Freshly Squeezed: Orange Book History and Key Updates at 45

By Crystal Canterbury*; Katelyn Nguyen**; Andrew Coogan***;

*U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Office of Generic Drugs (OGD), Office of Generic Drug Policy (OGDP), Division of Legal and Regulatory Support (DLRS)

**FDA, CDER, OGD, OGDP, Division of Orange Book Publication and Regulatory Assessment (DOBPRA)

*** FDA, CDER, OGD, OGDP, DLRS, Patent and Exclusivity Team (PET)

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Alicia Chen, Timothy H. Kim, Kendra Stewart, and Harvey Greenberg, all currently or formerly of CDER/OGD/OGDP/DOBPRA, for their contributions to the historical background of this paper. The authors would also like to thank Kristin Davis, Christopher Pruitt, Mary Alice Hiatt, Colleen M. Lee, Alicia Chen, and Timothy H. Kim, all employees within CDER/OGD/OGDP, for their valuable insights and feedback on drafts of this paper.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as the position of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

I. Introduction

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (commonly known as the “Orange Book”), which identifies drug products approved by FDA on the basis of safety and effectiveness, also contains therapeutic equivalence evaluations for approved prescription drug products that are multisource (in general, meaning there are pharmaceutical equivalents available from more than one manufacturer). The Orange Book publication is designed to serve as public information and advice to state health agencies, prescribers, and pharmacists to promote public education in the area of drug product selection and to foster containment of health care costs. Although the first draft edition (1979) and the current 45th Annual Edition (2025) are fundamentally similar in their goals, the Orange Book is constantly in flux, with new product information (e.g., approvals, patents) posted daily and many other substantive updates made over its 45‑year history. Due in part to the ever-increasing number of listed products, some changes have been applied prospectively rather than retroactively, resulting in the current Orange Book containing information reflecting a mixture of certain “old” and “current” practices. A summary of the substantive updates that have been made to the Orange Book over its history has never before been collected in one location, previously requiring users with questions about such changes to identify numerous statutes, Federal Register notices, annual Orange Book Prefaces, and other internal content in order to understand the bases for all these changes.

As the Orange Book celebrates its 45th year, we are providing such a summary of the Orange Book’s historical development and highlighting key changes with a reference to the relevant sources. First, we explain the historical backdrop for the Orange Book, including key federal statutory changes and the patchwork of state-level developments and requests to FDA that spurred FDA’s independent development of a compendium of approved drugs with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. Second, we describe how FDA initially envisioned the Orange Book and how Congress later required FDA to maintain and update a list of approved drugs with therapeutic equivalence evaluations—a requirement satisfied by the Orange Book and its supplements. Finally, we detail the timing of and certain implications for five categories of major changes to the Orange Book over the last 45 years.

II. Orange Book History

A. Background

The Orange Book was developed in response to changing thinking and legal landscapes at the federal and state levels. As the federal government evaluated increasing numbers of drugs for safety and efficacy and began providing certain abbreviated pathways for identical, related, or similar drug products, states were also rethinking their laws in ways that would expand their residents’ access to affordable drug products and alter the legal landscape for pharmacists dispensing medication.

Under the Food and Drugs Act of 1906 (also called the Pure Food and Drug Act), pharmaceuticals sold in interstate commerce were not subject to any premarketing approval, with the law only prohibiting in interstate commerce adulterated and misbranded drugs (narrowly defined) and subjecting such drugs to criminal sanctions and seizure.[1]

After the enactment of the Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) in 1938, manufacturers of new drug products needed to submit an application to FDA before marketing a drug product—with the application automatically approved if the FDA did not act on it within 60 days.[2] Between 1938 and 1962, if a drug product obtained approval, FDA also considered identical, related, or similar drug products to be covered by that approval; such identical, related, or similar products were marketed without independent approvals. In 1962, the Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments amended the FD&C Act to require that new drug products also be shown to be effective in order to obtain approval of a new drug application (NDA).[3]

After the enactment of the Kefauver–Harris Drug Amendments, FDA initiated the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) to evaluate the effectiveness of drug products that had been approved between 1938 and 1962 solely on the basis of safety. DESI also covered identical, related, or similar products that had entered the market without approval. If drug products were determined to be effective for one or more indications, manufacturers that were already marketing under an NDA were required to submit a supplement to update the application and revise the product labeling as necessary. Manufacturers of drug products that were identical, related, or similar were required to submit applications for their drug products.

In 1968, FDA recognized that “there are circumstances in which the submission of an abbreviated new drug application containing designated items of information will be sufficient for approval of a required application” and thus proposed a rule allowing “abbreviated new drug applications” as a vehicle for approval of certain drugs affected by the DESI review.[4] In 1970, FDA finalized the rule with minor revisions, thus establishing a regulatory pathway for submission of abbreviated applications under Section 505(b) of the FD&C Act for these drugs.[5] In 1984, the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (the Hatch–Waxman Act)[6] amended the FD&C Act to establish the abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) process we still have today, with applications submitted under Section 505(j) of the FD&C Act, which in general requires that the proposed drug product be pharmaceutically equivalent, bioequivalent, and therapeutically equivalent to a previously approved listed drug.

The legal backdrop to the Orange Book evolved in parallel with other external circumstances. During the late 1960s as FDA was developing an initial abbreviated application process at the national level, states were still operating under “anti-substitution” laws requiring pharmacists to fill prescriptions as-written, making it a crime for a pharmacist to dispense an identical, related, or similar drug in place of a brand-name drug.[7] As states began searching for ways to encourage cost-effective substitution, they adopted a patchwork of positive formulary and negative formulary approaches.[8] (A positive formulary limits drug substitution to drugs on a specific list, whereas a negative formulary permits substitution for all drugs except those prohibited by a specific list.) In developing their positive or negative formularies, states looked to FDA—in particular, a list that FDA had published on June 20, 1975, as part of proposed rulemaking concerning how FDA would define “bioavailability” and “bioequivalence,” with the list comprised of drugs, other than antibiotics, with known or potential bioequivalence problems for which FDA intended to establish a bioequivalence requirement.[9]

