Strengthening the Regulation of Dietary Supplements—Lessons from Prevagen®

By William J. Degnan, Leila Barraza, Leslie V. Farland, Yann C. Klimentidis & Elizabeth T. Jacobs

Introduction

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for regulating the dietary supplement market, whose U.S. market size was $46 billion in 2020. Dietary supplements that claim to improve memory are among the most popular, especially within the country’s aging population. Prevagen® (“Prevagen”) is one of several brands that claim to improve memory and provide other cognitive benefits. The maker of Prevagen, Quincy Bioscience, LLC (“Quincy”), settled a class action lawsuit in 2020 with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) charging it with deceptive business practices and false advertising related to Prevagen. The settlement allows Quincy Bioscience to continue marketing Prevagen provided it qualifies its advertising claims with a court-approved disclaimer. The disclaimer Quincy now uses for Prevagen, “based on a clinical study of subgroups of individuals who were cognitively normal or mildly impaired,” has a technical meaning not likely understood by the typical dietary supplement consumer. Quincy identified these clinical subgroups in an unplanned post hoc analysis performed after it failed to find a statistically significant treatment effect for Prevagen versus placebo in a study population as a whole. Most critically, Quincy’s claim of Prevagen’s statistically significant efficacy in certain patient subgroups is unreliable given that the analysis was not adjusted for multiple testing in accordance with good statistical practice. Congress can protect the public’s health from future legal settlements like Quincy v. FTC by revising U.S. dietary supplement regulations to require manufacturers provide strong, preapproved scientific evidence to substantiate the marketing claims for their products.

Dietary Supplement Regulation

Commenting in September 2020 on the current state of dietary supplement regulation in the U.S., Steven Tave, Director of the Office of Dietary Supplement Programs (ODSP) at FDA, stated, “[F]rom a public health perspective . . . there is one thing even more dangerous than a poorly regulated market, and that thing is a poorly regulated market that the public wrongly believes to be well regulated.”[1]

That regulation, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA),[2] is in urgent need of revision as evidenced by court cases surrounding Quincy’s marketing of Prevagen. According to court documents, between 2007 and 2020 Quincy profited from untruthful and misleading advertising claiming Prevagen improves memory and cognitive function in healthy users within 90 days.[3] In 2012, FDA sent Quincy a warning letter citing it for failure to report adverse events and product complaints associated with Prevagen.[4] The letter also stated that Prevagen was an unapproved new drug and did not qualify as a dietary supplement. Quincy’s deceptive marketing of Prevagen has resulted in several class action complaints, first by Racies v.Quincy in January 2015 and last by Collins v. Quincy in July 2019.[5] A complaint for permanent injunction and other equitable relief was brought by the FTC and the state of New York in January 2017.[6] These legal actions can be largely attributed to the FDA’s current reactive approach to regulating the U.S. dietary supplement industry.[7]

Quincy Bioscience and Prevagen

Quincy Bioscience, LLC was founded in Madison, Wisconsin in June 2004. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company, Inc. and its subsidiaries manufacture and sell Prevagen, which contains synthetically produced apoaequorin, its only active ingredient.[8] Apoaequorin is a calcium-binding protein found in Aequorea victoria, a species of jellyfish native to the Pacific Northwest.[9] In 2017, users paid between $24 and $70 for a 30-day supply of Prevagen, depending on the formulation and seller.[10]

Prevagen is a dietary supplement and nootropic. Nootropics are drugs, dietary supplements, and other substances that claim to improve cognitive function in healthy persons. These claims include memory, creativity, attention, and intelligence improvement.[11] As a nootropic, Quincy’s labelling promotes Prevagen as clinically shown to reduce memory problems associated with aging and improve memory within 90 days,[12] supports “healthy brain function,” a “sharper mind,” and “clearer thinking.” Quincy’s website in 2015 stated that during the aging process, human brains experience a loss of proteins needed for healthy function, thus “leaving brain cells vulnerable to damage,”[13] and that “Prevagen helps support brain cells by supplementing the [lost] proteins with the patented ingredient apoaequorin.”[14] Furthermore, Quincy’s website claimed that apoaequorin is capable of crossing the blood-brain and gastrointestinal barriers and thus enters the brain via the nervous and circulatory systems.[15]

The Case Against Prevagen

Despite advertising claims, there is no reliable scientific evidence that supports Quincy’s declarations of Prevagen’s efficacy.

