The QMSR Transition, New FDA Guidance, and Their Impacts on Active Implantable Medical Devices

By Sangeeta Abraham and James F. Brennan, III

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates medical devices and classifies them as Class I, Class II, and Class III, which is determined, in part, by their intended use. This coming year on February 2, 2026, FDA will transition the existing Quality System Regulation (QSR) defined in 21 CFR 820 to the Quality Management System Regulation (QMSR).[1] The current good manufacturing practices in the QSR will be amended to align more closely with international regulations by incorporating by reference ISO 13485:2016, “the international consensus standard for Quality Management Systems for medical devices used by many other regulatory authorities around the world.”[2]

The main difference between the existing QSR and upcoming harmonized QMSR is the explicit integration of risk management throughout the regulation. As such, medical device manufacturers should take a risk-based approach throughout the entirety of their quality management system in addition to product design risk management. This type of holistic risk-based approach concerns itself with risks that are inherent to the total product lifecycle, including elements such as management responsibilities, purchasing requirements, and process monitoring, among others. While the QMSR regulation is substantially similar to the existing QSR,[3] manufacturers are expected to consider updating their internal quality systems in response to this transition. Many manufacturers in the United States, especially those marketing medical devices outside the country, may already be in compliance with ISO 13485:2016 in addition to the QSR, but some domestic-only manufacturers may have to make additional changes to comply.

In preparation for this transition, FDA has issued some new guidance documents, including one pertaining to premarket approval (PMA) applications entitled “Quality Management System Information for Certain Premarket Submission Reviews,” which was issued as draft guidance in October 2025.[4] This guidance more explicitly communicates the risk management activities expected to be demonstrated by a manufacturer than what is currently described. For example, this draft guidance document contains descriptive language about requirements for the purchasing process, such as:

Establish criteria for evaluation and selection of suppliers for the subject device, based on the supplier’s ability to provide product that meets requirements, based on the supplier performance, based on the effect of the purchased product on the quality of the device, and proportionate to the risk associated with the device.[5]

In general, Class III devices that require a PMA are those that “support or sustain human life, are of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health, or which present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury.”[6] PMA approval is based on a determination by FDA that sufficient valid scientific evidence is present to provide a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the device’s intended use. Prior to approving a PMA, FDA conducts a pre-approval inspection to assess the company’s systems, methods, and procedures for the specific device to ensure that the firm’s quality management system is effectively established.[7]

A PMA is needed before certain medical devices can be marketed in the United States and, as such, manufacturers of complex implantable devices, such as neurostimulators and cardiac pacemakers, should consider FDA’s new guidance documents.

Certain medical devices, such as sacral nerve and spinal cord stimulators (SCS), are Class III medical devices that require a PMA. A neurostimulator applies precisely timed electrical pulses at certain locations of nerve tissue to initiate a desired response. An implantable neurostimulator system typically includes an implantable pulse generator (IPG), an electrical lead or leads that electrically connect the IPG to nerve tissue, and devices for patient control and clinician programming and monitoring. The IPG is the “brains” of the system that administers small electrical pulses through the leads and is often referred to as the neurostimulator itself.[8]

In general, an IPG consists of a hermetically sealed metallic canister that houses electronic circuitry and a battery for purposes of delivering these electric pulses. SCS devices, for example, utilize these electric pulses to treat certain chronic intractable pain of the trunk and limbs and have been the subject of dozens of recent lawsuits.[9] While we discuss SCS devices specifically, the general concepts can be applied to a wide array of cardiac devices and neurostimulators more broadly.

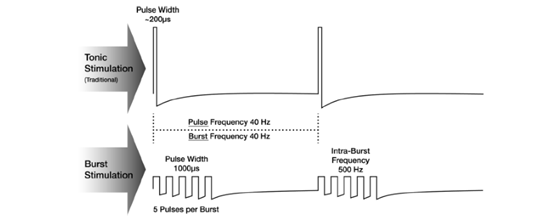

Traditional SCS devices produce tonic electrical waveform stimulation where electrical pulses are delivered at a constant frequency, pulse duration, and amplitude. Other alternate waveforms are often used, such as burst stimulation, where groups of pulses are delivered at a higher frequency and lower amplitude than tonic stimulation. These waveforms are typically applied either continuously or cycled, where the waveform is applied at selected on and off time intervals. These two stimulation delivery methods are referred to as continuous mode and cycled mode.

Examples of SCS waveforms. Tonic stimulation provides a consistent stream of pulses at a set frequency, pulse width, and amplitude. Burst stimulation delivers groups of pulses at a lower amplitude and a higher frequency than tonic stimulation. Bursts of pulses are followed by pulse-free periods.[10]

A clinician can communicate with and program an IPG via an external device such as a wand, which is placed over the device to establish a wireless link between a computer and the IPG. Parameters, such as the pulse frequency, duration, cycle time, amplitude range, and stimulation type (e.g., tonic or burst), can be stored in the IPG for later use by the patient. A desired therapy pattern is called a program, and multiple programs that contain unique therapy parameters can be stored within a given IPG.