FDA promptly identified a “concern[]” about how the 1975 list was used by state drug procurement programs as it was not intended to “include all marketed drug products that are subject to an approved NDA or [abbreviated application]” and should not have been interpreted “as being a total listing of drug products that FDA has approved for marketing.”[10] Because “some State agencies, individual pharmacists, and physicians . . . interpreted [FDA’s June 20, 1975] list as a final official compilation of noninterchangeable drug products and . . . refused to purchase generic products of any listed drug,” in early 1976, FDA sought to “aid purchasers” by clarifying and expanding the 1975 list.[11] First published in January 1976 and revised periodically afterward, the revised list, Holders of Approved New Drug Applications for Drugs Presenting Actual or Potential Bioequivalence Problems, which became popularly known as the FDA “Blue Book” due to its blue cover, listed all NDA-holders and pre-Hatch–Waxman ANDA (PANDA) holders for drugs appearing on the original June 20, 1975 bioequivalence problem list, with information such as the drug product, applicant name, dosage form, and strength.[12] The Blue Book became an important guide to public and private procurement officers in determining which products to purchase.[13]

Simultaneously, states were developing their own lists, such as the New York State Department of Health’s formulary of Safe, Effective and Interchangeable Prescription Drugs (June 1977) and formulary of Safe, Effective and Therapeutically Equivalent Prescription Drugs (April 1978) (collectively known as the “Green Book”), which were updated quarterly and “certified or approved by [the] Commissioner of [the] Federal Food and Drug Administration.”[14] The Green Book was different in content and development from the Blue Book or today’s Orange Book—for example, because it listed drugs “used primarily outside of the institutional setting,” e.g., for military use, and involved input from groups such as the New York legislature, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and healthcare practitioners.[15] Due in part to the “the varying definitions and criteria among the individual [state] statutes for evaluating therapeutic equivalence” and “volume of potential inquiries about a large number of products from a large number of individuals,” including requests from New York, Illinois, and at least 17 other states and the District of Columbia to ratify their formulary lists,[16] FDA recognized that it could not serve the needs of each state on an individual basis. Rather, FDA determined that providing a single list based on common criteria would be preferable to evaluating drug products on the basis of differing definitions and criteria under various state laws.[17]

B. Initial FDA Development of the Current Drug List

On May 31, 1978, the FDA Commissioner sent a letter to officials of each state announcing FDA’s intent to provide a list of all prescription drug products approved by FDA for safety and effectiveness, along with therapeutic equivalence determinations for multisource prescription products.[18] On June 30, 1978, FDA published an interim version of that list, which included approved NDAs, PANDAs, and antibiotic Form 5s (a type of application requesting certification of a new antibiotic product—see, e.g., 21 C.F.R. 146.13 (1965)), for comment by state officials, agencies, and the public, with the expectation of publishing annual editions and quarterly supplements.[19]

On January 12, 1979, FDA published a proposed rule to amend its regulations at 21 C.F.R. 20.117 to “make available a list of all approved drug products, together with therapeutic evaluations of listed products that are available from more than one manufacturer (multisource).”[20] FDA’s “major considerations” for the proposal included: 1) educating patients and purchasers, prescribers, and dispensers of drug products; 2) cooperating with the states in protecting the health and welfare of their citizens; 3) facilitating the President’s program to control inflation, and “additional considerations,” including 4) cooperating with the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) draft legislation that would require the establishment by an appropriate state health agency of a formulary that would list equivalent drug products; 5) minimizing confusion over the legal status of certain drug products; 6) providing more complete information on drugs that are FDA-approved and considered to be therapeutically equivalent; 7) minimizing so-called “man‑in‑the‑plant” practice[21]; 8) expanding on the existing Blue Book; and 9) acting on a recommendation from the congressionally created Office of Technology Assessment’s Drug Bioequivalence Study Panel.[22]

FDA also explained its “concept and rationale” regarding therapeutic equivalence, including that such products should be pharmaceutical equivalents, bioequivalent, adequately labeled, and manufactured in compliance with current good manufacturing practice.[23]

At the time of the proposed rule, FDA intended to revise the list “on a quarterly basis during the first year,” after which “the frequency of revisions would be reevaluated.”[24] FDA simultaneously published the first draft “List”—often referred to as the Proposed Annual Edition—which included only currently marketed prescription drug products approved by FDA through NDAs and PANDAs under Section 505 of the FD&C Act and antibiotics approved under analogous applications known as Form 5s or Form 6s under section 507 of the FD&C Act.[25]

On October 31, 1980, FDA published the final rule, Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, amending 21 C.F.R. 20.117, and simultaneously published the first annual edition of Approved Prescription Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations.[26] Because it was published on Halloween, FDA chose an orange cover for the compilation, prompting its current colloquial name: the Orange Book. In the final rule, FDA decided to publish supplements at monthly intervals rather than quarterly.[27]

Four years later, on September 24, 1984, the Hatch–Waxman Act was signed into law.[28] The Hatch–Waxman Act amended Section 505 of the FD&C Act to, among other things: require FDA to “publish and make available to the public—(I) a list in alphabetical order of the official and proprietary name of each drug which has been approved for safety and effectiveness under [Section 505(c)] before the date of the enactment of this subsection; (II) the date of approval if the drug is approved after 1981 and the number of the application which was approved; and (III) whether in vitro or in vivo bioequivalence studies, or both such studies, are required for applications filed under this subsection which will refer to the drug published”; to include patent information submitted by NDA holders; and to publish an update to the list every 30 days.[29]

The Orange Book and its monthly Cumulative Supplements satisfy the Hatch–Waxman Act’s requirement that FDA make publicly available a list of approved drug products with monthly supplements.[30] The Annual Edition—in recent years, typically published every January—contains all changes from the previous year. Notably, the Orange Book does not currently include: 1) pre‑1938 drugs that are not the subject of an approved application; 2) pre‑1962 drug products subject to the DESI process for which the DESI proceeding is not yet complete; 3) approved drugs that discontinued marketing prior to 1987; 4) tentatively approved drugs; 5) marketed drug products that are not the subject of an approved NDA or ANDA (e.g., over-the-counter (OTC) monograph products, biologics license applications (BLAs) (see below, Section II.C.2), and marketed unapproved products); 6) certain products such as authorized generic drug products and re-labeled drug products marketed under an application already reflected in the Orange Book (these are not separately identified); and 7) certain medical gases.