Quincy relies on the calcium-binding property of apoaequorin to support its claim of efficacy in age-related memory loss and overall mental decline during normal brain aging.[16] However, given that apoaequorin is a protein, its bioavailability to the brain is likely nonexistent. According to unpublished in vitro data, when subjected to the pepsin enzyme produced in the stomach, the “apoaequorin protein is digested or enzymatically hydrolyzed to amino acids that are likely to be absorbed in the digestive tract.”[17] Therefore, like other dietary proteins, apoaequorin is rapidly broken down chemically and will not reach and enter the brain in its original form.[18] Even if apoaequorin did survive digestion intact, its large molecular size and poor fat solubility would prevent it from crossing the blood-brain barrier and, contrary to Quincy’s claim, replace vital proteins in the brain and thus preserve memory.[19]

The Madison Memory Study

From December 2009 to April 2011, Quincy performed an in-house randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on Prevagen. Called the “Madison Memory Study,” Quincy has relied on it to support Prevagen’s advertising claims of memory improvement and other cognitive benefits in users over a 90-day period. During the clinical trial, 218 total participants between the ages of 40 and 91 received either one 10 milligram capsule daily of apoaequorin (treatment group, n=145) or placebo (control group, n=73), with 211 finishing the trial. The study does not state if this sample size had sufficient statistical power to detect clinically meaningful effect sizes a priori in the treatment versus control group. Using nine quantitative, computerized cognitive tests from the Cogstate Brief BatteryTM, Quincy administered the tests to the participants in each group at intervals of 8, 30, 60, and 90 days to measure verbal learning, memory, executive function, psychomotor function, and visual learning. Quincy acknowledged in the study’s synopsis that no statistically significant results were observed in the treatment group over the entire study population on any of the nine cognitive tasks.[20]

After Quincy failed to find a treatment effect for the study population as a whole, its researchers conducted more than 30 unplanned post hoc subgroup analyses of the results,[21] looking at data broken down by several variations of small subgroups for each of the nine cognitive tasks. This is a classic example of data dredging or “p-hacking,” where researchers perform unplanned analysis following rejection of an overall null hypothesis with the goal of finding significant effects wherever and however they can be found.[22] If one conservatively assumes 31 subgroups from the “more than 30” subgroup range, the probability of finding at least one false positive at the 0.05 level of statistical significance (“alpha”) is the family-wise error rate (FWER) = p = 1 – (1-0.05)31 = 0.796 = 80%. An 80% probability of finding at least one false positive in an unplanned post hoc subgroup analysis provides compelling evidence of a deficiency in the study’s methodology. As such, post hoc subgroup analysis is suitable only for generating new hypotheses for future studies; thus, it is inappropriate for generating definitive results and establishing Prevagen’s efficacy in the Madison Memory Study.[23]

After performing the post hoc subgroup analysis, Quincy found two overlapping subgroups from the 30-plus subgroups examined, AD8 0-1 and AD8 0-2, having low to mild initial impairment scores. AD8 refers to an eight-question self-rating screening tool having a possible score ranging from 0 to 8.[24] The effect sizes in these subgroups had modest levels of statistical significance with p-values ranging from 0.01 to 0.04 (assuming an alpha of 0.05) in three of the nine cognitive tasks.[25] Given the 80% minimum Type I error rate previously calculated for 30-plus comparisons, these statistically significant findings are very likely false positives and not reliable evidence of a treatment effect.