A patient can often communicate with the IPG that is implanted via a specialized software application installed on an external device such as a tablet or their cell phone. Patients can use this application to turn therapy on and off, adjust stimulation strength, and activate or modify programs created by the clinician.

Many implantable medical devices, including pacemakers and neurostimulators, have components that are critical to the functionality of the device which are purchased from external suppliers. These components include items such as sensors and batteries.

Pacemakers and neurostimulators can have sensors to indicate the presence of a large magnetic field. These sensors allow a patient or clinician to temporarily control the device by holding a magnet over the IPG to, for example, turn therapy on or off, trigger a fixed-rate stimulation mode, or initiate controller pairing. Some equipment in home, work, and public environments can generate a magnetic field that is strong enough to activate these internal sensors, so patients should avoid lingering near these sources, such as anti-theft gates, arc welders, and induction furnaces.

The longevity of an IPG battery is dependent on many factors, such as program settings, the electrical impedance between active electrodes, and hours of device use. Battery longevity is a critical parameter that gets characterized by both the battery supplier as well as the medical device company incorporating the battery into their product.

Devices with non-rechargeable batteries will need to have the entire IPG replaced when the battery nears depletion. When this is done, the implanted leads can often remain within the patient and be connected to the new IPG. An IPG is typically designed to transmit a warning signal to clinicians and the patient, called an elective replacement indicator, that indicates the battery is nearing depletion and an IPG replacement procedure should be scheduled.

In the examples above, both the battery and the sensors are critical components of an active implantable medical device, and, according to FDA’s new draft guidance document, the requirements for purchasing and verifying these components would need to be explicitly detailed in the PMA application such that the process for evaluating and selecting the supplier is proportionate to the risk associated with it. While this process may not be substantially different than what manufacturers already provide as part of their purchasing controls in their PMA submission, an additional layer of detail is that under the QMSR, supplier audit reports can now be inspected by FDA.[11] This means the purchasing controls information provided in a PMA application may be checked against the supplier audit reports a manufacturer maintains as part of its documentation to ensure compliance.

The upcoming QMSR transition will likely have far-reaching effects for manufacturers and regulators alike and is anticipated to allow for quicker access to newly developed medical devices while maintaining FDA’s expectations for an effective quality management system and robust supplier quality programs.[12] Medical device manufacturers should be preparing for this transition by assessing their existing quality and risk management systems to ensure compliance. It is yet to be seen how FDA’s inspection process will differ, but maintaining appropriate levels of documentation to demonstrate their risk-based approaches is critical for medical device manufacturers.

[1] When referring to 21 CFR 820 as amended, effective February 2, 2026, FDA uses the term “QMSR.”

[2] U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Quality Management System Regulation: Final Rule Amending the Quality System Regulation – Frequently Asked Questions” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/quality-system-qs-regulationmedical-device-current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmp/quality-management-system-regulation-final-rule-amending-quality-system-regulation-frequently-asked

[3] Federal Register, “Medical Devices; Quality System Regulation Amendments” https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/02/2024-01709/medical-devices-quality-system-regulation-amendments

[4] Quality Management System Information for Certain Premarket Submission Reviews, Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, https://www.fda.gov/media/189345/download

[5] Quality Management System Information for Certain Premarket Submission Reviews, Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff, https://www.fda.gov/media/189345/download

[6] U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Premarket Approval (PMA)” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/premarket-submissions-selecting-and-preparing-correct-submission/premarket-approval-pma

[7] U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Medical Device Premarket Approval and Postmarket Inspections – Part III: Inspectional” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/quality-and-compliance-medical-devices/medical-device-premarket-approval-and-postmarket-inspections-part-iii-inspectional

[8] For general neurostimulator background information, see Krames ES, Peckham ES, Peckham PH, Rezai AR (Eds.). Neuromodulation: Comprehensive Textbook of Principles, Technologies, and Therapies, 2nd Edition, Volumes 1–3. Academic Press, 2018. ISBN-13: 978-0128053539.

[9] FDA Sued Over Allegedly Defective Spinal Cord Stimulators| Law.com

[10] Figure 3 in Slavin KV, North RB, Deer TR, Staats P, Davis K, Diaz R. Tonic and burst spinal cord stimulation waveforms for the treatment of chronic, intractable pain: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016 Dec 1;17(1):569. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5131423/figure/Fig3/.

[11] U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Quality Management System Regulation: Final Rule Amending the Quality System Regulation – Frequently Asked Questions” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/quality-system-qs-regulationmedical-device-current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmp/quality-management-system-regulation-final-rule-amending-quality-system-regulation-frequently-asked

[12] Federal Register, “Medical Devices; Quality System Regulation Amendments” https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/02/2024-01709/medical-devices-quality-system-regulation-amendments

FDLI is a nonprofit membership organization that offers education, training, publications, and professional networking opportunities in the field of food and drug law. As a neutral convener, FDLI provides a venue for stakeholders to inform innovative public policy, law, and regulation. Articles and any other material published in Update represent the opinions of the author(s) and should not be construed to reflect the opinions of FDLI, its staff, or its members. The factual accuracy of all statements in the articles and other materials is the sole responsibility of the authors.