The Orange Book is published and maintained by FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Office of Generic Drugs (OGD), Office of Generic Drug Policy (OGDP), Division of Orange Book Publication and Regulatory Assessment (DOBPRA).

C. Major Orange Book Developments

FDA has made numerous updates and improvements to the Orange Book in its 45-year history—many of which may not be apparent from simply perusing the most recent Annual Edition or Orange Book’s online database. Below, we summarize notable changes made in five areas to help practitioners better understand the timing and scope of such changes.

1. Publication Timing Changes and Other General Changes

FDA has shifted the publication date of the Orange Book Annual Edition several times. The Orange Book Annual Edition does not list its annual publication date, but it does note the date through which the volume is current. The 1st Annual Edition was published on October 31, 1980, and was current through August 31, 1980. The 2nd through 6th Annual Editions (1981–1985) were published in late October and were current (with their accompanying first supplements) through September 30 of that year. No Orange Book was published in 1986, as publication of the 7th Annual Edition was shifted to late February 1987 (current through January 31, 1987)—which for the first time aligned the edition number and last digit of the publication year (7th Annual Edition, 1987). In the 21st Annual Edition (2001), FDA began its current practice of typically publishing in mid-January, with the last digit of the edition number matching the publication year but one number higher than the last digit of the effective calendar year—i.e., the 45th Annual Edition (2025), published in early February 2025, and current through December 31, 2024.

The Orange Book was available in a paper copy starting with publication of the draft Proposed Edition Orange Book in 1979. FDA launched a significant technological update in 1997 with the searchable electronic Orange Book database, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/index.cfm.[31] In its current form, the website allows users to search for approved drugs by proprietary name, active ingredient, application number, applicant (company), dosage form, or route of administration, and the results can be downloaded into a spreadsheet that provides additional fields (including the marketing status, product number, therapeutic equivalence code, reference listed drug (RLD), reference standard (RS), and approval date). Users can also search for patent information by patent number or by viewing newly added or delisted patents. From the related Orange Book informational webpage, users can download Orange Book data files in compressed (*.zip) files comprising: 1) “Products.txt” (ingredient, dosage form, route of administration, trade name, applicant, strength, NDA number, product number, therapeutic equivalence code, approval date, RLD, RS, type (e.g., Rx), and applicant full name); 2) “Patent.txt” (application type (NDA or ANDA), NDA number, product number, patent number, patent expiration date, drug substance flag, drug product flag, patent use code, patent delist request flag, and patent submission date); and 3) “Exclusivity.txt” (application type, NDA number, product number, exclusivity code, and exclusivity date)[32]; and another webpage provides information on how to filter such data.[33] FDA launched an express app (with more limited search functionality) for iOS and Android on November 9, 2015, maintaining active support for the app through late 2024. Official “paper copies” of the Orange Book were discontinued in 2022, although electronic (PDF) versions remain available via the Orange Book informational webpage.[34]

The development of the Orange Book website allowed FDA to change the frequency with which it publishes patent and generic drug approval information. In 2005, FDA switched from publishing patent listings in a public docket to publishing them daily on the Orange Book website.[35] Also in 2005, FDA switched from publishing generic drug approvals only monthly in the Cumulative Supplement to publishing them daily on the Orange Book website.[36] Publication in the monthly Cumulative Supplement and monthly data file updates to the Orange Book website follow the daily updates. Twice each month, typically on a Monday, FDA updates additional information on the Orange Book website including new drug approvals, ownership changes, marketing status updates, exclusivities, and various types of changes to drug listing information (e.g., changes related to therapeutic equivalence codes, trade names, and RLD or RS designation, among others).[37]

In July 2022, FDA published a final guidance for industry, Orange Book: Questions and Answers, to assist interested parties (including prospective drug product applicants, drug product applicants, and approved application holders) in utilizing the Orange Book by providing answers to commonly asked questions.[38]

2. Overarching Content Changes

The content of the Orange Book has also evolved over the years, with different components added, removed, and modified in response to statutory changes and under its own authority. Although we cannot document every change, below we summarize several key changes.

The 1st Annual Edition (1980) included a Preface; the Drug Product List (now called the Prescription Drug Product List); indices for the trade names, approved drug products per application holder, and application holder abbreviations; and an Appendix of Prescription Drug Products Deemed Approved Pending Resolution of Safety or Effectiveness Issues (DESI Pending List). The 2nd Annual Edition (1981) included new appendices on dosage forms, routes of administration, and abbreviations, which the 4th Annual Edition (1983) revised as the Appendix on Uniform Terms.

The 6th Annual Edition (1985)—the first published after the enactment of the Hatch–Waxman Act—made four significant changes. First, it added an OTC Drug Product List (the “OTC List”) and a Drug Products Approved Under Section 505 of the Act by the Division of Blood and Blood Products List (now called the Drug Products with Approval under Section 505 of the FD&C Act Administered by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research List). As explained in its introduction, previous editions of the Orange Book excluded these Lists “because the main purpose of the publication was to provide information to states regarding FDA’s recommendation as to which generic prescription drug products were acceptable candidates for drug product selection.” However, with the passage of the Hatch–Waxman Act requiring an up-to-date list of all marketed drug products—including both OTC and prescription—that have been approved for safety and efficacy and for which new drug applications are required, FDA added these two new Lists.

Second, the 6th Annual Edition added a Patent and Exclusivity Information Addendum. Like the OTC List, the Patent and Exclusivity Information Addendum was included in compliance with the Hatch–Waxman Act to identify drugs qualifying for periods of exclusivity and to provide patent information concerning the listed drugs. Third, the 6th Annual Edition removed the DESI Addendum. Congress had amended the FD&C Act in 1962 to require that new drugs be shown safe and effective to obtain FDA approval and to require FDA to evaluate the effectiveness of the drugs FDA had approved only for safety between 1938 and 1962. The Orange Book included the DESI Pending List in the 1st through 5th Annual Editions (1980–1984), with different editions breaking out the DESI Pending List into different categories and the 4th and 5th Annual Editions (1983–1984) renaming the compilation the DESI Addendum for clarity. After the enactment of the Hatch–Waxman Act, the Orange Book removed the DESI Addendum in the 6th Annual Edition.