The final and decisive shortcoming of Quincy’s subgroup analysis was its failure to use multiple testing procedures to control for the family-wise error rate (FWER).[26] These procedures include the Bonferroni correction and Benjamini-Hochberg (B-H) methods and are well known in statistical practice. For statistical significance, Bonferroni requires that all subgroup p-values be less than alpha divided by the number of subgroups, or 0.05/31 = 0.0016; B-H doubles that threshold for a second subgroup. Compared to the Bonferroni and B-H criteria, the results for subgroups AD8 0-1 and 0-2 are in fact not statistically significant; therefore, Prevagen’s efficacy cannot be proved both in the study subgroups and in the entire study population.

Litigation

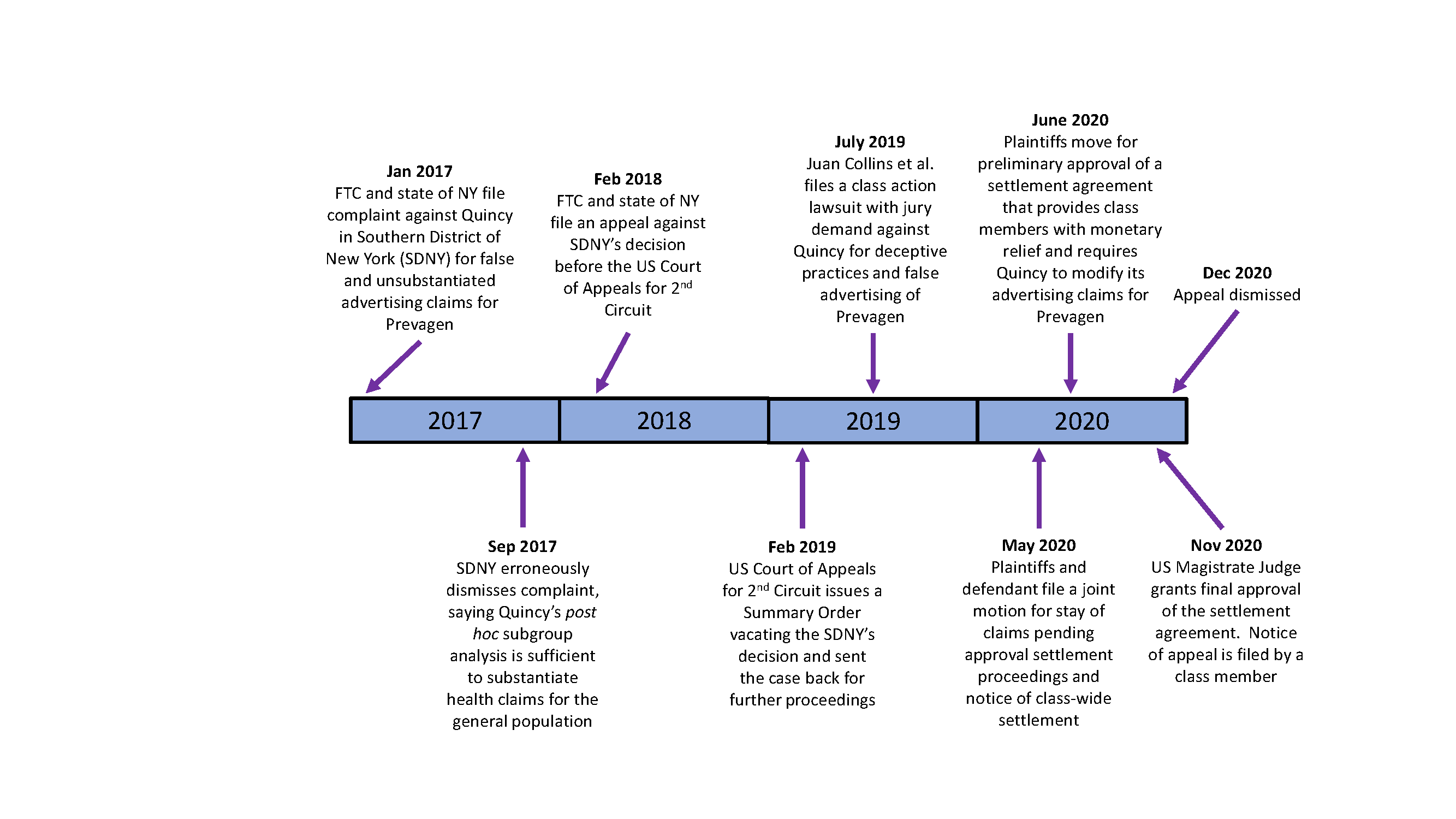

In response to Quincy’s claim that the Madison Memory Study proved that Prevagen provided cognitive benefits and was “clinically shown” to work, the FTC and New York State’s Attorney General filed a consumer protection complaint on January 9, 2017 against Quincy charging the company with making false and unsubstantiated claims.[27] The complaint experienced a turbulent four years in and out of court; see Figure 1 below for a summary timeline. Plaintiffs moved in June 2020 for a class settlement that provided purchasers with a small cash refund of Prevagen suggested retail price, with awards ranging from $12 to $70 per class member.[28] Quincy also agreed to stop advertising that Prevagen improves memory without providing adequate scientific evidence to support the claims, or without qualifying them with a court-approved disclaimer. Post-settlement, in lieu of providing reliable data, Quincy chose to use the approved disclaimer, “Based on a clinical study of subgroups of individuals who were cognitively normal or mildly impaired. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

Figure 1. Litigation Timeline[29]

Recommendations

The Prevagen lawsuit and settlement agreement provides compelling evidence that dietary supplement regulations are in urgent need of revision to reduce the risk to public health attributable to dietary supplement health advertising unsubstantiated by strong science. Using Section 8 New Dietary Ingredients in DSHEA as a template, proposed wording for this revision is shown below in boldface type for appending to Section 6 Statements of Nutritional Support, paragraph (B) of 21 U.S.C. § 343(r)(6)[30]:

“(B) the manufacturer of the dietary supplement has substantiation that such statement is truthful and not misleading, MEETS A STRONG STANDARD OF SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE APPROPRIATE FOR THE BENEFIT BEING CLAIMED, AND IS SUBMITTED TO THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION FOR REVIEW AND APPROVAL AT LEAST 75 DAYS BEFORE THE DIETARY SUPPLEMENT IS INTRODUCED OR DELIVERED FOR INTRODUCTION INTO INTERSTATE COMMERCE. . . .”

This revision would render “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration . . .” within Section 6, paragraph (C) obsolete and require its removal from 21 U.S.C. § 343(r)(6).

FDA should use its “significant scientific agreement standard” (SSA) to evaluate the truthfulness of dietary supplement manufacturer statements. The SSA requires “agreement among qualified experts that the claim is supported by the totality of publicly available scientific evidence . . . .”[31] This is much stronger than the current “competent and reliable scientific evidence” standard used by Quincy for substantiating Prevagen’s structure/function claims.[32]

To assist FDA in becoming a proactive dietary supplements regulator, its premarket approval role can be funded using a new user fee program patterned after the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992.[33] FDA should structure the user fee like a non-negotiable tax, similar to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registration fee system.[34] Using the SEC and its fee system as a model, an arm’s-length relationship (versus a potential captive one) would help prevent the dietary supplement industry from having the power to set goals and expectations and influence FDA’s preapproval decision-making.

Lessons from Prevagen

The Quincy v. FTC case is current, timely, and provides an example of the critical intersection between dietary supplements, public health law, and epidemiology. The case demonstrates that public health law is informed by clinical study results and epidemiological principles used to analyzed and interpret those results. Deceptive marketing of products like Prevagen can adversely affect public health because individuals suffering from memory loss and other cognitive decline may decide to use this product or similar dietary supplements in lieu of seeking proper medical care. Using the average-patient standard, FDA does not approve drugs based on post hoc subgroup analysis if they do not benefit the average patient,[35] and it should require dietary supplement marketing claims be held to the same standard.

