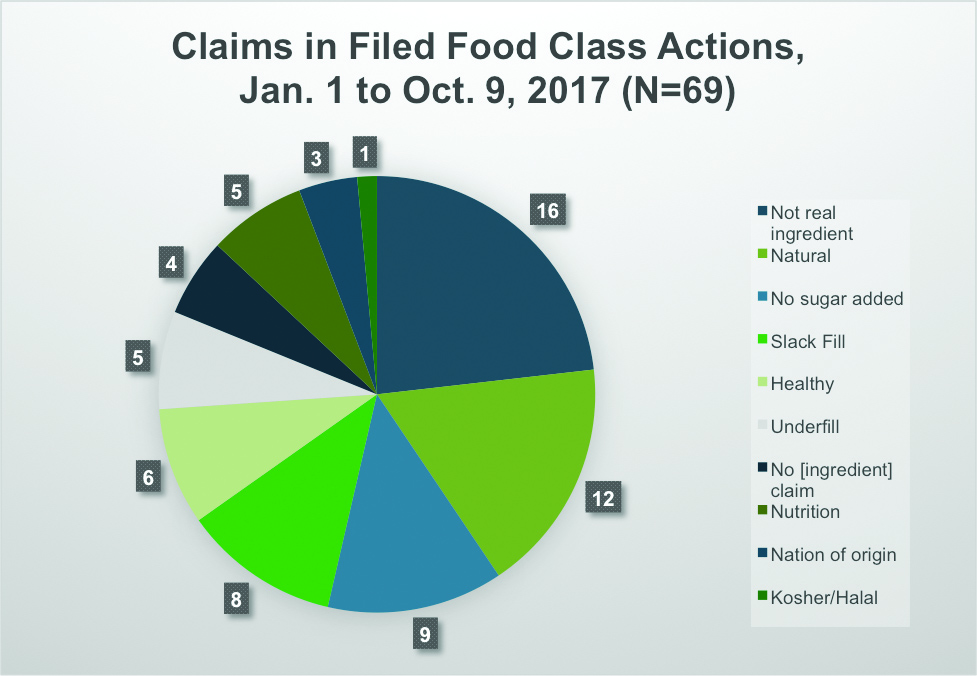

Class-action lawsuits involving the false advertising of food products continue to be one of the most active areas in class litigation. We reviewed cases filed thus far in 2017 to get a sense of the number of filings and their breakdown in terms of subject matter. We wanted to get a sense of the level of activity in these cases as well as which types of cases are most prevalent. Are the “natural” and slack-fill cases that are being widely talked about the most common cases? Are there others to watch out for that have not been getting so much publicity?

We started by scanning various legal news sources, including online class-action tracking sites, for filings from January 1 to October 9, 2017. We tabulated food and beverage advertising class actions that were newly filed in 2017. For purposes of this analysis, we omitted cases that were first filed before 2017 but were removed, transferred, had classes certified, settled, or had key rulings issued in 2017. We omitted cases involving adjacent categories of products, such as pet foods and dietary supplements. We included cases against food service companies such as restaurants, but only to the extent that the cases concerned false advertising of their food offerings. We included cases involving alcoholic beverages. We counted only cases that alleged false advertising or deceptive practices (including, for example, slack fill) with respect to food products, and not cases sounding in privacy or data security, product liability, or other areas.

We started by scanning various legal news sources, including online class-action tracking sites, for filings from January 1 to October 9, 2017. We tabulated food and beverage advertising class actions that were newly filed in 2017. For purposes of this analysis, we omitted cases that were first filed before 2017 but were removed, transferred, had classes certified, settled, or had key rulings issued in 2017. We omitted cases involving adjacent categories of products, such as pet foods and dietary supplements. We included cases against food service companies such as restaurants, but only to the extent that the cases concerned false advertising of their food offerings. We included cases involving alcoholic beverages. We counted only cases that alleged false advertising or deceptive practices (including, for example, slack fill) with respect to food products, and not cases sounding in privacy or data security, product liability, or other areas.