Fourth, the 6th Annual Edition began flagging products discontinued from marketing with an “∂” symbol. In the 7th Annual Edition (1987), the Orange Book eliminated the 6th Annual Edition’s “∂” designation for discontinued products to instead include a Discontinued Drug Product List (commonly referred to as the Discontinued Section), a cumulative list of approved drug products that have never been marketed, have been discontinued from marketing and that FDA has not determined were withdrawn from sale for safety or effectiveness reasons, are for military use, have had their approvals withdrawn for reasons other than safety or efficacy subsequent to being discontinued from marketing, or are approved drug products that are not in commercial distribution (e.g., in applications for export only).[39] The 7th through 16th Annual Editions (1987–1996) included a list of resolved (approved or denied) ANDA Suitability Petitions (see 21 C.F.R. 314.93). The 13th through 16th Annual Editions (1993–1996) included, “as notification to the reader,” a list of applicable official United States Pharmacopeia (USP) monograph title additions or changes where the USP monograph updated the dosage form (e.g., oral elixir to oral solution) and label modifications were necessary.

In 2020, the Orange Book made a substantive deletion in removing biologics information in response to a statutory change. As of March 23, 2010, an approved application for a biological product under Section 505 of the FD&C Act was deemed to be a license for the biological product under Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act.[40] FDA then identified each approved application for a biological product under the FD&C Act that was deemed to be a license (i.e., an approved BLA), removed them from the Orange Book, and added them to FDA’s Purple Book: Lists of Licensed Biological Products with Reference Product Exclusivity and Biosimilarity or Interchangeability Evaluations (the “Purple Book”) on March 23, 2020.[41] Where FDA had withdrawn approval of an application for a biological product, it removed the application from the Orange Book but did not transition the product to the Purple Book.[42]

Figure 1, below, summarizes these discussed statutory and Orange Book changes from the 1st Annual Edition (1980) through the 40th Annual Edition (2020) and today:

3. Adding Application & RLD/RS Information

Several key updates relate to the inclusion or use of application information. The 1st through 4th Annual Editions of the Orange Book (1980–1983) organized the “List” by the active ingredient name, further subdivided by the dosage form and route of administration (e.g., “Capsule; Oral”) and strength, and additionally included the application holder’s abbreviated name and the therapeutic equivalence evaluation (e.g., “AA”). In the 5th Annual Edition (1984), FDA for the first time added the “application number (FDA’s file number) under which the particular drug product was approved.” In the 6th Annual Edition (1985), FDA clarified by including “the application number and product number (FDA’s file numbers [e.g., Products 001, 002]) and approval dates.” Through the 29th Annual Edition (2009), all application numbers in the Orange Book began with “N”; in the 30th Annual Edition (2010), the Orange Book first clarified in the application number whether the drug was approved under an NDA (N######) or under an ANDA/PANDA (A######).

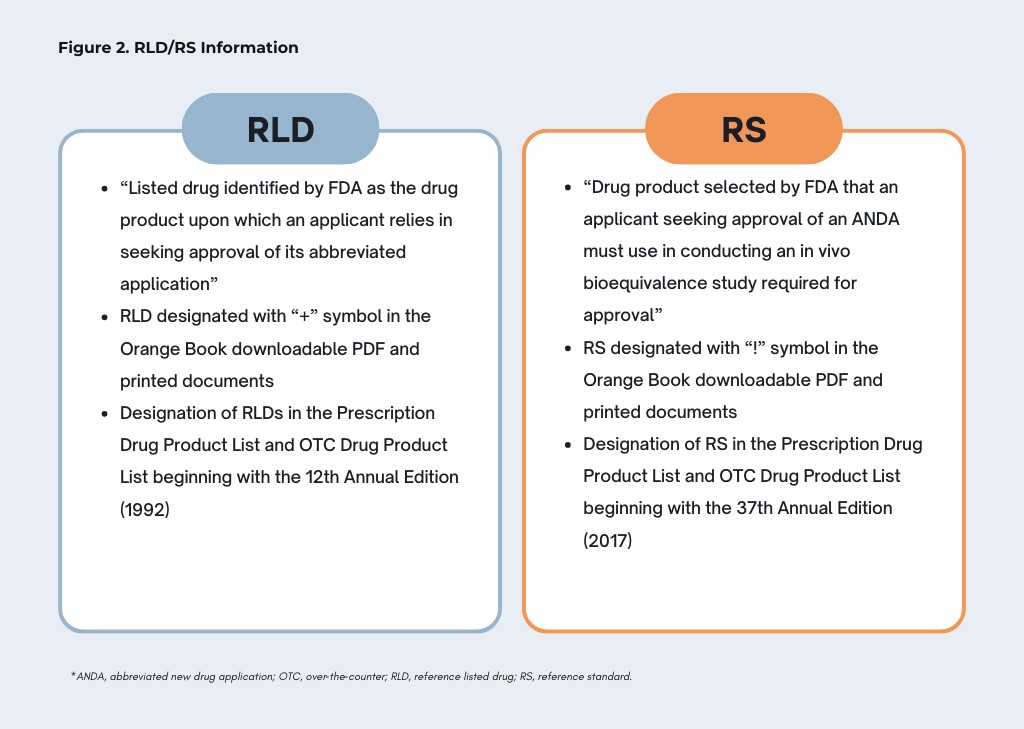

The Orange Book has also updated RLD and RS information. In the 1992 final rule implementing the Hatch–Waxman Act, FDA defined an RLD as “the listed drug identified by FDA as the drug product upon which an applicant relies in seeking approval of its abbreviated application.”[43] The 12th Annual Edition (1992) included this definition and began designating RLDs in the Prescription Drug Product List with a new “+” symbol, with RLD designations in the OTC Drug Product List following in the 13th Annual Edition (1993). As to RS, the 1992 final rule explained that an RS was the “drug product selected by the agency . . . for conducting bioequivalence testing.”[44] The RS was later defined in a 2016 final rule as the “drug product selected by FDA that an applicant seeking approval of an ANDA must use in conducting an in vivo bioequivalence study required for approval.”[45] In 1992, the Orange Book did not include a distinct symbol identifying the RS as distinct from the RLD; at its launch in 1997, the Orange Book website included a “yes” in the “RLD” column that signaled whether a product was either an RLD or RS. As explained in the 2016 final rule, the “+” and “yes” “resulted in confusion” and a need for further clarity as to RLD and RS.[46] As a result, in the 37th Annual Edition (2017), FDA began to modify the Prescription Drug Product and OTC Drug Product Lists in the Orange Book to clarify which listed drugs were RLDs and which were RSs and, on a forthcoming basis, to indicate which products in the Discontinued Section may be referred to as an RLD.[47] The printed version of the Orange Book began identifying each RLD with a “+” symbol and each RS with a “!” symbol; the Orange Book website included separate column headings for RLD and RS.[48]