As a remedy to dietary supplement industry’s deceptive marketing practices, FDA should transition from a reactive to a proactive posture to prevent future unfair and false dietary supplement advertising. Accordingly, preapproval of data provided to substantiate structure/function and other nutritional support claims on dietary supplement labeling should be required before the product goes to market. Ultimately, dietary supplement consumers should make purchase decisions based on compelling science and not on unverified or unverifiable marketing claims.

[1] Long, J. FDA supplements chief identifies ‘regulatory gap’. Natural Products Insider 2020 September 17, 2020 [cited 2021 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://www.naturalproductsinsider.com/sports-nutrition/supplyside-stories-episode-28-sustainability-commitments-tsi-group-bio-active.

[2] Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Public Law 103-417. 1994 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/about/dshea_wording.aspx.

[3] Racies v. Quincy Bioscience, LLC. Class Action Complaint, Case 3:15-cv-00292-JCS. United States District Court, Northern District of California January 21, 2015; FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017; Collins v. Quincy Bioscience, LLC Class Action Complaint, Case No. 1:19-cv-22864 United States District Court, Southern District of Florida, Miami Division July 11, 2019.

[4] Warning Letter to Quincy Bioscience Manufacturing Inc. 2012 October 16, 2012 July 9, 2021]; Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170723020605/https://www.fda.gov/ICECI/EnforcementActions/WarningLetters/2012/ucm324557.htm.

[5] Racies v. Quincy Bioscience, LLC. Class Action Complaint, Case 3:15-cv-00292-JCS. United States District Court, Northern District of California January 21, 2015; Collins v. Quincy Bioscience, LLC Class Action Complaint, Case No. 1:19-cv-22864 United States District Court, Southern District of Florida, Miami Division July 11, 2019.

[6] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017.

[7] Dietary Supplements – Global Market Trajectory & Analytics.

[8] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017.

[9] Gayle Nicholas Scott, Does Prevagen Help Memory Loss?, Medscape (Mar. 18. 2016).

[10] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017; Bellamy, J. Prevagen goes P-hacking. 2018 June 21, 2018 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/prevagen-goes-p-hacking/.

[11] Frati, P., et al., Smart drugs and synthetic androgens for cognitive and physical enhancement: revolving doors of cosmetic neurology. Curr Neuropharmacol, 2015. 13(1): p. 5-11.

[12] About Prevagen. 2021 2021 March 24,2021]; Available from: https://www.prevagen.com/about-prevagen/.

[13] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.; Gayle Nicholas Scott, Does Prevagen Help Memory Loss?, Medscape (Mar. 18. 2016).

[17] Bauter, M.R. and O. Mendes, Subchronic toxicity of lyophilized apoaequorin protein powder in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicology Research and Application, 2018. 2: p. 2397847318756905.

[18] Bellamy, J. Prevagen goes P-hacking. 2018 June 21, 2018 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/prevagen-goes-p-hacking/; Eisen, M., Clear-cut fraud? Quincy Bioscience faces a potentially ruinous lawsuit over memory claims, in Isthmus. 2017, Isthmus Community Media, Inc: Madison, WI.

[19] Gayle Nicholas Scott, Does Prevagen Help Memory Loss?, Medscape (Mar. 18. 2016); Pardridge, W.M., Targeted delivery of protein and gene medicines through the blood-brain barrier. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2015. 97(4): p. 347-61.

[20] Lerner, K.C., Madison Memory Study: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Apoaequorin in Community-Dwelling, Older Adults. 2016, Quincy Bioscience, LLC.

[21] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017.

[22] Head, M.L., et al., The extent and consequences of p-hacking in science. PLoS Biol, 2015. 13(3): p. e1002106; Schulz, K.F. and D.A. Grimes, Multiplicity in randomised trials II: subgroup and interim analyses. Lancet, 2005. 365(9471): p. 1657-61.