Our coding scheme was based partly on widely discussed categories such as allegations that a product is falsely advertised or labeled as “natural” or that it is deceptively packaged with slack fill. We let other categories emerge from the cases themselves. A case could be coded into multiple categories, but this was rare.

Overall Conclusions

We counted 69 food and beverage advertising class actions in the first 40 weeks of 2017. The chances are that we missed some, despite diligent research. At a rate of 1.7 cases filed per week, in absolute terms, this litigation area clearly is active. We have not extended the analysis back into past years to determine where 2017 fits in the long-term trend. Our impressions as practitioners in the area is that food advertising class actions are at least level with, and perhaps slightly up, compared to the past few years.

We identified ten categories of food and beverage advertising class actions. We expected that claims alleging false “natural” labeling and advertising would top the list, but although “natural” claims were challenged in 12 of the 69 cases, it was only the second highest category. The top category was a bit more amorphous. Rather than challenging a single word or phrase, these cases alleged that the product’s advertising or labeling misrepresented what it was made of. For example, “truffle oil” allegedly contained no truffles; “extra virgin” olive oil was not really extra virgin; and so forth. Almost one quarter—16 of 69—of food and beverage advertising class actions in 2017 thus far have focused on such claims.

In addition, it is worth noting that an additional category, the mirror image of the one just described, could have been folded into it: allegations that a product held itself out as not containing an undesirable ingredient, such as trans fat, when in fact it did contain it. This accounted for a further four cases. Thus, the most prevalent type of food advertising class action currently being filed alleges old-fashioned mischaracterization of what the product is.

Following no-such-ingredient and “natural” cases, the third most common category consisted of cases alleging that the product represented, expressly or by implication, that it had no sugar added. Several of these cases alleged that “evaporated cane juice” should be called “sugar.”

The next most common group of cases (eight of 69) alleged slack fill. Conceptually, these might be grouped with the sixth most common group, which alleged underfill. Both types of cases deal with the amount of product in the package, but whereas slack-fill cases allege that there is a large amount of empty space in the package that deceives consumers into believing there is more product than there is, underfill cases allege that the package contains less product than is stated on the product labeling. We found five cases alleging underfill.

In between the slack-fill and underfill cases, in fifth place, were cases that allege products falsely represented themselves as “healthy”—often by implication rather than explicitly—notwithstanding some aspects of the products that, in the plaintiffs’ view, rendered them not healthy. There were also five cases in which some nutritional aspect of the product was allegedly misrepresented, such as almond milk allegedly holding itself out as nutritionally equivalent to cows’ milk. Finally, a few cases challenged the alleged misrepresentation of a product’s country of origin, usually by arguing that a product’s name, trade dress, or advertising imagery evoked a country or region where it was not actually made. One case alleged that a food misrepresented itself as halal.

In the rest of this article, we’ll describe the major categories of 2017 food advertising class actions in more detail.

Ingredient Claims: Either You’ve Got It or You Don’t

The 20 food advertising class actions that challenged food or beverage products’ characterizations of their ingredients were varied. Highlighting just a few of these cases is perhaps the best way to illustrate the threat posed by these theories to any food or beverage manufacturer.

- In Miller v. Yucatan Foods LP, Case No. BC645421, Superior Court of the State of California, County of Los Angeles, the plaintiff alleged that Yucatan guacamole is labeled “95% avocado; 5% spices” when, in fact, they contain many other ingredients that are neither avocado nor spices, including onion powder, garlic powder, minced onion, evaporated cane juice, citric acid, ascorbic acid, and xanthan gum.

- Fitzhenry-Russell v. Dr. Pepper Snapple Group, Case No. 5:17-cv-00564-NC and Fitzhenry-Russell v. The Coca Cola Company, Case No. 5:17-cv-00603 (N.D. Cal.), are two cases filed by the same plaintiffs against makers of ginger ales, alleging that the products contain no real ginger. The plaintiff alleged that the deception arose not just from the designation of these beverages as ginger ales but also from explicit claims that they are “made with real ginger.” In fact, the plaintiff alleged, the ginger flavor in these products is provided by a chemical that mimics ginger flavor.