Figure 2, below, briefly summarizes how RLD and RS are defined and when and how they began to be designated in the Orange Book:

4. Adding Patent & Marketing Exclusivity Information

The 1st Annual Edition did not contain any information about patents or exclusivities, with the Preface stating that “[i]f the application is approvable, the existence of a patent would not affect the agency’s decision to grant approval for marketing.” With the intervening passage of the Hatch–Waxman Act and other statutory changes, today the Orange Book contains a variety of information on patents and marketing exclusivities, with the 45th Annual Edition including almost 14,000 patents, almost 14,000 patent use codes (over 1,700 unique), and nearly 2,400 unique exclusivity codes.

Patents and Patent Use Codes

Following the enactment of the Hatch–Waxman Act, which required inclusion of certain patent information,[49] the 6th Annual Edition of the Orange Book (1985) included the first “Patent and Exclusivity Information Addendum” to identify patent information for listed drugs and drugs qualifying for exclusivity. This original Addendum included the NDA number, product number, patent number, patent expiration date, exclusivity code, and exclusivity expiration date. The 8th Annual Edition (1988) added the first patent use codes (or “U‑codes”)—25 of them—with the 45th Annual Edition expanding the number to 4,106. The Hatch–Waxman Act also included a provision by which ANDA applicants might certify that certain patents are “invalid or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of the new drug for which the application is submitted,” i.e., a “Paragraph IV” certification.[50] Reflecting this statutory change, the 8th Annual Edition (1988) for the first time included an exclusivity code for “patent challenge” (PC). PC refers to the 180‑day exclusivity available to the first generic applicant(s) to file a substantially complete ANDA containing a Paragraph IV certification to a patent listed in the Orange Book, where the first generic applicant(s) lawfully maintain(s) a Paragraph IV challenge to a patent listed in the Orange Book. The 24th Annual Edition (2004) was the first to include an indicator as to whether a listed patent contained drug substance (DS) and/or drug product (DP) claims. Since then, “DS” and “DP” indicators have been included based on information NDA holders submit to FDA on Form FDA 3542.

Although the Hatch–Waxman Act excluded antibiotic drug products—then‑approved under Section 507 of the FD&C Act—from its patent and marketing exclusivity provisions, the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA) amended the FD&C Act to deem “old” antibiotics approved or submitted for review before November 21, 1997, as approved under Sections 505(b) or 505(j).[51] Later, the QI Program Supplemental Funding Act of 2008 (QI Act) extended the Hatch–Waxman Act’s patent listing and certification provisions to old antibiotics, with FDA being required to publish certain patent information in the Orange Book by January 6, 2009.[52] FDA published the first “old antibiotic” patent listings to the Orange Book website on October 24, 2008.

In addition to the Annual Edition and monthly Cumulative Supplements, in 2005, FDA began publishing patent listings daily on the Orange Book website.[53] As part of FDA’s implementation[54] of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA),[55] FDA began consistently listing the patent submission date (the date on which FDA receives patent information from the NDA holder) for each newly listed patent on the Orange Book website in November 2017[56] and in the 38th Annual Edition (2018). Also in 2017, FDA added to the Orange Book website the Patent Listing Disputes List, which informs stakeholders which patents have been disputed by an outside party to FDA.[57]

We note that FDA serves a ministerial role with regard to patent listing, patent descriptions (i.e., DS, DP), and any method-of-use descriptions submitted by the NDA holder, meaning that although FDA reviews patent submissions for technical compliance to determine if all required information has been provided, it does not review the underlying patent to confirm or deny the appropriateness of the listing or the accuracy of the descriptions.[58]

Marketing Exclusivities

Regarding marketing exclusivities, the Hatch–Waxman Act included a five-year protection for applications for new active ingredients and a three-year protection for applications or supplements containing “reports of new clinical investigations (other than bioavailability studies) essential to the approval of the application [or supplement] and conducted or sponsored by the applicant.”[59] The 6th Annual Edition of the Orange Book (1985) first included 11 general shorthand descriptions of the nature of exclusivity-protected conditions or changes: “new combination” (NC), “new chemical entity” (NCE), “new dosage form” (NDF), “new ester or salt of an active ingredient” (NE), “new product” (NP), “new route” (NR), “parenteral in plastic container” (PP), “prescription to OTC status change” (RTO), “new strength” (NS), “new dosing schedule” (D), and “new indication” (I). D‑codes and I-codes—as well as later-added orphan drug exclusivity and patent use codes (see Figure 3 below)—are followed by a number, e.g., “D-1,” with each enumerated code having a specific definition. In the 6th Annual Edition, the Orange Book defined only 11 D-codes and 34 I-codes. By the 45th Annual Edition, this had expanded to 194 D‑codes and 956 I‑codes.

The 7th Annual Edition (1987) was the first to include a list of “Orphan Drug Products With Exclusive Approval” (listing the active ingredient(s), strength, trade name, dosage form, route of administration, applicant name, license number, approval date, and exclusivity expiration date), and that Edition’s Patent and Exclusivity Information Addendum also listed the “orphan drug exclusivity” (ODE) code for the first time. In the 38th Annual Edition (2018), FDA updated the Orange Book to include “individual descriptions of the protected use,” i.e., which indication(s) are protected by orphan drug exclusivity, with the ODE code followed by a number correlated with a specific definition, similar to D‑codes and I‑codes. FDA added a related code, “ODE*”—first in the March 2021 Cumulative Supplement and then in the 42nd Annual Edition (2022)—to note that the timing of approval of certain follow-on applications may be subject to delay due to ODE for another drug that has the same active moiety.

