CRN & NAD Reflect on the CRN-NAD Advertising Review Program

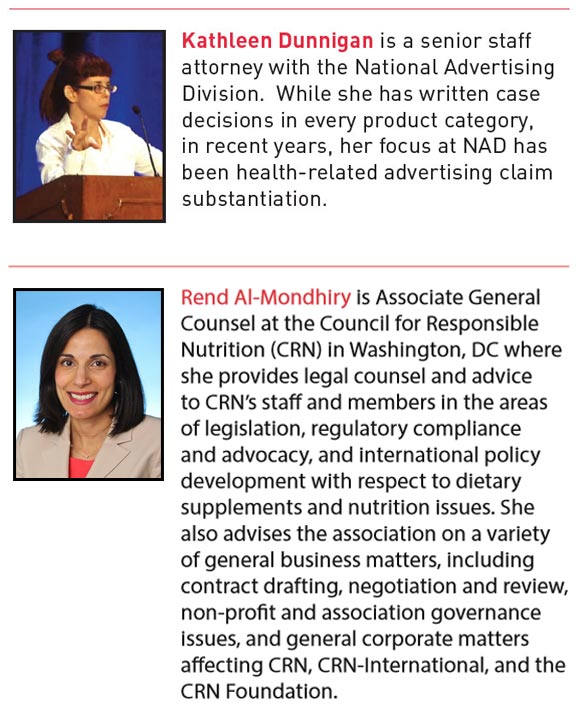

by Kathleen Dunnigan and Rend Al-Mondhiry

It’s a common scenario among many industries: company #1 is doing the right thing and marketing its products in compliance with the law. Along comes company #2, making outrageous claims and promising the next miracle product with claims such as “LOSE 5 LBS IN ONE WEEK—with no diet or exercise!” or “Improve your memory in just 10 days!” Ten years ago, this scenario was the norm for the dietary supplement industry. Compliant companies often found themselves competing with off-the-wall claims, with consumers left to sort out fact from fiction on their own. In 2006, the Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN), a trade association representing the dietary supplement and functional food industry began searching for a way to protect both consumers and the industry’s reputation from this small but persistent segment of the industry that clearly had no regard for the law.

The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) truth-in-advertising law can be summed up by two simple statements: 1) advertising must be truthful and not misleading and 2) before disseminating an ad, advertisers must have adequate substantiation for all product claims. For claims about the efficacy and safety of foods, including dietary supplements, FTC requires substantiation in the form of competent and reliable scientific evidence. However, federal agencies such as FTC have limited resources and cannot police every ad in the marketplace. With the help of the National Advertising Division (NAD), a leader in industry self-regulation, CRN saw an opportunity to help clean up the industry and make a difference.

History of the CRN-NAD Program

Ten years ago, CRN approached NAD with a novel idea: create a program to increase monitoring of the dietary supplement advertising, restore consumer confidence, and level the playing field so all companies play by the same rules. An already established, well-regarded self-regulatory forum with a solid reputation as a fair and transparent decision-maker, NAD was the natural choice.

As part of its agreement with CRN, NAD committed to reviewing 20 cases each year through its own monitoring efforts, while CRN agreed to bring 10 cases per year as the challenger in such cases. When reviewing dietary supplement advertising, NAD has a history of case decision and established precedent. FTC’s Dietary Supplement Advertising Guide also serves as the primary guide for reviewing an advertiser’s substantiation.

Why Self-Regulation? And Why NAD?

Effective enforcement of advertising laws can come from both government regulation and self-regulation. Self-regulation is a great option because it saves money, time, and the hassle of bringing your grievances in court or waiting for the federal government to take action. FTC Chairwoman Edith Ramirez recently praised the CRN-NAD program as an example of “how impactful self-regulation can be,” further noting that “the program has been a valuable complement to the FTC’s own enforcement efforts to eliminate fraud in this industry.”1

NAD is also a forum where competitors can bring challenges, rather than pursuing a Lanham Act claim which, for many reasons, is often not tenable due to the expense, publicity, and the length of time to bring such cases to conclusion. NAD also has tremendous experience and a robust archive of case precedent.

What’s Ahead for CRN and NAD

Flash forward to 2016: ten years and 270+ cases later, the CRN-NAD program is still going strong. CRN, through its CRN Foundation, has committed over $2 million to the program to help ensure its viability. And, although this program will not replace the work of FTC, as noted above by the Commission this program is a viable alternative that complements the work of law enforcement and puts companies on notice that another set of eyes is monitoring advertising claims. Without a doubt, CRN will continue its commitment for another ten years and beyond to ensure that the dietary supplement marketplace does not leave the industry cringing and consumers confused or duped by deceptive claims. So for all the company #1s out there, it’s the perfect place to take on those wild claims you see pop up in your email or on late night TV. For all the company #2s out there in the dietary supplement industry, watch out because the CRN-NAD program is here to stay.

NAD Reflects on a Few Substantive Substantiation Lessons from 10+ Years of Dietary Supplement Advertising Review

Whether the claims appear on paper, in pixels, or are riding the FCC airwaves, funding from the CRN Foundation has allowed NAD to expand its monitoring of dietary supplement advertising. NAD is privileged to be entrusted with the resources to review claim substantiation on important and meaningful issues such as health-related advertising, the category that comprises the vast majority of our supplement and functional food cases. NAD would like to think that there have been some evidentiary lessons learned along our ten-year way, especially when grappling with the nuances of what constitutes competent and reliable scientific evidence.