- In Silva v. Unique Beverage Company LLC, Case No. 3:17-cv-00391-HZ (D. Or.), the plaintiff alleged that a flavored carbonated water designated “coconut” flavor actually contained no coconut.

- A trio of truffle oil cases, Schiffman v. Urbani Truffles USA Inc., Case No. 2:17-at-00470 (E.D. Cal.), Brumfield v. Trader Joe’s Co., Case No. 1:17-cv-03239 (S.D.N.Y.), and Quiroz v. Sabatino Truffles New York LLC, Case No. 8:17-cv-00783 (C.D. Cal.), allege that truffle infused olive oils are falsely held out as containing real truffles when actually they contain artificial truffle flavors.

- In the latest of several cephalopod cases, Lejbman v. Transnational Foods Inc., Case No. 3:17-cv-01317 (S.D. Cal.), purported tins of octopus are alleged to in fact contain squid, an allegedly cheaper and less tasty eight-armed delicacy.

Part 2: Evolving Theories and Categories of Claims

The explosion in consumer class action litigation over food and beverage product labeling has been well-documented. These cases typically challenge label claims that lack settled regulatory definitions, or where consumers may interpret the labeling or advertising at issue in different ways. Much has been made of the repetitive, “cut-and-paste” nature of many of these filed complaints. At the same time, there have also been noteworthy shifts in litigation theories over the years as plaintiffs’ strategies in this area have evolved and new categories of claims are challenged.

“All Natural” and “Natural”

Food and beverage class action activity initially centered on the claim “all natural,” and variations on this phrase. In a crowded field, “natural” stands out as the quintessential undefined label claim. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has historically declined to define the term, deferring instead to a long-standing non-binding policy.1 In 2015, the agency sought public comment on whether and how it should define “natural.”2 Since then, FDA has not taken action on the comments received, although FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb recently stated that FDA is looking at how to define “natural” more uniformly.3 In the meantime, consumer plaintiffs have continued to file a steady stream of purported class actions alleging the term is misleading when used on products that contain genetically modified organisms (GMOs) or other “artificial” and “synthetic” ingredients and substances. A few courts have stayed “natural” cases in the past year on primary jurisdiction grounds,4 but others have declined to issue a stay in the absence of a timeline for action from FDA.5

In some ways, “natural” cases continue to follow a well-worn path: plaintiffs typically allege that a product cannot be “natural” if it contains certain ingredients that are highly processed, sourced from “synthetic” substances, or fermented using GMOs.6 Plaintiffs often cite other regulations to identify a substance as “synthetic,” including USDA’s National Organic Program list of “synthetics allowed.”7 Examples of these “synthetic” ingredients range from B vitamins to xanthan gum.

On the other hand, plaintiffs are also adopting newer tactics to challenge “natural” on product labels. Some plaintiffs have engaged third-party laboratories to test products for trace residues of pesticides and other “unexpected” ingredients. News reports, stories, and opinions issued by international bodies about the potentially harmful nature of certain substances can also inform and trigger class action filings. A recent spate of filings over the presence of glyphosate in food products provides one example of this trend. Some of these cases have been dismissed, including several over General Mills’ products that are “made with 100% natural whole grain oats,” but allegedly contain trace amounts of glyphosate. One court in particular emphasized that the claim relates only to oats, while the alleged glyphosate content falls well below the permitted amount for organic products.8 We expect to see more cases filed citing “testing” and pronouncements about harmful, “unexpected” substances.