After the enactment of FDAMA’s voluntary incentives for pediatric studies (later superseded by and codified in the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) and the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA)[60]), FDA updated the Orange Book in the 19th Annual Edition (1999) to first separate the six‑month pediatric exclusivity extension from the underlying exclusivity code, resulting in a new “Pediatric Exclusivity” (PED) code. The 20th Annual Edition (2000) added the first three‑year exclusivity “miscellaneous” code (M-code), which, like I‑codes, D‑codes, and ODE‑codes, is followed by a number with a specific definition; by the 45th Annual Edition, the Orange Book listed 312 unique M‑codes.

The September 27, 2007 Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA) contained a provision permitting NCE exclusivity for certain single enantiomers contained in an approved racemic drug.[61] FDA published the first such exclusivity in the July 2013 Cumulative Supplement and subsequently in the 34th Annual Edition (2014) added a description of the code “NCE*,” meaning “new chemical entity (an enantiomer of previously approved racemic mixture)” and citing to Section 505(u) of the FD&C Act. After the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 (FDASIA) created a new five‑year “generating antibiotic incentives now” (GAIN) marketing exclusivity for certain new antibacterial and antifungal drugs under Section 505E of the FD&C Act,[62] the May 2014 Cumulative Supplement and the 35th Annual Edition (2015) were the first to include the “GAIN” exclusivity code. After the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (FDARA) created a pathway by which FDA may, at the request of the applicant, designate a drug with “inadequate generic competition” as a “competitive generic therapy” (CGT),[63] and by which drugs so designated may qualify for a 180-day exclusivity period, the 38th Annual Edition (2018) added code “CGT” to identify the ANDAs eligible for CGT exclusivity.

Figure 3, below, summarizes these changes in the Orange Book’s content for listing patent and exclusivity information, with patent information summarized on the top half of the timeline and marketing exclusivity information summarized on the bottom half:

5. Drug Product Listing Changes

As needed, FDA may individually update drug product listings to reflect up-to-date and accurate information. But more broadly, the Orange Book has made several changes throughout its history that affect the drug product listings of certain categories of drug products.

Since the 1st Annual Edition, FDA has updated certain drug product listing terminology to increase clarity. For example, in the 1st Annual Edition, the “Drug Product Examples” in the Preface list the dosage form and route of administration as “Injectable; Injection.” Likewise, in the 4th Annual Edition’s (1983) Appendix E of “Uniform Terms,” the Orange Book included “Injectable” as a dosage form and “Injection” as a route of administration. This was consistent with FDA’s 1979 proposed rulemaking for the Orange Book that noted, for “[a]queous injectable (parenteral) solutions,” that “[a]ll injectable products are listed under the general category ‘Injectable; Injection’ but specific routes of administration are not shown.”[64] Over the years, however, the Orange Book’s Uniform Terms list of dosage forms and routes of administration expanded, with the 45th Annual Edition listing 85 dosage forms and 47 routes of administration. From 2002–2003, FDA began prospectively describing new NDA and first ANDA approvals with more specific dosage forms and routes of administration (e.g., “solution” and “intravenous”). For already approved products listed as “Injectable; Injection,” the Orange Book typically retained that dosage form and route of administration description for the RLD product, existing ANDA approvals, and future ANDA approvals referencing that RLD. Beginning in 2018, the Orange Book began updating “IV (infusion)” drug product listings to simply list “Intravenous” as the route of administration, and by the 45th Annual Edition (2025) no “IV (infusion)” descriptors remained.

Another category of drug product listing terminology updates occurred in 2003. Prior to the 23rd Annual Edition, the Orange Book had listed the “strength” of most liquid parenteral drug products by concentration without displaying the complete strength information (i.e., concentration and total drug content); for dry powder or freeze-dried powder in a container, the strength was listed as the amount of drug in the container. However, for purposes of Section 505(j)(2)(A)(iii) of the FD&C Act, FDA had a “longstanding history” of considering a difference in the total quantity of drug substance of a parenteral product (e.g., a single- or multiple-dose vial) or a difference in the concentration of a parenteral product to be a difference in the “strength.”[65] Accordingly, beginning in the 23rd Annual Edition (2003), the strength information in the Orange Book for new parenteral drug products began prospectively including both the total drug content and concentration. As a result, for an NDA or ANDA covering products with different total drug contents but the same concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL, 5 mg/5 mL, 10 mg/10 mL) or the same total drug content across multiple concentrations (e.g., 1 mg/mL, 1 mg/10 mL, 1 mg/100 mL), each product with a different total drug content and/or concentration has its own drug product listing in the Orange Book.

III. Conclusion

The Orange Book has been and continues to be a living document that has reflected numerous updates and changes throughout its 45-year history. Given the volume of information contained in the Orange Book, some changes have been applied prospectively only, resulting in a mixture of practices and conventions in the publication. Historically, these changes have occurred at different times throughout the Orange Book’s tenure and have generally been based on various changes in the statutory and regulatory framework governing the drug review and approval process as it relates to the information provided in the Orange Book. By summarizing the major changes in the Orange Book since its first publication and providing historical context for when or why certain changes occurred, Orange Book users now have this consolidated resource with additional detailed information to deepen their understanding and improve their use of this important publication.

[1] Food and Drugs Act of 1906 (Pure Food and Drug Act), Pub. L. 59–384, 34 Stat. 768 (1907); 21 C.F.R. Part 310—Conditions for Marketing Human Prescription Drugs: Proposed Rule Making and Notice of Enforcement Policy for Drugs Subject to the Effectiveness Requirements of the Drug Amendments of 1962, Docket No. 75N–0052, 40 Fed. Reg. 26142, 26142–56 (proposed June 20, 1975).

[2] Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), Pub. L. 75–717, 52 Stat. 1040, 1040–59 (1938).

[3] Drug Amendments of 1962 (Kefauver–Harris Drug Amendments), Pub. L. 87–‑781, 76 Stat. 780, 789–96 (1962).

[4] 21 C.F.R. Part 130—New Drugs: Abbreviated Applications, 34 Fed. Reg. 2673, 2673 (Feb. 27, 1969); FDA, Pre-Hatch-Waxman Abbreviated New Drug Applications in the Prescription Drug Product List (July 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/151443/download.

[5] 21 C.F.R. Part 130—New Drugs: Abbreviated Applications, 34 Fed. Reg. 2673, 2673 (Feb. 27, 1969); Subchapter C—Drugs, Part 130—New Drugs, Abbreviated Applications, 35 Fed. Reg. 6574–75 (Apr. 24, 1970); Drug Products Approved in Abbreviated New Drug Applications Before the Enactment of the Hatch–Waxman Amendments; Establishment of a Public Docket; Request for Comments, 86 Fed. Reg. 44731, 44731–36, Docket No. FDA–2020–N–1245 (Aug. 13, 2021).