We all agree that “competent and reliable scientific evidence” is the right name for the level of substantiation required to support health-related claims. Resources abound that might possibly sort of maybe tell us what that actually means. FTC guidance describes competent and reliable scientific evidence as “tests, analyses, research, studies, or other evidence based on the expertise of professionals in the relevant area that have been conducted and evaluated in an objective manner by persons qualified to do so, using procedures generally accepted in the profession to yield accurate and reliable results.” (FTC, Dietary Supplements: An Advertising Guide to Industry). FDA has spoken with a fair amount of specificity on the hallmarks of sound clinical trial methodology, quality and type of evidence, expert opinions, and relevance of a study to the advertiser’s claim. (Guidance for Industry: Substantiation for Dietary Supplement Claims Made Under Section 403(r) (6) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act). NAD case decisions in the past several years regarding dietary supplement advertising almost uniformly cite to FDA and FTC guidance on the evidentiary value of the various scientific data that flows through NAD’s doors.

The concept of competent and reliable scientific evidence as applied to real life advertising claims does get murky when comparing court decisions as well as regulatory and self-regulatory guidance. For example, some federal courts, including a circuit court, have defined competent and reliable scientific evidence (at least for claims that causally link supplementation to health outcomes) as randomized, placebo-controlled human clinical trials; however, cases coming out of other lower courts arguably point to a less rigorous, more flexible definition. More of these same types of deliberations can be found in published Statements from FTC Commissioners who sometimes put fingers to keyboards when they disagree with one another about evidence and whether to enter into a Consent Order enjoining an advertiser from making particular health claims—which, while more work for them, is fortunate for us because we can gain insight into the ongoing tensions of creating a clearer, more comprehensive understanding of what kinds of tests, analysis and studies constitute competent and reliable scientific evidence that balances certainty with providing more information, rather than less, to the public.

Then again, maybe all this back and forth doesn’t point to disagreement about standards as much as that claim substantiation hinges on the sights and sounds—the overall experience—of the challenged advertising. (And who knows, maybe future advertising will engage more of our senses. The smell of warm cookies or fresh laundry could get most anyone to buy most anything). One of the largest repositories of the analysis of the messages conveyed by the words, music, and the pretty pictures of past and present marketing campaigns, in the context of the competent and reliable standard, is NAD’s archive of case decisions (270+ dietary supplement cases, and over 6000 cases of all stripes, dating back to 1971). It is a searchable database for practitioners seeking to determine whether particular advertising claims are a good fit for the support provided.

For example, many cases in our archives expound on how to better use expert scientists. Better uses of scientists may include using their expertise to provide an overview of the body of evidence of a dietary ingredient’s effect on human health. The best of these overviews reference supporting documentation—like clinical trials conducted on the ingredient—and, if applicable, help to reconcile outlying data. Expert scientist opinions, coupled with the appropriate documentation, are also excellent resources for providing context as to why one trial methodology may yield more accurate results, assurances that compound ingredients do not interfere with efficacy of any one particular ingredient, or why results may be appropriately extrapolated from a study population to the population to whom the advertising is targeted. Expert reports that shy away from unfavorable data tend to raise more questions than they answer. Also less valuable as evidence of efficacy are expert opinions that describe, without more, the expert’s favorable view of a product. Generally, consensus by experts in the field carries more evidentiary weight than the personal views of one scientist.

Another concern that has arisen in several cases is where evidence for health-related claims involves a syllogistic leap. A sample argument goes something like this: cell oxidation is present in greater amounts in people with certain health conditions; supplementation with a dietary ingredient raises antioxidant levels and lowers oxidation; therefore, taking this ingredient will protect your health or even help prevent disease. Assuming the first two statements are supported, the final conclusion—that taking this supplement will protect your health—may seem self-evident. However, this untested conclusion, without more, does not demonstrate that consumers will likely achieve the promised benefit, and, as a result, runs the risk of falling short of the competent and reliable standard. Evidence that more closely matches the claim will be more appropriate, such as, testing that demonstrates that the ingredient improved a well-accepted biomarker of a health parameter. Alternatively, the advertising itself could be revised.

These examples were selected with the criteria that they were interesting and not necessarily obvious. More common claim substantiation controversies include the fact that honest testimonials from happy customers (including celebrities on Instagram!) are not competent and reliable evidence; ingredient studies offered as claim substantiation should have the same dosage, formulation and route of administration as the ingredients in the products they purport to support; and advertisers bear the burden for establishing a reasonable basis for their claims. NAD also knows that you know that while we do not sort advertising into “disease” or “structure-function” regulatory categories, if you think that your claim is a structure-function claim, it still needs the level of evidentiary support appropriate to the reasonably conveyed advertising messages.

- Stephen Daniells, NutraIngredients, ‘Impactful meaningful self-regulation’: CRN & NAD celebrate 10 years of advertising program June 28, 2016, http://mobile.nutraingredients-usa.com/Regulation/Impactful-meaningful-self-regulation-CRN-NAD-celebrate-10-years-of-advertising-program.

Update Magazine

November/December 2016