Separately, plaintiffs are also reaching further back into the supply chain to attack “natural” claims where the product incorporates meat or dairy products sourced from cows that may have been given genetically modified feed or treated with certain hormones. In these cases, the defendant manufacturers generally have not made claims on-pack about the presence or absence of GMOs or hormones. Even so, plaintiffs allege that the products must be “unnatural” where these substances and practices could appear somewhere in the supply chain.9 Manufacturers have argued that such “daisy-chained” logic cannot withstand scrutiny,10 but courts have yet to rule on their motions to dismiss. Stay tuned for developments on these cases, as upcoming rulings may determine whether plaintiffs file similar claims based on this reasoning.

Slack Fill

Plaintiffs continue to bring claims over the empty space in a product container, referred to as “slack fill.” In these cases, plaintiffs generally allege that the packaging misleads consumers into believing that there are more items inside than the product actually contains, and that any such space is “non-functional.” Some slack fill is permitted under FDA regulations—for example, space may result from unavoidable product settling, or may protect the contents of the package.11 Certainly consumers can always read the number of ounces printed on the packaging to determine the exact amount of product contained inside. Regardless, many courts have denied manufacturers’ motions to dismiss slack fill cases,12 and some have settled for as much as $12 million.13

As a result, we expect to see slack fill filings continue, while consumer plaintiffs further expand the list of potential targets to include more products outside the food and beverage space.14 In the meantime, manufacturers may consider disclosing the exact number of items in each package on the product label where possible; adding clear sections of package so the product contents are visible; disclosing clear product “fill” lines; or adding statements that explain the product may settle in transit.

Healthy Claims

Another food claim that continues to generate interest from the plaintiffs’ bar is “healthy.” Unlike “natural,” “healthy” is an FDA defined term. When used as an implied nutrient content claim, healthy is defined as a food low in fat, cholesterol and sodium, and containing at least 10 percent of one or more qualifying nutrients. Prior to 2016, FDA issued a slew of Warning Letters attacking manufacturers for labeling their foods as healthy, usually because they were not low in fat. These Warning Letters spurred significant consumer class action litigation, as is usually the case.

Perhaps the most publicized “healthy” litigation triggered by one of these Warning Letters involved snack bars manufactured by KIND. Because the snack bars contain nuts, they were not low in fat, and therefore failed to qualify as “healthy” under the FDA definition in the regulations. KIND made changes to their labeling in response to the Warning Letter, but also challenged FDA on its outdated definition of “healthy.” Not all fats are created equal, KIND argued, and some fats, such as those found in nuts and avocados, are beneficial and support good health. KIND filed a Citizen Petition in support of its position and urged FDA to reconsider the current definition of “healthy.”

FDA ultimately allowed KIND to use the term “healthy” on its labels and agreed that the definition of “healthy” needed retooling. It also solicited public comments on the issue, and, in September 2016, issued non-binding guidance that sets out situations where the agency will exercise enforcement discretion with respect to the term “healthy.” Notably, products labeled as “healthy” that are not low in fat may still use the term provided that (1) the amounts of mono and polyunsaturated fats are declared on the label and (2) the amounts declared constitute the majority of the fat content. FDA has yet to issue any final, revised regulation.

Although FDA ultimately sided with KIND, the company still had to endure significant litigation that garnered significant publicity. Starting in 2015, a dozen or so consumer class actions were filed around the country and consolidated in a multidistrict litigation pending in the Southern District of New York. In re: KIND LLC “Healthy and All Natural” Litigation, 15-MD-2645 (S.D.N.Y.). Brought under the familiar litany of state consumer protection laws, the plaintiffs argued that KIND’s use of the term “healthy” was misleading because the product did not meet the FDA definition under the regulations. While a motion to dismiss was pending, the plaintiffs withdrew their “healthy” claims in light of FDA’s about face on the use of “healthy” on the KIND bar labels. A good result for KIND on these claims, but the litigation against the company also involved other challenges to their label, which are continuing in the courts.