[6] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch–Waxman Act), Pub. L. 98–417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984).

[7] Federal Trade Commission—Public Workshop: Follow On Biologics: Impact of Recent Legislative and Regulatory Naming Proposals on Competition, 78 Fed. Reg. 68840, 68843 (Nov. 15, 2013).

[8] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Approved Prescription Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the Orange Book) (45th Annual Ed., 2025), Preface, at iv.

[9] Procedures for Establishing a Bioequivalence Requirement: Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Docket No. 75N–00500, 40 Fed. Reg. 26164, 26168 (proposed June 20, 1975).

[10] List of Firms Approved to Market Drug Products Having Known or Potential Bioequivalence Problems: Notice of Availability, 41 Fed. Reg. 5339, 5339 (Feb. 5, 1976).

[11] Id.

[12] Id. at 5349–40; Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2932–53 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979).

[13] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2935 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979); Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), Holders of Approved New Drug Applications for Drugs Presenting Actual or Potential Bioequivalence Problems, HEW Publication No. 76-3009 (Revised, June 1976).

[14] N.Y. State Dep’t of Health, Safe, Effective, and Therapeutically Equivalent Prescription Drugs (Apr. 1, 1978) (the Green Book), at iii–iv.

[15] Id. at iv.

[16] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2934–35 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979).

[17] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2932–53 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979); Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), Holders of Approved New Drug Applications for Drugs Presenting Actual or Potential Bioequivalence Problems, HEW Publication No. 76-3009 (Revised, June 1976); Orange Book (Proposed Annual Ed., 1979).

[18] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Approved Prescription Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the Orange Book) (45th Annual Ed., 2025); Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2934 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979); Orange Book (Proposed Annual Ed., 1979), Preface, at 2.

[19] Approved Drug Products: Availability of an Interim List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 43 Fed. Reg. 28557, 28557 (June 30, 1978); Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2952 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979)

[20] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2932 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979).

[21] Under “man‑in‑the‑plant” practice, a first drug manufacturer (Company A) would contact a second drug manufacturer (Company B)—typically the maker of a competing brand or generic product—to manufacture Company A’s drug product. Company A would send a “man‑in‑the‑plant” to Company B to assure the manufactured product met Company A’s standards, and the resulting product’s labeling would reflect Company A as the manufacturer. Congressional investigations found the practice deceptive to consumers by misleading purchasers as to the identity of the actual manufacturer of a drug product.

[22] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2932–36 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979).

[23] Id. at 2937–48.

[24] Id. at 2953.

[25] Orange Book (Proposed Annual Ed., 1979), Preface, at 3.

[26] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs; Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 45 Fed. Reg. 72582, 72607–08 (Oct. 31, 1980) (effective Dec. 1, 1980).

[27] Id.

[28] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch Waxman Act), Pub. L. 98–417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984).

[29] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch Waxman Act), Pub. L. 98–417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984).

[30] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Approved Prescription Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the Orange Book) (45th Annual Ed., 2025), Preface, at v.

[31] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., From Our Perspective: The Orange Book at 40: A Valued FDA Resource Continually Enhanced by User Input (Oct. 26, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/our-perspective/our-perspective-orange-book-40-valued-fda-resource-continually-enhanced-user-input (last visited May 12, 2025).

[32] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Orange Book Data Files (Feb. 14, 2025), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/orange-book-data-files (last visited May 12, 2025).

[33] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Orange Book Data File Download Instructions, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/ob/OrangeBookDataFileDownloadInstructions.pdf (last visited May 12, 2025).

[34] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Frequently Asked Questions on The Orange Book (Jan. 15, 2025), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/frequently-asked-questions-orange-book (last visited May 12, 2025).

[35] Id.; Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the “Orange Book”); Establishment of a Public Docket; Request for Comments, Docket No. FDA–2020–N–1069, 85 Fed. Reg. 33165, 33167 (June 1, 2020).

[36] Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the “Orange Book”); Establishment of a Public Docket; Request for Comments, Docket No. FDA–2020–N–1069, 85 Fed. Reg. 33165, 33167 (June 1, 2020).

[37] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Orange Book: Questions and Answers, Guidance for Industry (July 2022), at 5 (A3).

[38] Id.

[39] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Approved Prescription Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the Orange Book) (45th Annual Ed., 2025), Preface, at xxiv and 2-2.

[40] Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Title VII, Subtitle A: Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009, Pub. L. 111–148, 124 Stat. 804 (2010).

[41] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., List of Approved NDAs for Biological Products That Were Deemed to be BLAs on March 23, 2020 (Mar. 23, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/media/119229/download (last visited May 12, 2025) (available from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book).

[42] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., List of Withdrawn Applications for Biological Products That Were Removed From FDA’s Orange Book on March 23, 2020 (Mar. 23, 2020), https://www.fda.gov/media/136420/download (last visited May 12, 2025) (available from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book).

[43] Abbreviated New Drug Application Regulations, Docket No. 85N–0214, 57 Fed. Reg. 17950, 17982 (Apr. 28, 1992) (final rule).

[44] Id. at 17985.

[45] Abbreviated New Drug Applications and 505(b)(2) Applications, FDA–2011–N–0830, 81 Fed. Reg. 69580, 69638 (Oct. 6, 2016) (final rule).

[46] Id. at 69619; see also U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Referencing Approved Drug Products in ANDA Submissions, Guidance for Industry (Oct. 2020), at 11 .

[47] Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the “Orange Book”); Establishment of a Public Docket; Request for Comments, Docket No. FDA–2020–N–1069, 85 Fed. Reg. 33165, 33167 (June 1, 2020); U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Referencing Approved Drug Products in ANDA Submissions, Guidance for Industry (Oct. 2020), at 10–11.

[48] U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Referencing Approved Drug Products in ANDA Submissions, Guidance for Industry (Oct. 2020), at 10.

[49] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch Waxman Act), Pub. L. 98–417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984).

[50] Id.

[51] Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA), Pub. L. 105–115, 111 Stat. 2296, 2296–2380 (1997).