[23] Federal Trade Commission, et al. v Quincy Bioscience Holding Co., et al., Motion of Public Citizen, Inc. Center for Science in the Public Interest, and the Collaboration for Research Integrity and Transparency for Leave to File Amicus Brief in Support of Plaintiffs – Appellants and Reversal, Case 17-3745. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit March 6, 2018; FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company, Brief of the Federal Trade Commission, Case Nos. 17-3745 & 17-3791 United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, March 5, 2018; Wallach, J.D., et al., Evaluation of Evidence of Statistical Support and Corroboration of Subgroup Claims in Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern Med, 2017. 177(4): p. 554-560.

[24] Lerner, K.C., Madison Memory Study: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Apoaequorin in Community-Dwelling, Older Adults. 2016, Quincy Bioscience, LLC; Galvin, J.E., et al., Patient’s rating of cognitive ability: using the AD8, a brief informant interview, as a self-rating tool to detect dementia. Arch Neurol, 2007. 64(5): p. 725-30.

[25] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017; Bellamy, J. Prevagen goes P-hacking. 2018 June 21, 2018 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/prevagen-goes-p-hacking/; Lerner, K.C., Madison Memory Study: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Apoaequorin in Community-Dwelling, Older Adults. 2016, Quincy Bioscience, LLC.

[26] Motulsky, H., Intuitive Biostatistics – A Nonmathematical Guide to Statistical Thinking. Fourth ed. 2018: Oxford University Press.

[27] FTC and The People of the State of New York v. Quincy Bioscience Holding Company and others. Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Other Equitable Relief, Case No. 1:17-cv-00124. United States District Court, Southern District of New York, January 9, 2017.

[28] Collins v. Quincy Bioscience, LLC, Settlement Agreement and Release, Case No. 1:19-cv-22864 United States District Court, Southern District of Florida, Miami Division June 24, 2020.

[29] Class-Action Tracker: Quincy Bioscience’s Prevagen. March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://www.truthinadvertising.org/quincy-biosciences-prevagen/.

[30] Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Public Law 103-417. 1994 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://ods.od.nih.gov/about/dshea_wording.aspx.

[31] Authorized Health Claims that Meet the Significant Scientific Agreement (SSA) Standard. January 12, 2018 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/authorized-health-claims-meet-significant-scientific-agreement-ssa-standard.

[32] Guidance for Industry: Substantiation for Dietary Supplement Claims Made Under Section 403(r) (6) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. 2009 September 20, 2018 March 24, 2021]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-substantiation-dietary-supplement-claims-made-under-section-403r-6-federal-food.

[33] PDUFA VI: Fiscal Years 2018-2022. 2017 July 7, 2020 July 8, 2021]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/industry/prescription-drug-user-fee-amendments/pdufa-vi-fiscal-years-2018-2022.

[34] Order Making Fiscal Year 2017 Annual Adjustments to Registration Fee Rates. 2016, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission; Hilzenrath, D.S. FDA Depends on Industry Funding; Money Comes with “Strings Attached”.

[35] VanDerLaan, M., A. Malani, and O. VanDerBembom, Accounting for Differences among Patients in the FDA Approval Process. (University of Chicago Public Law & Legal Theory Working Paper No. 281, 2009).

Update Magazine

Winter 2021

LEILA BARRAZA is an associate professor in the Department of Community, Environment & Policy at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health. She is the Director of the Arizona Area Health Education Centers (AzAHEC) program. She also serves as a senior consultant with the Network for Public Health Law—Western Region Office.

LEILA BARRAZA is an associate professor in the Department of Community, Environment & Policy at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health. She is the Director of the Arizona Area Health Education Centers (AzAHEC) program. She also serves as a senior consultant with the Network for Public Health Law—Western Region Office.

YANN KLIMENTIDIS is an associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

YANN KLIMENTIDIS is an associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health. ELIZABETH JACOBS is a cancer and nutritional epidemiologist and professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Nutritional Sciences at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health and the University of Arizona Cancer Center.

ELIZABETH JACOBS is a cancer and nutritional epidemiologist and professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics and Nutritional Sciences at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health and the University of Arizona Cancer Center.