Another wave of recent litigation involving the term “healthy” focuses on the use of added sugar in products advertised or marketed as healthy and nutritious. In 2016, three putative class actions were filed in the federal court in the Northern District of California against manufacturers Post, Kellogg, and General Mills. Plaintiffs argued that the cereals and cereal bars produced by these companies contain “excess” added sugars, which are toxic and increase serious health risks such as strokes and heart attacks. Therefore, they claimed, the defendants’ products are not healthy or nutritious as advertised. The cereal manufacturers filed motions to dismiss in each of these cases, with mixed results. In the case against Kellogg, the court dismissed the Complaint under Rule 9(b) based on the plaintiff’s failure to plead how much added sugar the products contained and how much added sugar is “excessive” or unhealthy. Hadley v. Kellogg Sales Co., 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 40825 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 21, 2017). But a different court confronted with a virtually identical Complaint against Post denied a motion to dismiss, finding the pleading was sufficient to allege a viable claim. Krommenhock v. Post Foods, LLC, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 84359 (N.D. Cal. June 1, 2017). In the third case, the court has yet to rule on the pending motion. Truxel v. General Mills Sales, Inc., No. 4:16-4957 (N.D. Cal.).

Sugar Claims

The amount of added sugar in food has been a recent focus for FDA. In May 2016, FDA revised the Nutrition Facts labeling for foods, requiring that companies specifically disclose the amount of added sugars in the products. FDA commented that “[s]cientific data shows that it is difficult to meet nutrient needs while staying within calorie limits if you consume more than 10 percent of your total daily calories from added sugar, and this is consistent with the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.” https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm385663.htm. Other organizations, such as the World Health Organization and the American Heart Association, have similarly focused on added sugars, recommending that individuals keep their added sugar intake to under five percent.

Regulators are not the only ones focused on added sugars. Judging from the increase in cases challenging added sugar labeling, plaintiffs’ attorneys are too. Several recent cases attack “no added sugar” labeling on foods like juice and applesauce. Plaintiffs in these cases claim that the foods fail to meet regulations that dictate when a “no added sugar” claim can be used. These regulations include 21 C.F.R. 101.60(c)(2)(iv), which prohibits the use of phrases like “no added sugar” unless “the food that it resembles and for which it substitutes normally contains added sugars” and 21 C.F.R. 101.60(c)(2)(v), which requires a food bearing a “no added sugar” claim contain a disclaimer that the food is not “low calorie.”

Some of these cases have been dismissed. For example, the court in Major v. Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc., 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 23542 (N.D. Cal. Feb. 26, 2015) granted summary judgment after plaintiff testified at her deposition that she knew that the cranberry juice she purchased was not low calorie. The Court reasoned that she could not have relied on the absence of that disclaimer, and dismissed the case. This decision was recently upheld by the Ninth Circuit. 2017 U.S. App. LEXIS 8140 (9th Cir. May 8, 2017).

Another notable case is Wilson v. Odwalla, Inc. Here, plaintiffs argued that other comparable juices did not typically contain added sugars. Thus, it was misleading for defendants to label their juices as containing “no added sugar.” The key issue the Court grappled with was how broadly to define 21 C.F.R. 101.60(c)(2)(iv). Plaintiffs, naturally, wanted a narrowly defined substitute product, while defendants advocated for a more broad definition. The district court declined to grant Odwalla’s motion to dismiss, stating that it was not willing to adopt defendants’ definition at this stage in the case. 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 117090 (C.D. Cal. June 28, 2017).

In addition to cases involving “no added sugar” claims, there has been an increase in cases challenging the use of “evaporated cane juice” as an ingredient on food labels. This is largely due to the final guidance issued by FDA in 2016 that stated that the term “evaporated cane juice” is misleading and that companies should make clear on their labels that evaporated cane juice is sugar. Several of the recent cases post-FDA guidance have denied motions to dismiss, or the cases have settled. See, e.g., Swearingen v. Santa Cruz Natural, Inc., 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 109432 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 17, 2016) (motion to dismiss granted in part) (now settled); Swearingen v. Late July Snacks LLC, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 69280 (N.D. Cal. May 5, 2017) (motion to dismiss granted in part, but California consumer protection claims survive).