[52] QI Program Supplemental Funding Act of 2008 (QI Act), Pub. L. 110–379, 122 Stat. 4075, 4075–79 (2008).

[53] Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the “Orange Book”); Establishment of a Public Docket; Request for Comments, Docket No. FDA–2020–N–1069, 85 Fed. Reg. 33165, 33165–67 (June 1, 2020).

[54] Abbreviated New Drug Applications and 505(b)(2) Applications, FDA–2011–N–0830, 81 Fed. Reg. 69580, 69580–658 (Oct. 6, 2016) (final rule).

[55] Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA), Pub. L. 108–173, 117 Stat. 2066, 2066–2480 (2003).

[56] Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the “Orange Book”); Establishment of a Public Docket; Request for Comments, Docket No. FDA–2020–N–1069, 85 Fed. Reg. 33165, 33167 (June 1, 2020).

[57] Id.; U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations | Orange Book – Orange Book Patent Listing Dispute List (last visited May 12, 2025), current edition available from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/approved-drug-products-therapeutic-equivalence-evaluations-orange-book.

[58] Applications for FDA Approval to Market a New Drug: Patent Submission and Listing Requirements and Application of 30 Month Stays on Approval of Abbreviated New Drug Applications Certifying That a Patent Claiming a Drug Is Invalid or Will Not Be Infringed, Docket No. 02N–0417, 68 Fed. Reg. 36676, 33676–712 (June 18, 2003) (final rule); U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Dear Applicant Letter from FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research to Hospira Inc re Dexmedetomidine Hydrochloride Injection, Docket No. FDA–2014–N–0087 (Jan. 15, 2014).

[59] Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Hatch Waxman Act), Pub. L. 98–417, 98 Stat. 1585 (1984).

[60] Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA), Pub. L. 105–115, 111 Stat. 2296, 2296–2380 (1997); U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Pediatric Drug Development: Regulatory Considerations—Complying With the Pediatric Research Equity Act and Qualifying for Pediatric Exclusivity Under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, Draft Guidance for Industry (May 2023, Rev. 1); Best Practices for Children Act (BPCA), Pub. L. 107–109, 115 Stat. 1408, 1408–24 (2002); Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 (PREA), Pub. L. 108–155, 117 Stat. 1936, 1936–43 (2003).

[61] Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA), Pub. L. 110–85, 121 Stat. 823, 823–978 (2007).

[62] Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA), Pub. L. 112–144, 126 Stat. 993, 993–1132 (2012).

[63] FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (FDARA), Pub. L. 115–52, 131 Stat. 1005, 1005–90 (2017).

[64] Therapeutically Equivalent Drugs: Availability of List, Docket No. 78N–0170, 44 Fed. Reg. 2932, 2950 (proposed, Jan. 12, 1979).

[65] Abbreviated New Drug Applications and 505(b)(2) Applications, Docket No. FDA–2011–N–0830, 80 Fed. Reg. 6802, 6816 (proposed Feb. 6, 2015).

FDLI is a nonprofit membership organization that offers education, training, publications, and professional networking opportunities in the field of food and drug law. As a neutral convener, FDLI provides a venue for stakeholders to inform innovative public policy, law, and regulation. Articles and any other material published in Update represent the opinions of the author(s) and should not be construed to reflect the opinions of FDLI, its staff, or its members. The factual accuracy of all statements in the articles and other materials is the sole responsibility of the authors.

Crystal Canterbury, J.D., is a Regulatory Counsel in FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy, Division of Legal and Regulatory Support, where she works to resolve complex bioequivalence, labeling, patent certification, and other regulatory issues to enable generic drug approvals. Prior to joining FDA in 2020, Crystal spent nearly a decade as a litigator with two large Washington, D.C., law firms where she represented generic pharmaceutical clients in Hatch-Waxman patent litigation and proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.

Crystal Canterbury, J.D., is a Regulatory Counsel in FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy, Division of Legal and Regulatory Support, where she works to resolve complex bioequivalence, labeling, patent certification, and other regulatory issues to enable generic drug approvals. Prior to joining FDA in 2020, Crystal spent nearly a decade as a litigator with two large Washington, D.C., law firms where she represented generic pharmaceutical clients in Hatch-Waxman patent litigation and proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.  Katelyn Nguyen, Pharm.D., is a Pharmacist in FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy, Division of Orange Book Publication and Regulatory Assessment, where she analyzes information related to FDA-approved drug applications, including marketing protections related to patents and exclusivity, and ensures the information about these drug applications in the publication Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (commonly known as the Orange Book) is accurate and up-to-date. Prior to joining FDA, Katelyn worked as an inpatient pharmacist for a DOD and VA hospital where she provided medication therapy management, patient education, and drug information to current and retired servicemen and women.

Katelyn Nguyen, Pharm.D., is a Pharmacist in FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy, Division of Orange Book Publication and Regulatory Assessment, where she analyzes information related to FDA-approved drug applications, including marketing protections related to patents and exclusivity, and ensures the information about these drug applications in the publication Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (commonly known as the Orange Book) is accurate and up-to-date. Prior to joining FDA, Katelyn worked as an inpatient pharmacist for a DOD and VA hospital where she provided medication therapy management, patient education, and drug information to current and retired servicemen and women. Andrew Coogan, Pharm.D., MPH, is a Lieutenant Commander in the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service and a Regulatory Officer within FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy, Division of Legal and Regulatory Support, Patent and Exclusivity Team, where he helps expedite the review of public health priority submissions, including for drug shortages, evaluates generic drug applications to ensure compliance with statutory requirements related to patents and exclusivities and determines their eligibility for FDA approval based on patent and/or exclusivity protections. Andrew joined FDA in 2014 as a Regulatory Project Manager and has worked in FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy since 2018.

Andrew Coogan, Pharm.D., MPH, is a Lieutenant Commander in the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service and a Regulatory Officer within FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy, Division of Legal and Regulatory Support, Patent and Exclusivity Team, where he helps expedite the review of public health priority submissions, including for drug shortages, evaluates generic drug applications to ensure compliance with statutory requirements related to patents and exclusivities and determines their eligibility for FDA approval based on patent and/or exclusivity protections. Andrew joined FDA in 2014 as a Regulatory Project Manager and has worked in FDA’s Office of Generic Drug Policy since 2018.