Country of Origin Claims

Class actions focused on claims about the origin of a food or beverage have also been on the rise. For example, there has been an uptick in the number of cases challenging “Made in the U.S.A.” claims. Although FTC maintains exclusive enforcement authority over these claims under the FTC Act, private plaintiffs have used state consumer protection laws or the California “Made in the U.S.A.” statute (California Business and Professions Code 17533.7) to bring class actions against food companies and other consumer product manufacturers. Many cases have settled, although some manufacturers have held their ground. For example, a putative class action was filed against Rockstar, Inc., a maker of energy drinks that are advertised as being “Made in the U.S.A.” Plaintiffs argued that several ingredients in their drinks, including taurine, guarana seed extract, and milk thistle extract, were foreign sourced. The Court granted Rockstar’s motion to dismiss, finding that plaintiffs failed to plead with specificity where the foreign sourced ingredients were made and what percentage of the product was comprised of foreign-sourced ingredients. Alaei v. Rockstar, Inc., 224 F. Supp. 3d 992 (S.D. Cal. 2016).

More companies may choose to challenge lawsuits attacking their use of “Made in the U.S.A.” claims in light of the recent revisions to the California “Made in the U.S.A.” statute. Effective January 1, 2016, the California statute now allows “Made in the U.S.A.” claims for products that contain foreign components or ingredients so long as the foreign content is five percent or less of the products’ wholesale value (or up to 10 percent of the value if the manufacturer can prove the materials or ingredients are not available in the United States). This significantly relaxes the standard for “Made in the U.S.A.” claims under California law, which had previously required that essentially 100 percent of the product ingredients or components originate in the United States.

Many beer and spirits manufacturers have also faced class action litigation around the origin of their products. In these cases, plaintiffs allege that the place where the alcohol is brewed is of value to them, and that the labels at issue misrepresent the geographic origin of the products to justify a price premium. Several of these cases have been dismissed early, usually on grounds that a reasonable consumer would not be misled about the origin of the product. See e.g., Bowring v. Sapporo U.S.A., Inc., 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 32333 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 10, 2017); Dumas v. Diageo PLC, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 46691 (S.D. Cal. Apr. 6, 2016). Others have not, largely because the disclaimers on the label disclosing where the beer was brewed was not conspicuous enough or was confusing and unclear. See Broomfield v. Craft Brew Alliance, 2017 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 142572 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 1, 2017) (denying in part motion to dismiss).

Defenses and Risk Mitigation Strategies

Courts allow many of these cases to move past the motion to dismiss stage, but there are several defensive strategies companies can consider. Certainly some of these lawsuits are open to challenge on the merits—if no reasonable consumer would share the plaintiff’s view, then the case should not move forward.15 Similarly, if the packaging discloses enough information such that consumers cannot reasonably be misled, then the complaint should be dismissed.16 In some circumstances, courts have found that plaintiffs’ claims are preempted by federal regulations, which require the label to appear as-is, or that a state consumer protection law otherwise provides safe harbor. A few other courts have agreed with food manufacturers that FDA should decide the specific question at issue in the case, and stayed or dismissed the matter on primary jurisdiction grounds.

Other arguments can be raised at the class certification stage. Courts are split on whether the “ascertainability” of a class is a valid criterion to consider when certifying a class, but arguments based on whether it is feasible to accurately determine who qualifies as a class member may be useful depending on the jurisdiction.17 Defendant manufacturers can also pick apart the methods and models used to calculate the damages incurred by various class members. If damages cannot be accurately calculated, plaintiffs may be left with only the opportunity to receive injunctive relief, or no relief, if class members lack a common injury. Or defendants can ask whether the named plaintiff is the right person to bring the lawsuit and challenge the adequacy of the class representative.

Finally, there are a few risk mitigation strategies that companies can adopt now—before a complaint is filed. In particular, regular communication between research and development, regulatory, marketing, and legal teams can be crucial to understanding the potential risks associated with particular claims up front. Certain claims and labeling statements often appear attractive from a marketing and competitive standpoint. That said, communications with R&D, regulatory, and legal can help ensure such claims are appropriately tailored and adequately substantiated, while carefully weighing any potential value against existing litigation risks. Even long-standing claims are open to challenge by consumer plaintiffs, so these discussions should be ongoing and in conjunction with regular review and reassessment of existing labels. Members of the legal team can inform these discussions with regular monitoring of case filings, warning letters, guidance documents, and other regulatory activity to stay on top of developments.

- FDA considers “natural” on a food label to be truthful and non-misleading when “nothing artificial or synthetic (including all color additives regardless of source) has been included in, or has been added to, a food that would not normally be expected to be in the food.” FDA, Food Labeling: Nutrient Content Claims, General Principles, Petitions, Definitions of Terms, 58 F.R. 2302, 2407 (Jan. 6, 1993). FDA also defines “natural flavor” by regulation. See 21 C.F.R. 101.22(a)(3).

- 80 F.R. 69905, 2015 WL 6958210 (Nov. 12, 2015); see also 80 F.R. 80718 (Dec. 28, 2015) (extending the comment period to May 10, 2016).

- Wall Street Journal, Global Food Forum, “FDA Commissioner Wants Closer Look at Health Claims on Packaging,” Oct. 10, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/fda-commissioner-wants-closer-look-at-health-claims-on-packaging-1507673335.

- See, e.g., Kane v. Chobani, LLC, 645 Fed. Appx. 593 (9th Cir. 2016); Rosillo v. Annie’s Homegrown, Inc., Case No. 17-cv-02474 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 17, 2017).

- See, e.g., Madrigal v. Hint, Inc., Case No. 2:17-cv-02095 (C.D. Cal. June 23, 2017).

- See e.g., Campbell v. Annie’s Homegrown, Inc. et al, Case No. 3:17-cv-01736 (S.D. Cal. Aug. 28, 2017).

- 7 C.F.R. 205.605(b).

- In re General Mills Glyphosate Litigation, Case No. 0:16-cv-02869 (D. Minn. July 12, 2017).

- See, e.g., Stanton v. Sargento Foods, Inc., Case No. 3:17-cv-02881 (N.D. Cal. May 19, 2017); Popedskar v. Dannon Company, Inc. Case No. 7:16-cv-08478 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 31, 2016); Forsher v. Boar’s Head Provisions Co. Inc., Case No. 4:17-cv-04974 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 25, 2017).

- Stanton v. Sargento Foods, Inc., (N.D. Cal.).

- 21 C.F.R. § 100.100.

- See, e.g., White v. Just Born, Inc., Case No. 2:17-cv-04025 (W.D. Mo. Feb. 16, 2017).

- Hendricks v. Starkist Co., Case No. 13-cv-00729 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 29, 2016).

- See e.g., Lau v. Pret A Manger (USA) Limited et al., Case No. 1:17-cv-05775 (S.D.N.Y. July 31, 2017); Daniel v. Tootsie Roll Industries, LLC, Case No. 1:17-cv-07541 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 3, 2017).

- Sugawara v. Pepsico, Inc., No. 08-cv-1335, 2009 WL 1439115 (E.D. Cal. 2009) (“[A] reasonable consumer would not be deceived into believing that the product in the instant case contained a fruit that does not exist.”)

- Fermin v. Pfizer Inc., Case No. 1:15-cv-02133 (E.D.N.Y. 2016) (noting the packages “clearly displayed the total pill-count on the label” and the claim “does not pass the proverbial laugh test”).

- The Supreme Court recently declined to take on Conagra’s challenge to class certification in a suit over “natural” claims on ascertainability grounds. Conagra Brands Inc., f/k/a ConAgra Foods Inc., v. Robert Briseno et al., Case No. 16-1221. As a result, there remains a circuit split: courts in the First, Third, Fourth, and Eleventh Circuits have adopted the heightened ascertainability requirement; the Second, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits have rejected an “administrative feasibility” prerequisite.

Update Magazine

November/December 2017